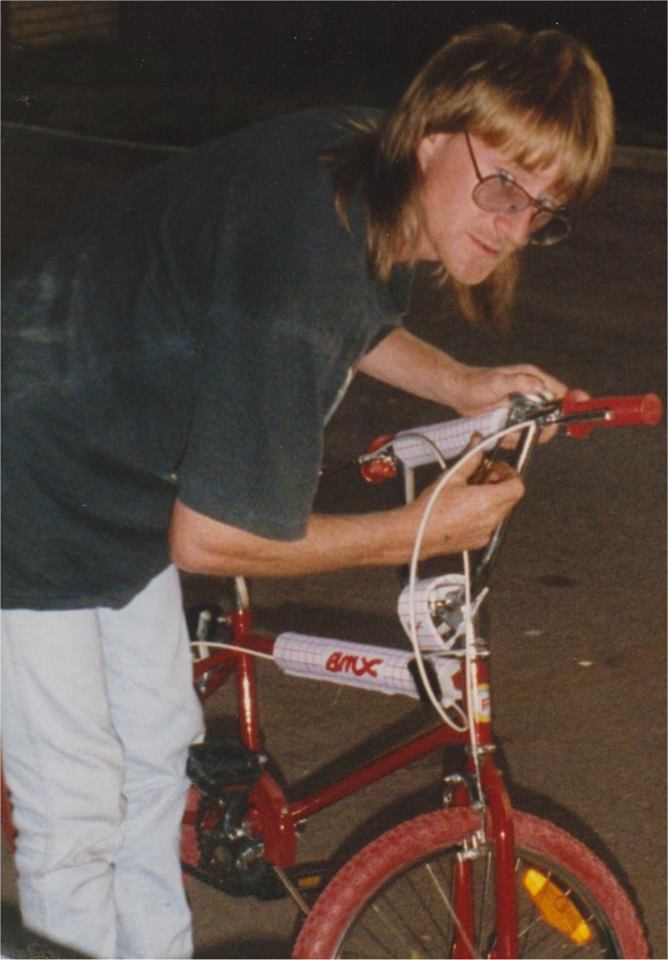

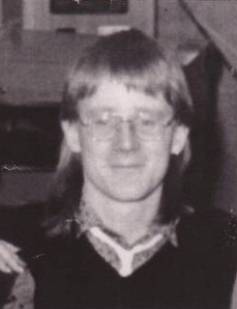

Tyrone Macqueen was 25-years-old when he went missing. He was

last seen at his home address in Warring Street, Ravenswood in

Northern Tasmania at about 8pm on Friday 1 July 1994.

Enquiries suggest that later that evening, he may have attended

a party in bushland surrounding Ravenswood.

There have been no confirmed sightings of Tyrone since this

time. Despite extensive enquiries by police his whereabouts

remain unknown

If you have information that may assist police to locate Tyrone,

please call Crime Stoppers on 1800 333 000.

MAGISTRATES COURT of TASMANIA CORONIAL DIVISION

Record of Investigation into Death (Without Inquest)

Coroners Act 1995 Coroners Rules 2006 Rule 11

I, Simon Cooper, Coroner, having investigated the suspected death of Tyrone Frederick MacQueen make the following findings.

Introduction

1. Tyrone Frederick MacQueen was the son of Grace and Raymond MacQueen. He was born in Hobart on 26 December 1968, one of eight children of his parents. Mr and Mrs MacQueen separated in about 1979. At the time of his disappearance in July 1994 Mr MacQueen was living with his mother and his niece, Rachel Joy Anstey, at 2/97 Warring Street, Ravenswood in Tasmania. He was single, never having married, and unemployed. Both his parents are now dead, having both died in 2000.

2. Mr MacQueen has not been seen or heard of since the evening of Friday, 1 July 1994. He was reported as a missing person to Tasmania Police on 3 July 1994 by his mother.

3. The investigation of deaths in Tasmania is governed by the Coroners Act 1995. Section 21(1) of the Act provides that “[a] coroner has jurisdiction to investigate a death if it appears to the coroner that the death is or may be a reportable death.”

4. ‘Death’ is defined in section 3 of the Act as including a suspected death.

5. ‘Reportable death’ is defined in the same section as meaning, inter alia, a death which occurred in Tasmania and was unexpected or the cause of which is unknown.

6. Thus if a coroner suspects (on reasonable grounds) that a person has died and the death meets the definition of a reportable death, then the coroner has jurisdiction to investigate.

7. For reasons which will become apparent in this finding I am satisfied that jurisdiction exists to investigate the disappearance of Mr MacQueen.

Mr MacQueen’s Background

8. Born in Hobart but raised in Launceston, Mr MacQueen was one of eight children of his parents. He seems to have had a normal upbringing but was greatly affected by the death of his brother, Scott, in 1982. Scott MacQueen, aged just 12, died when he was hit by a car.

9. Scott alighted from a stationary MTT bus to change a $2.00 note (the driver seemingly having insufficient change and telling him to get change from a shop across the road from the bus stop). Scott moved from the front of the bus into the path of a truck, which struck him. He died later the same day from the injuries he sustained. The original inquest file relating to Scott’s death does not make it clear whether Mr MacQueen was present and actually witnessed his brother being struck by the truck, but an affidavit made by Mrs MacQueen shortly after Mr MacQueen’s disappearance tells a different story.

10. In that affidavit Mrs MacQueen says Tyrone, who was only about 14 years of age at the time, was present and saw his brother run over. It is very clear that Mr MacQueen was greatly affected by his younger brother’s death.

11. On 31 July 1992 Tyrone was first seen as a patient by Mental Health Services North. He was admitted to the hospital as a result of a referral by his General Practitioner. A report provided by the Department of Health and Human Services in April 2009 stated that Mr MacQueen was said at admission to be in an acutely psychotic state. He was described as incoherent with some grandiose delusions. He reportedly responded to treatment and was discharged on 6 August 1992. However, following his discharge from hospital Mr MacQueen failed to continue with follow-up appointments.

12. Six days later he was re-admitted as an involuntary patient under an order made under the Mental Health Act. Again, his behaviour was reportedly bizarre, his speech incoherent, he was confused and refusing to comply with treatment. He was not discharged until 15 September 1992. After his discharge from hospital he was followed up at the hospital’s outpatients clinic regularly. The report from the Department of Health and Human Services indicates that his ongoing recovery was slow with minor relapses complicated by partial compliance with this treatment and further complicated by the excessive consumption of alcohol.

13. Mr MacQueen travelled to Western Australia in November 1993. Significantly, in the context of this finding, it would seem he went missing in that state for three or four days. He eventually contacted his mother and it was arranged that he would go to hospital. He did so and was hospitalised for a month as a psychiatric inpatient at the Grey Lynn’s Hospital in Perth, from which he was discharged (when he was well enough to travel) on 6 March 1994 following a two week stay.

14. He immediately returned to Tasmania and shortly after his return he was admitted to the psychiatric unit at the Launceston General Hospital, on 21 March 1994. He was in an acutely psychotic state. After three weeks in the hospital he was considered well enough for discharge and was discharged on 12 April 1994.

15. Mr MacQueen moved back in with his mother in a unit at 2/97 Warring Street, Ravenswood. He was living there at the time of his disappearance six months later. After his discharge from the psychiatric unit at the Launceston General Hospital, and before his disappearance, he was followed up at the outpatients clinic. Once again he was non-compliant with his medication and did not always attend his appointments. He was last seen at the outpatients clinic on 3 June 1994. He was due for follow-up on 30 June 1994 but did not attend that appointment.

16. The report from the Department of Health and Human Services confirms that Mr MacQueen had a diagnosis of chronic schizophrenia. A differential diagnosis was drug-induced psychosis. A major impediment to his successful treatment was his poor compliance with treatment and also a strong suspicion of the excessive use of both illicit drugs and alcohol.

Circumstances of Disappearance

17. According to his mother’s affidavit, after his return home in late January 1994 he constantly displayed signs of depression. She reports him saying words to the effect of “I shouldn’t be here, I would be better off dead”. Her son seems to have dwelt constantly on the circumstances of his brother Scott’s death and blamed himself for it.

18. Shortly after his return home to his mother’s unit at 2/97 Warring Street, Ravenswood, Mrs MacQueen took her son to the Launceston General Hospital where he was admitted as an inpatient for psychiatric treatment for another month or so. Mrs MacQueen also recounts her son going away without telling her where he was going or where he was for two or three days at a time. The missing person report completed at the time of his disappearance records similar information.

19. At the time of his disappearance he was described as appearing very depressed and “down”. He was prescribed medication but apparently non-compliant, including anti-depressants and tablets to deal with blood pressure.

20. In the immediate lead up to his disappearance, his behaviour, according to his mother’s affidavit, became extremely problematic. He demonstrated upset and depression and reportedly constantly talked about suicide. On the evening of Tuesday, 28 June 1994 he cut his wrist in his bedroom. He stayed home all day Wednesday and Thursday, rarely leaving his bedroom and rocking back and forwards and listening to the radio.

21. His behaviour seems to have worsened as a result of a failed overture to a young woman in the area of his home. In the afternoon of Tuesday, 28 June 1994, his cousin, Ms Donna Venn, received flowers and a card, twice a few hours apart, from Mr MacQueen. Ms Venn and Mr MacQueen seem to have had a close friendship, in the sense that Mr MacQueen would sit for long periods of time talking to Ms Venn, who would, she said, listen and attempt to calm him. Mr MacQueen possibly became infatuated with Ms Venn, although she says he never acted inappropriately towards her, or made any sexual advances.

22. As has already been mentioned Ms Rachel Anstey, Mr MacQueen’s 12 year old niece, was living in the unit with her grandmother and uncle. Ms Anstey made an affidavit in 2009 about her uncle’s disappearance. Like Ms Venn, she described herself as also having a close relationship with Mr MacQueen, describing him as her favourite uncle and someone with whom she used to talk to a lot. She said not long before her uncle disappeared that she and he had discussed a “girl he really liked” and that her uncle had asked her what he should give the girl to let her know that he liked her. Ms Anstey said that her uncle told her she knew the object of his affection, but would not tell her who it was.

23. Ms Anstey said in her affidavit:

“[a]bout 4.00 pm on Thursday, 30 June 1994, I remember getting home to Nan’s place, after being at school. I shared a bedroom with Nan and when I went into the bedroom I saw some flowers hidden under Nan’s bed. With the flowers was a brand-new Celine Dion audio cassette tape, still in its packaging. There was a card with the flowers which read ‘To Jody’. I can’t remember if the card said it was from a secret admirer or named Tyrone. Because of my previous discussions with Tyrone, about the girl he liked, I believed he had sent or given flowers and a cassette tape to Jody. I believed Jody to be Jody Venn (Donna Venn) because that was the only Jody that I knew. I guessed Tyrone would not tell me because we related to her”.

24. It seems clear enough that ‘Jody’ is the woman also known as Donna Venn. It would also seem that the flowers and cassette may have been a gift to her either not sent or, if sent, then returned. Broadly speaking, although slightly different in detail, Ms Anstey’s account supports Ms Venn’s – and lends credence to the suggestion that Mr MacQueen had, in the immediate lead up to his disappearance, suffered a romantic setback. Mr MacQueen was described by his niece as on that evening seeming “a bit quiet, but reasonably normal”. That evening uncle and niece made plans to go to a school rock eisteddfod the next night, Friday, 1 July 1994. Mr MacQueen said he would accompany his niece.

25. Ms Anstey’s affidavit then goes on to outline the circumstances in the immediate lead up to her uncle’s disappearance. She described her uncle on the afternoon of Friday, 1 July 1994 (after she returned home from school) as “acting very strange”. She said she had been looking forward to her uncle going to the eisteddfod with her but he told her he did not want to go and that he “just wanted to stay home and not go anywhere”. He explained he did not feel like going anywhere. Ms Anstey then left at about 8.00 pm to go to the eisteddfod at Queechy High School.

26. It would appear that Ms Anstey was the last person to certainly see Mr MacQueen alive. She described her uncle as giving her a cuddle in the lounge room and wishing her luck. She said she thought he was dressed in a flannelette shirt and blue jeans but could not remember the colour of his shirt. She left her uncle alone; her grandmother not being home.

27. Ms Anstey got home from the eisteddfod between 11.00 pm and 11.30 pm. She said no one was home and that there was no note from anybody. Fifteen years later when she made her affidavit she could not remember if the house was locked or not when she got home. She said her grandmother got home fifteen minutes or so after she did. Her grandmother asked her where Mr MacQueen was an Ms Anstey told her she did not know. Grandmother and granddaughter then went to bed; Mrs MacQueen sleeping in her bedroom and Ms Anstey sleeping in the lounge room.

28. In her affidavit Ms Anstey confirms knowing that her uncle suffered from schizophrenia, although she was unaware when he was diagnosed. She was aware he was prescribed medication for the condition but did not like taking it and was frequently non-compliant. Ms Anstey also confirmed that at times when she believed he had not taken his medication that her uncle told her he blamed himself for his brother Scott’s death.

29. The next morning Mr MacQueen was not home. Mrs MacQueen rang a couple of friends of his in an effort to locate him but had no success. According to Ms Anstey’s affidavit Mrs MacQueen reported her son’s disappearance to the police more or less straight away.

30. The original Tasmania Police Missing Person Report is dated 3.00 am on 3 July 1994. It deals with the circumstances of Mr MacQueen’s disappearance. In it he is described as being 25 years of age with brown/blonde short hair, blue eyes, fair complexion, slim build and approximately 175 cm in height.

31. The report makes mention of the schizophrenia and the possibility that he is both suicidal and had not been taking his medication. Additionally, the report records that Mr MacQueen had taken his mother’s medication. Mrs MacQueen’s affidavit indicates that after she noticed her son was missing she discovered that her prescription medication was also missing from a cosmetic bag in her bedroom. She found that in particular the following tablets were missing: Suromtil 50mg (an antidepressant) - 100 tablets; Tonormin (blood pressure medication) - 28 tablets; Panadeine (a painkiller) - 15 tablets; Stemetil (typically used for the treatment of vertigo and nausea) 5 mg - 20 tablets; and Estigyn (a hormone treatment) 20 mg - 50 tablets.

The initial search for Mr MacQueen

32. Police commenced a missing person enquiry in relation to Mr MacQueen’s disappearance immediately. Enquiries were conducted with friends of Mr MacQueen as well as checks at hospitals in both the North and South of the state along with areas where Mr MacQueen was known to frequent. All of these enquiries were uniformly unsuccessful.

33. A search was conducted of bush land in the vicinity of the unit at Warring Street, Ravenswood. Statements were taken from members of Mr MacQueen’s family. Mr MacQueen’s psychiatrist, Dr Joel, was spoken to and medical records interrogated as well as inquiries conducted with Mr MacQueen’s bank. This line of enquiry revealed that his account had last been used on 28 June 1994. Checks were conducted with all airlines, the Bass Strait ferry and Redline coaches. None yielded any information that was of any assistance in locating Mr MacQueen.

34. The searches of the bushland continued over a two-day period. Apart from extensive and careful land searches, dams in the area were dragged. No sign of Mr MacQueen was found.

35. The fact of Mr MacQueen’s disappearance was widely reported in the media. As a consequence several people came forward suggesting that they had seen Mr MacQueen. Each of those “sightings” was extensively examined and it is apparent, and I am satisfied, that each was mistaken and that none of the reported sightings of Mr MacQueen were of him.

36. The searches of the geographical area surrounding the unit continued. Some keys and a cigarette packet were located near the Launceston tip. A witness identified that they belonged to Mr MacQueen. The items were forensically tested but the testing did not advance the search for Mr MacQueen.

37. Mr MacQueen appeared to have disappeared without a trace. There is no evidence that anyone has seen or heard from him since about 8.00 pm on Friday, 1 July 1994. All of the evidence satisfies me that he is dead. His bank account has not been accessed since he disappeared. He has not claimed social security benefits (which was his sole source of income) since his disappearance. Extensive enquiries carried out by Tasmania Police State Intelligence Services show that apart from a single account Trust Bank (a now-defunct financial entity) he had no accounts with any other banks or financial institutions. Since his death there has been no record of him having accounts with any energy providers, having held a drivers licence, been on an electoral roll, or left Australia. He is not recorded with any of the police agencies in any of the other states or territories of the country. In all of the circumstances, on all of the evidence, I am satisfied to the requisite legal standard that Mr Tyrone Frederick MacQueen is dead.

38. Having excluded the possibility that Mr MacQueen is still alive it seems clear enough that the possibilities are that he died as the result of an accident, or suicide, or at the hand of another or others. The legal questions that then remain are whether it is possible to determine the circumstances, cause and where and when he died - questions posed by section 28(1) of the Act. I turn to consider those questions.

Accidental Death?

39. Although the possibility that Mr MacQueen died as the result of some type of accidental death needs to be considered, the fact that his body has never been found does not allow for the matter to be either excluded or determined to have been the cause of Mr MacQueen’s death.

Suicide?

40. Mr MacQueen reportedly expressed suicidal ideation in the lead up to his disappearance. He also appears to have taken with him a number of drugs belonging to his mother. Evidence unearthed as part of the investigation suggests that he had suffered a romantic setback in the days leading up to his disappearance, had taken to his room and possibly self-harmed. He had a welldocumented history of schizophrenia. Each of these factors individually certainly point in the direction of suicide as a likely cause of his death. Collectively they may be thought to strengthen an argument in favour of suicide as a cause of death.

41. Balanced against that though is the fact that Mr MacQueen had on a number of occasions in the past disappeared for two or three days at a time, but had always returned. Similarly, no note or letter written by Mr MacQueen convincing any suicidal intent seems to have been found as part of the police investigation or by a member of his family in the aftermath of his death.

42. Before a coroner can make a finding of suicide it is necessary to determine the cause of death (whether that be asphyxia by hanging or intoxication by drugs and the like) and be satisfied on the basis of evidentiary material that when the act which caused a person’s death was undertaken it was done voluntarily and with the express intention of ending that person’s life.

43. In this case given the absence of any evidence whatsoever that could satisfy me as to either of the factors which go to make up a suicide, I cannot be satisfied that Mr MacQueen’s death was suicide.

Homicide?

44. The possibility that Mr MacQueen was the victim of foul play must also be considered. In the years that followed his disappearance, as his death continued to be investigated, numerous theories and rumours were advanced to account for Mr MacQueen’s disappearance and presumed death. The rumours and theories are just that; none seem to have a basis in fact.

45. The first rumour suggesting Mr MacQueen was the victim of foul play was received by police on 16 July 1994. An aunt of Mr MacQueen’s, Ms Jeanette Baker, provided this third-hand information to police. The substance of that information was that Mr MacQueen had on the evening of his disappearance been at a party in the bush at the rear of the suburb of Ravenswood. It was said that the party involved alcohol and drugs and that in some way it had gotten out of hand. It was said that Mr MacQueen had been for some reason stabbed by someone and buried somewhere nearby. The bushland area referred to had already been searched by police. Nothing was located which suggested Mr MacQueen had been the victim of foul play in that area and buried there. No grave was located. No human remains were found. No one was located by police that was at the party at which Mr MacQueen was supposedly stabbed. No witness was able to be located which could assist in advancing that matter any further.

46. The allegation regarding the party in the bush somewhere in the back of Ravenswood was re-investigated in April 2009. The original informant was spoken to. She provided police with additional information all of which was investigated and none of which appeared to have any basis in fact, or if it did, was unable to be verified in any way.

47. Anonymous information was received via a police hotline in August 2005. That information was a variation on the party in the bush theory. It suggested that on the night of Mr MacQueen’s disappearance he arrived at that party (this time at the end of Bendigo Street rather than Warring Street) with a “handful of serepax tablets”). One of the persons present at the party asked for the tablets and when Mr MacQueen refused an argument ensued, a fight developed and Mr MacQueen was stabbed to death with a pocketknife and buried under the basement of an address in Ravenswood. The nominated address in Ravenswood was searched. No grave, sign of ground disturbance, human remains, or anything to suggest that Mr MacQueen had been buried under that house or near it was discovered by police.

48. In April 2009 information was received from a member of the public suggesting that Mr MacQueen had been bashed and killed by criminals at Rossarden. The person making the allegation refused to make an affidavit. She described witnessing the bashing to death of a young male by various identified criminals. She went on to describe being ‘made’ clean up with another woman after the killing. It is unnecessary to detail the information provided to police other than to say it is fanciful, riven with inconsistencies, not verified on oath and proved impossible to verify a single detail of it. For example, the other woman named when spoken to by police whilst recalling a bashing gave a description of the victim as wearing black rimmed glasses (which Mr MacQueen did not) and having dark hair (Mr MacQueen’s hair was blonde). She did not know what happened to the young man (which is at odds with the account of the original informant). It proved impossible to identify several of the people said to have been present and presumably witnesses to the bashing.

49. It may be that the information provided was in part true in the sense that it is quite possible that a group of criminals, at some stage, bashed a young man with dark rimmed glasses and dark collar length hair. It is impossible to judge. However, even if it is true (wholly or in part), there is nothing, at all, to suggest that the victim of that bashing and possible homicide described to police was in fact Mr MacQueen.

50. More importantly perhaps is the fact that there is no evidence, at all, establishing any link, at any time, between Mr MacQueen and the town of Rossarden nor anyone who lived there in 1994.

51. In summary, there is no evidence to suggest that Mr MacQueen was the victim of foul play; either at a party in bushland near Ravenswood or at Rossarden or anywhere else. Logically, he is most likely to have died in this state if only because he had no means to transport other than walking, he is not identified as having left the state and the chances of him travelling out of the state to die seem very remote indeed. However, on the available evidence I cannot say how, where, when and in what circumstances Mr MacQueen met his death.

Formal Findings

52. In the circumstances I am unable to answer several of the questions posed by section 28(1) of the Coroners Act 1995.

53. I make the following formal findings: a) The identity of the deceased is Tyrone Frederick MacQueen; b) I am unable to determine the circumstances in which Mr MacQueen died; c) I am unable to determine the cause of Mr MacQueen’s death; and d) Mr MacQueen died in Tasmania on or after 1 July 1994. Comments and Recommendations

54. I extend my appreciation to investigating officer, Detective Senior Constable P.J. Barrett, for his investigation and report.

55. The circumstances of Mr MacQueen’s death are not such as to require me to make any comments pursuant to Section 28 of the Coroners Act 1995. I do however recommend that the file remain open and the subject of continued and ongoing investigation with a view to attempting to find what became of Mr MacQueen.

56. I convey my sincere condolences to the family and loved ones of Mr MacQueen.

Dated 18 October 2018

at Hobart in Tasmania.

Simon Cooper

Coroner