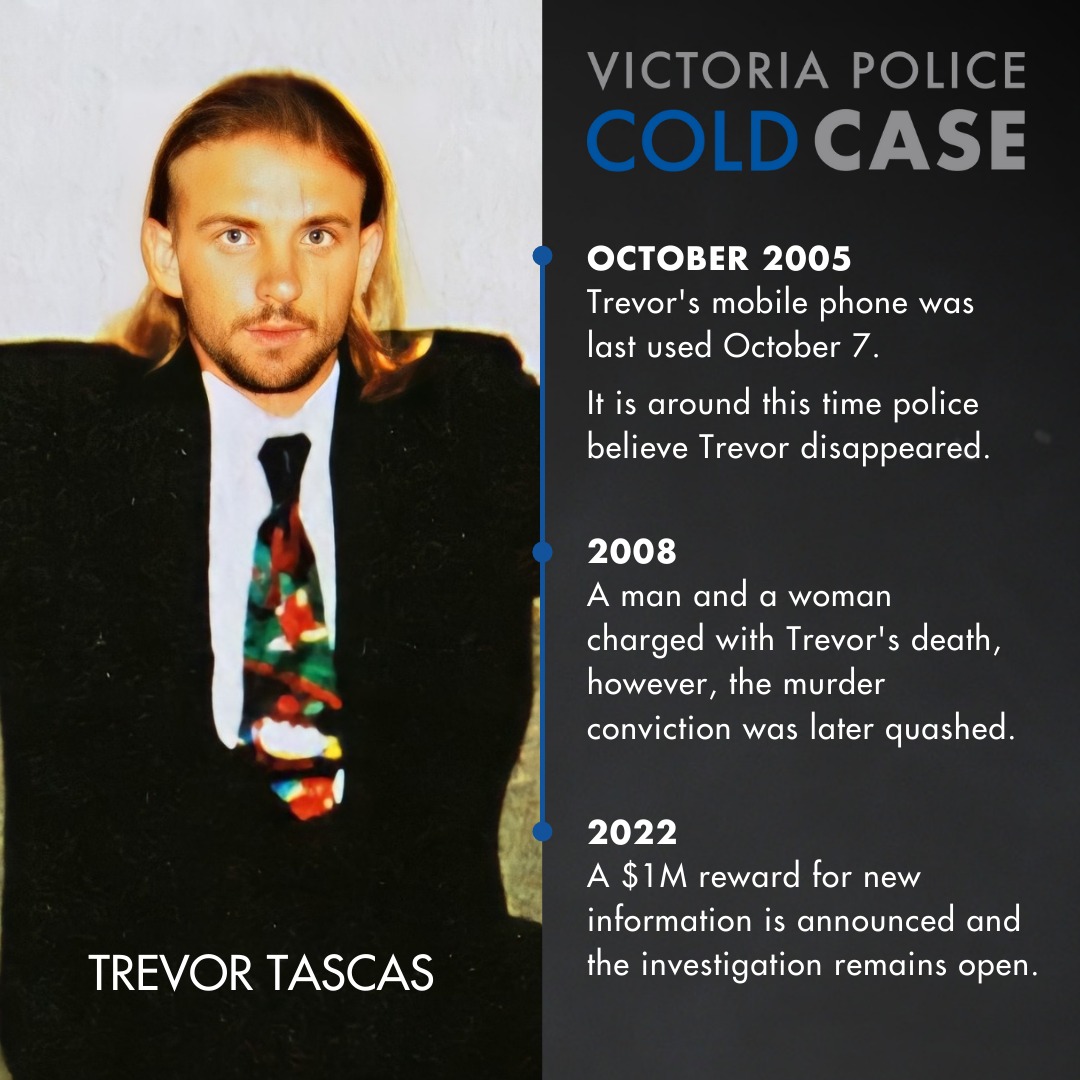

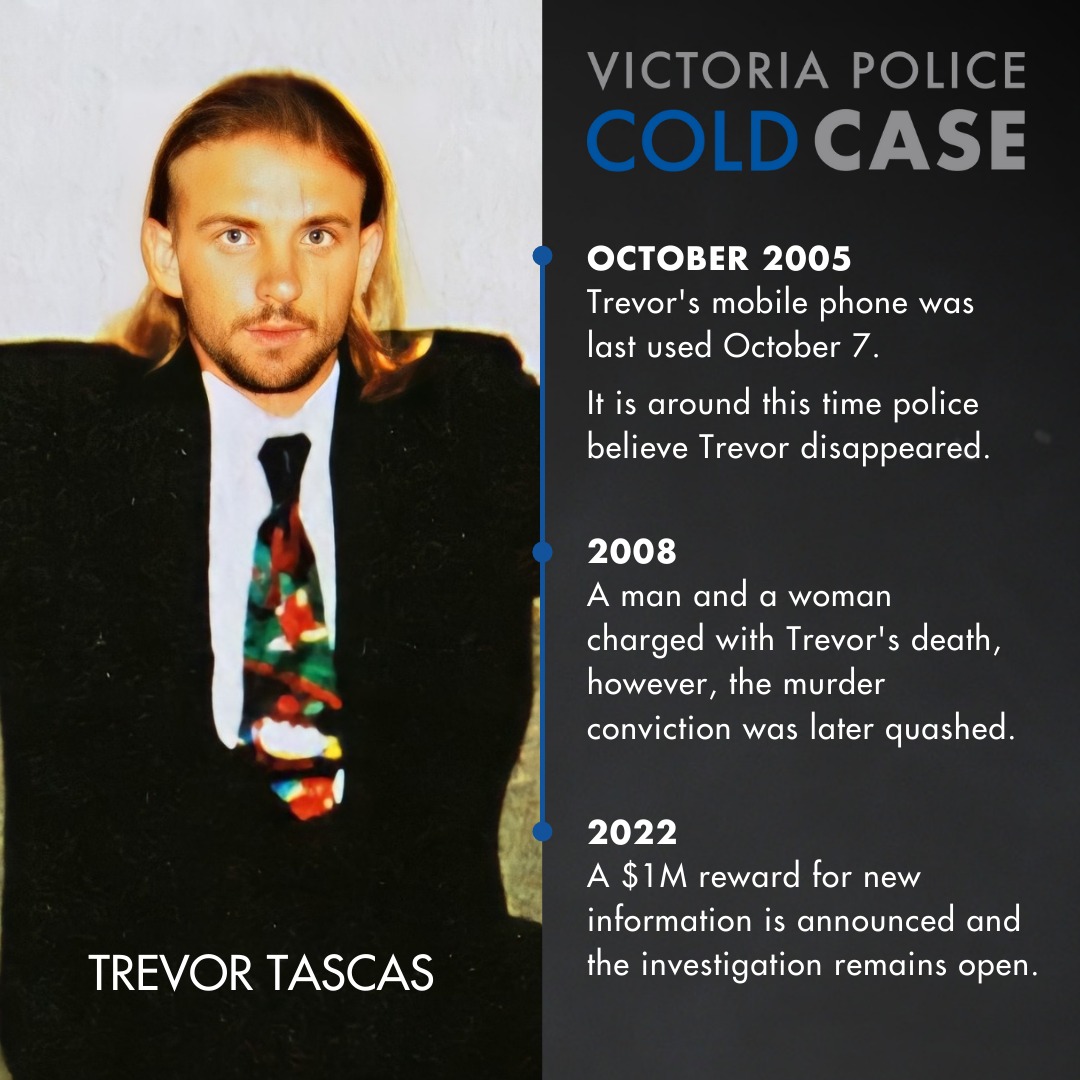

Trevor TASCAS

Trevor TASCAS

|

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF VICTORIA

|

Not Restricted

|

AT GEELONG

CRIMINAL DIVISION

No. 1430 of 2009

|

THE QUEEN

|

|

|

|

|

|

V

|

|

|

|

|

|

LAWRENCE ALEXANDER BUTLER

|

|

---

|

JUDGE:

|

KING J

|

|

WHERE HELD:

|

Geelong

|

|

DATES OF HEARING:

|

29, 30 September, 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8 October – Trial, Plea 30

November 2009

|

|

DATE OF SENTENCE:

|

15 December 2009

|

HER HONOUR:

1 Lawrence Alexander Butler, you have been found guilty of the murder of Trevor

John Tascas at Whittington, between the 5th and 12th day of October 2005. You

pleaded not guilty and a trial was conducted. The matter was adjourned until 30

November 2009, at the request of your counsel, to enable a psychological report

to be prepared.

2 You are currently aged 46 years of age, having been born on 17 October 1963

and your last occupation was as a safety consultant / trainer and you were

residing at No.4 Thatcher Court in Whittington, the scene of the murder.

3 The deceased man, Trevor Tascas, was born in Geelong in January of 1978, the

only son of Pamela Tascas and Joe Van der Weel. He went by the name of both

Trevor Tascas and Trevor Van der Weel.

4 After leaving secondary school in Geelong, he went to Queensland for

approximately a year, before returning back to Victoria and living mainly in the

Geelong region. He began a relationship with a woman, by the name of Nicole

Riley and together, they moved into a residential property at 338 Anakie Road in

Norlane. That was a property owned by Trevor Tascas' uncle, Neil Grayson.

5 The circumstances under which they moved into the premises were, that the

premises were being purchased by Neil Grayson and he was making the repayments

on the mortgage. Trevor Tascas and Nicole Riley were to take over the repayments

and continue to pay off the property, which they did for a while. After a period

of time, Trevor Tascas became unemployed and the relationship with Nicole Riley

broke down and he ceased making repayments on the mortgage.

6 The first that Mr Grayson became aware of this failure to make the repayments

was, when he received notification from the bank that they intended to repossess

the home. After a considerable deal of argument, between the deceased and Mr

Grayson, his uncle reluctantly agreed to pay him a sum of around $30,000, for

him to vacate the premises and allow his uncle to resume occupation of the

premises, which was done ultimately, by his uncle's daughter.

7 It was around August of 2005 that he left those premises in Anakie Road and

moved into premises, occupied by you, at 4 Thatcher Court in Whittington. You

were residing there, in your mother's house, although your mother was not living

there with you at the time.

8 In 2005 you began a relationship with a woman by the name of Jodi Harris, also

known as Jodi Toulmin. Harris was her married name, having married Troy Harris

in approximately March of 2004. That relationship had ended and during 2005 she

commenced the relationship with you. You assisted Trevor Tascas to move into the

premises at Whittington. Other friends of his and Jodi Harris were also present

at the time of the moving.

9 The money paid to Trevor Tascas by his uncle, Neil Grayson, was paid in

different amounts, over the period of time up until his death. Trevor Tascas

moved into Thatcher Court, and at around the same time, he purchased a new motor

vehicle, a 1994 Holden Calais sedan, which was maroon and silver. He purchased

that from a man by the name of Abdul Allouche, and he was very attached to that

vehicle. He was even more attached to his dog, a Jack Russell Cross which went

by the name of "Lulu". Lulu, whilst originally belonging to Nicole Riley, was

constantly in his presence and moved with him to Thatcher Court.

10 The weekend of the 7th, 8th and 9th of October, being the Friday, Saturday

and Sunday in 2005, was the Bathurst weekend and on that weekend, on the

Saturday, Jodi Harris came to visit you. When she came in she was wanting to

have a shower, as she had stayed overnight at friends and had walked around to

your house. She entered the premises and said that she wished to use the shower.

You told her to wait a minute, which she did, but she eventually followed you

down into the bathroom, where she saw, a white hessian type bag, which was in

the shower recess, which you moved into the bath. She noticed that, there was

blood coloured fluid leaking from the base of the bag. There was one white

hessian type bag on the bottom and another had been placed over the top. They

were recycling bags, similar to the ones, later found in your garage. You

initially told Jodi Harris, that a mate had been fishing and the bag was full of

fish.

11 After showering and drying herself, she left the bathroom and walked up the

hallway, towards the bedroom that you shared with her when she was staying over.

12 In doing so, she walked past the bedroom of Trevor Tascas and noticed a

bloodstained sheet, half on and half off his bed. After dressing, she went

outside, out the front. She said, she had become concerned, with what she had

observed. You also came out the front of the premises and you spoke to her. Her

evidence of the conversation she had with you at this time, could be described

as a little vague and hesitant, but she indicated that you had said to her, that

there had been some sort of physical confrontation between you and the deceased

and that it related to his non-payment of rent.

13 The deceased, at that stage, owed you some weeks rent payment. She made a

comment to you along the line of "Is that Trevor in the bag?", to which you

responded, "Well if you think that, you can come and help", or words to that

effect. She then observed you, drag the bag out of the bathroom and into the

yard at the rear of the premises, put the bag into a large barrel, which was in

the backyard on the concrete. The barrel was similar to a 44 gallon barrel, with

rusted parts around the area of the base, with holes in those rusted parts.

14 She initially said, she saw you attempting to light the article in the drum,

by lighting some form of cloth, but later said, that she could not distinctly

remember that occurring. She also noticed, in the area leading out to the back,

a hacksaw that appeared to be bloodstained. She saw some smoke coming out of the

barrel and she left the premises not long after that.

15 A couple of days later, Ms Harris returned to the premises and helped you

empty the material, that was in the barrel into plastic bags. Her part was,

sweeping up fragments of ash and bone, that were around the base of the drum,

that had leaked or fallen out through the rusted holes in the base. She observed

you place, what appeared to be the material in the barrel, ash and bone type

material, into plastic bags. She saw you take the barrel and those plastic bags

and place them into the boot of Trevor Tascas' car, which was still at your

premises. Some of the other plastic bags, containing the ash, had been placed in

the garbage bin at your premises.

16 After the barrel and bags were placed in the boot, you took Ms Harris home

and then continued on, leaving her at her premises. You returned some hours

later and she saw no further evidence of the barrel.

17 Some short time after this had taken place, a matter of a couple of weeks,

you, together with Jodi Harris, drove to Queensland in the vehicle belonging to

Trevor Tascas. On the way to Queensland, near the border, the vehicle broke down

and a man, by the name of Wayne Patterson, came to assist you to get the car

working again. He got the car going and you travelled in that vehicle with Jodi

Harris, following Wayne Patterson to his premises in Queensland. You stayed

there for a matter of a day, or days and when you left, you gave the vehicle to

Wayne Patterson.

18 A matter of some weeks after you left, the vehicle, that you had given to

Wayne Patterson, was involved in a motor car collision and was written off. That

vehicle was the vehicle belonging to Trevor Tascas.

19 Subsequent to this, around July of 2006, Jodi Harris and her ex-husband, made

two withdrawals from the account of Trevor Tascas, in the sum total of,

approximately $11,000. That sum was, the amount that had been paid into Trevor

Tascas' account by way of his pension payments, from the time he was last seen

on 7 October 2005, until the date of the withdrawal, in August of 2006.

20 The dog, Lulu, the very close companion of Trevor Tascas, was given by you,

to a woman by the name of Nicole Donaghy, in late 2005, with you telling her

that Trevor Tascas had gone and would not be coming back, so she could keep the

dog. You also gave away and sold, his furniture.

21 It is clear from telephone records, bank account records, Medicare records

and many other checks made by the police, over the period that Trevor Tascas has

been missing, that Trevor Tascas, has not been sighted or used any service since

7 October 2005, that is, the Friday before the Bathurst weekend. You gave away

his dog, you sold his furniture, you gave away his car and, when interviewed by

police, you told them a number of lies, in relation to what happened to Trevor

Tascas, what happened to his furniture, what happened to his dog, his car, and

similar matters.

22 You did not give evidence in the trial, and the evidence of Jodi Harris

remains uncontradicted, in respect of her observations.

23 In relation to these matters, I am unable to say precisely how you murdered

Trevor Tascas, in that there were no witnesses to the matter. There was no

confession that was given in court and, the body of Trevor Tascas, I am

satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt, was burnt and disposed of, preventing any

forensic testing or examination of his remains.

24 It was submitted by your counsel, that I was not in a position to know

precisely the circumstances in which you murdered Trevor Tascas and I would have

to accept, that this was a murder at the lowest end of the spectrum, as a

result. I do not agree. For a murder to be at the lowest end, of the range of

murders available, there would have to be material that is put forward, that

mitigates the actual murder itself. As an example, the mercy killing of a person

in their nineties, who was but an hour away from death.

25 Equally, it cannot go at the highest end of the scale of murders, because I

am unaware of any particular aggravating circumstances, such as, by way of

example again, the murder of a child in a planned execution.

26 In my view, I must sentence you as though this is a murder, where there are

neither mitigating nor aggravating factors, to the actual killing itself. The

circumstances of the treatment and disposal of the body, post the murder are

matters of aggravation, in terms of penalty.

27 You have no prior convictions, but your counsel has pointed out to me that

you have a subsequent matter, which was the 9th September 2008, at the

Magistrates' Court at Melbourne, for a count of theft, for which you were fined

$250. That offence occurred in the company of Jodi Harris. That has no real

significance and will not have any impact upon the sentence I impose today.

28 In terms of your personal circumstances, you were the fourth child of your

father Victor, who was a widower with three children, prior to marrying your

mother, Louise. Those children range in age from four to ten years older than

you. Two years after your birth, your parents had another daughter, Katrina, who

is your sister.

29 Your father died in 2007 aged 80 years and you did not have a particularly

positive relationship with him. You believed he favoured his older children.

Your two older brothers, Rodney, 53 years of age and, Paul 56, you described as,

bullying you when you were younger.

30 You had a better relationship with your other half sister, Caroline, who is

50. Your sister, Katrina, is a single person and remains close to you.

31 You were educated at Drysdale Primary School and went to Queenscliff

Secondary College before completing your Trade School course at Geelong

Technical School, as a fitter and turner.

32 You had been actively involved with football and the scouts whilst growing up

and although not having a particularly good relationship with your father, you

said that you had a much older family friend, Francis Davies, who provided you

with that nurturing male role.

33 You began your apprenticeship in Year 11 and you won awards in your first two

years. By your third year you had started smoking cannabis and your results

dropped off. You completed your four year apprenticeship at Brinton's Carpet

Manufacturing business.

34 You met and married Danielle, a hairdresser and artist and together had three

children. Tegan, aged 22, Callum, aged 20 and Leilani, aged 18. Your eldest son

is a qualified chef, a second son is in the second year of his apprenticeship

and your daughter has just completed her VCE.

35 You left Brinton's Carpet Manufacturers when you were around 25 years of age

and went to Western Australia, on the basis that, you needed more money to

support your family.

36 You returned to Geelong and worked as a contract fitter and turner for a

period of time and then you became employed at Alcoa. You became a team leader

there and ultimately worked your way into the area of environmental health, that

is, Occupational Health and Safety.

37 After some 11 years at ALCOA, you moved into a business working in that area

of environmental health. You left that business after two years and when you

did, the business failed shortly thereafter.

38 This would have been the period 2000 to 2002 and since about 2003 you have

worked on an on again, off again, basis with protracted periods of time on

social security benefits.

39 After about 13 years in your relationship with your ex-wife Danielle, that

relationship began to fail, you drifted apart, had a trial separation and never

reconciled. She re-married approximately three years ago.

40 Although you have a reasonably good relationship with your children, there

have been times, when you have had very little to do with them. There was a

point in time in which you became quite heavily involved with amphetamine.

41 Unfortunately, on the plea, nothing was put to me about your drug use or its

impact on you, as a person, at the time of the offending, prior to the time of

the offending, or subsequent to the time of the offending.

42 The only real reference I have in respect to this is contained in the report

of Michael Crewdson, psychologist where it states, at p.9, "The manic drive gave

way to a deep depression, 'I just couldn't get out of bed. There wasn't a clean

dish in the place. I had no motivation and I just wanted to sleep. Eventually, I

saw a doctor, started on a round of anti-depressants.' He told me, he also

started on amphetamines and 'they probably lifted me more than anything.' He

said he worked 'sporadically as a sub-contractor, often supervising plant

shutdowns and other maintenance.' He had a short-term contract at Karratha in

Western Australia, but said that, he 'took up poker machines like another drug'.

He said that for a couple of years up to 2004 he, 'Just didn't remember things.

I know I spent a lot of time sitting in the pub till late at night.'"

43 I am aware that you had some fairly substantial involvement in amphetamines

and potentially other drugs, which was material excluded from the evidence of

Jodi Harris. As I have no further information provided, other than what is in

the report by Mr Crewdson, I am unable to act on the basis of any real knowledge

about your drug taking or drug involvement.

44 All of this is very concerning, when attempting to look at your prospects of

rehabilitation. The only material available to me indicates, that this killing

occurred in relation to your anger about the money owed to you by the deceased

man, for rent. Whilst I am unaware of the precise manner in which you killed

him, I am satisfied that subsequent to that killing, you cut the body into

pieces and that you burnt those pieces and subsequently removed and distributed

the ashes and bone, in a manner such that, they have not been found.

45 I have also had the advantage of observing the record of interview that you

conducted with the police. It is chilling to watch. It indicates quite clearly

that you were playing word games and attempting to outwit and, to a degree,

patronise, the officers that were interviewing you, over this very serious

matter. That interview does not assist you, in any way. It does not give me

great comfort for your future, in terms of your rehabilitation.

46 The report of Mr Michael Crewdson indicates a past history of polysubstance

abuse and one major depressive episode of some years ago, and that you are

currently experiencing significant levels of anxiety and depression, which are

reactive to your current situation. It would appear that you suffer from no

psychological problems. Despite having no prior convictions and achieving the

age that you have, before committing this offence, I am not very confident about

your chances of long-term rehabilitation. There is no real explanation as to why

you murdered Trevor Tascas and your behaviour, both immediately after the

killing, with the destruction of his body, and the contemptuous manner in which,

you used and dealt with his possessions, gives me real concerns as to your

ability to change or modify your behaviour.

47 Whilst, when looking at the lack of prior convictions, this behaviour would

appear to be out of character, it persisted for some time and without

explanation.

48 There are four Victim Impact Statements in this matter, one from Trevor

Tascas' mother, two from his sisters and one from his father. One of the

features of anguish that they all talk about is, the inability to feel that this

matter is over, as there is no body, no way of saying goodbye to Trevor. A

memorial service has been held, but has failed to give the closure that any form

of burial or interment would.

49 Nothing that this court does will ever replace the son and brother that these

people have lost, but I will take into account their statements when determining

the appropriate sentence.

50 As well as those factors personal to you, to which I have referred, I also

have to take into account general and specific deterrence, both of which, in my

view, have a great deal of relevance to this case. There is also the need to

impose a just and appropriate sentence and to ensure that the sentence imposed

is not crushing.

51 Taking into account all of those matters and the others to which I have

referred, you are convicted on the one count of murder and sentence to be

imprisoned for a period of 23 years.

52 I direct that you are to serve 20 years before becoming eligible for parole.

53 I declare the amount of time spent in pre-sentence detention is 524 days and

that such be noted in the records of the court.

54 I will make the retention order.

|

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF

VICTORIA

|

Not Restricted

|

AT MELBOURNE

CRIMINAL DIVISION

S CR 2011 0178

|

THE QUEEN

|

|

|

|

|

v

|

|

|

|

|

LAWRENCE ALEXANDER BUTLER

|

Accused

|

---

|

JUDGE:

|

CROUCHER J

|

|

WHERE HELD:

|

Melbourne

|

|

DATES OF HEARING:

|

2-4, 9-13 & 16-19 September 2013

|

|

DATE OF REASONS:

|

13 December 2013

|

HIS HONOUR:

Introduction

1 On 9 September 2013, a jury of twelve persons was empanelled to hear the trial

of Lawrence Alexander Butler on a charge of manslaughter. It was alleged that,

between 5 and 12 October 2005 at Whittington, a suburb of Geelong, Mr Butler

killed Trevor John Tascas, who is also known as Trevor John Vanderwel. Mr Butler

had pleaded not guilty to that charge.

2 On 19 September 2013, after the close of the Crown case, the jury was given a

Prasad invitation.[1] The

jury declined to hear the trial further and instead returned a verdict of not

guilty.

3 During the course of the trial, I made several rulings but deferred giving

reasons, or detailed reasons, for those rulings. I now provide those reasons.

4 Before doing so, I shall set out the procedural history of the matter and then

a very brief summary of the Crown case and the defence case.

Procedural history

5 This was a retrial. Mr Butler was originally charged with murder in July 2008.

In 2009, he was tried on and convicted of that charge before King J and a jury

in Geelong. On 15 December 2009, King J imposed a sentence of 23 years’

imprisonment with a nonparole period of 20 years.[2]

6 Mr Butler appealed against his conviction. On 20 December 2011, the Court of

Appeal (Ashley JA and Ross AJA; Maxwell P dissenting) allowed the appeal,

quashed the murder conviction, directed an acquittal on that count and directed

a retrial on manslaughter.[3] All

members of the Court rejected a ground of appeal complaining, in effect, that

the judge erred in leaving various items of alleged behaviour or lies as going

to consciousness of guilt of murder. However, Ashley JA and Ross AJA upheld a

ground complaining it was not open to the jury upon the whole of the evidence to

convict Mr Butler of murder.

7 Mr Butler was bailed by King J for his retrial. He had spent in the order of

three years and eight months in custody.

8 On 26 November 2012, the matter came on before Curtain J in Geelong for

retrial on a fresh indictment charging manslaughter. However, because of

complications concerning the Crown’s principal witness Jodi Harris (who is also

known as Jodi Toulmin), the matter was taken out of the list on 27 November

2012.

9 Prior to the commencement of the retrial before me, Lasry J granted an

application for a change of venue to Melbourne as a result of the substantial

publicity surrounding the matter around the time it was heard as a murder trial

in Geelong.

Crown case

10 Very briefly, the Crown case was that, around the weekend of the Bathurst car

races in October 2005, Mr Butler had argued with Mr Tascas over rent, caused his

death by assaulting him in circumstances that amounted to manslaughter by an

unlawful and dangerous act, and then dismembered, burned and disposed of the

body.

11 Crucial to the Crown case was the witness Jodi Harris. Ms Harris was in an

intermittent relationship with Mr Butler at the relevant time. As will be seen

below, following an application under s

38 of the Evidence

Act 2008 (Vic), the prosecutor elicited from Ms Harris that she made a

statement to police in July 2008 (nearly three years after the disappearance of

Mr Tascas) in which she said the following:

a) Around the weekend of the Bathurst car races, Ms Harris went to Mr Butler’s

house in Thatcher Court in Whittington to have a shower. Mr Tascas was living

there at the time.

b) In the bathroom, she saw a large white hessian bag in the bathtub. Something

red in colour was leaking out of the bag. Mr Butler told her that he and his

mate had been fishing and there were fish in the bag.

c) After Ms Harris had a shower, she walked past Mr Tascas’s room and noticed a

sheet with a huge amount of blood on it sitting half on his bed and half on the

floor. As she went to leave, Mr Butler told her: “You know what you’ve seen, you

are now part of this”.

d) When back inside the house, Mr Butler told her that Mr Tascas’s “rent hadn’t

been paid, they had an argument and [Mr Tascas] got knocked out” and that Mr

Tascas “fell and hit his head and got knocked out”.

e) Mr Butler asked her what she thought had happened. She then said, as a joke,

“Is [Mr Tascas] in the bag?” Mr Butler said, “If you think that, then you can

come and help me.” Mr Butler then went to the bathroom and dragged the large

hessian bag out into the back yard, lifted the bag into a barrel and attempted

to set fire to it. Later that day, Ms Harris saw the drum smouldering.

f) A few days later, Mr Butler asked Ms Harris to go out the back and help him

clean up. He put a lot of the contents of the barrel into plastic shopping bags.

He threw a couple of the bags into a wheelie bin and more bags were left in the

barrel. He gave her a dustpan and brush to clean up the ash. She noticed

fragments of bone in the ash – some were as big as a finger, others were

smaller. Mr Butler rolled the barrel across the yard and put it into the boot of

Mr Tascas’s car (a maroon Calais). He drove Ms Harris to her house, dropped her

there and said he would be back soon. Later, when he returned in Mr Tascas’s

car, the barrel and the bags were no longer in the boot.

12 Ms Harris said that these things were true when she told police.

13 Ms Harris also gave evidence that, some time later (probably around

mid-November 2005, given telephone and bank records), she and Mr Butler

travelled to Queensland in Mr Tascas’s car. The car was left in Queensland.

14 There was evidence that rumour had it that, around July 2005, Mr Tascas may

have sexually assaulted a 13-year-old girl (“CM”). CM was the daughter of a

woman with whom Mr Butler had a relationship of sorts. There was evidence that

Mr Butler was aware of the rumours and that, when told of them, he may have been

angry. The Crown relied on this as evidence of a motive for Mr Butler to assault

Mr Tascas.

15 There was evidence that Mr Tascas was very attached to his small dog named

Lulu. Nicole Donaghy gave evidence that, perhaps about two months after Mr

Tascas’s disappearance, Mr Butler indicated to her that he had been left in

effect to care for Lulu, that Mr Tascas had “taken off” and would not be coming

back, and that she could take Lulu if she wished, which she did.

16 Ms Harris gave evidence that, between July and August 2006, she and her

former husband Troy Harris stole about $11,000 from Mr Tascas’s bank account. Ms

Harris accepted that Mr Butler was not aware of this theft.

17 There was no forensic evidence discovered at Thatcher Court. Mr Tascas’s body

has never been found. Apart from some thin evidence of possible sightings, there

was evidence that Mr Tascas has not been seen or heard of since October 2005.

Other than the theft between July and August 2006 and his disability pension

going into the account on a regular basis, Mr Tascas’s bank account had not been

accessed since October 2005. Inquiries with other banks and agencies also

suggested Mr Tascas was deceased.

18 In his police interview, conducted in July 2008, Mr Butler agreed that he was

aware of the rumours about Mr Tascas being involved with a girl of 14 or 15, and

that he possibly spoke to Mr Tascas about them, but there was no admission that

he was angered by this information. He said Mr Tascas told him he was going to

the Bathurst car races but he had not seen him since. Mr Butler denied any

involvement in the death of Mr Tascas.

Defence case

19 During his defence response and through cross-examination, counsel for Mr

Butler made clear his client’s defence: First, he disputed that Mr Tascas was

dead. Secondly, if Mr Tascas was dead, the allegation that he was killed by Mr

Butler – which was denied – turned wholly upon Ms Harris, who could not be

believed. Amongst other things, Ms Harris conceded in cross-examination that,

today, she did not know if what she what she had told police she witnessed at

Thatcher Court was true and that she was simply unable to say whether those

events occurred. Thirdly, even if satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that what Ms

Harris told police actually occurred, it did not amount to evidence that Mr

Butler killed Mr Tascas. There was also other evidence in the case suggesting

that others killed Mr Tascas. Fourthly, even if satisfied beyond reasonable

doubt that what Ms Harris told police meant that Mr Butler had caused Mr

Tascas’s death, the killing did not amount to an unlawful and dangerous act.

Ruling No 1: Incriminating conduct – Disposal of remains – Use of car

Application by Crown

20 In pre-trial argument before me on 2 September 2013, the Director of Public

Prosecutions filed a notice (dated 1 September 2013) pursuant to s 23 of the

Jury Directions Act 2013 (Vic) (“the JD Act”) stating that “the prosecution

intends to adduce evidence of conduct that it proposes to rely on as evidence of

incriminating conduct”. The notice then set out the following pieces of alleged

conduct on which the Crown intended to rely:

(a) the accused dismembered and burnt the deceased’s body and then

disposed of his remains;

(b) the accused drove the deceased’s maroon Calais to Queensland and

disposed of same;

(c) the accused told investigators in his record of interview:

(i) that he did not know if the deceased had taken his vehicle with him

when he went to Bathurst;

(ii) that he did not know what had happened to the deceased’s dog Lulu;

(iii) that the deceased had made arrangements for the dog to be cared for in his

absence; and

(iv) that the deceased had told the accused that he intended to travel to

Bathurst.

Extension of time

21 Since Mr Butler had not been arraigned on this indictment before a jury, the

JD Act did not yet apply. However, as he was about to be arraigned shortly

during the jury empanelment process, from which time the JD Act would apply,[4] the

parties were content to proceed on the understanding that the matter should be

considered as if it were governed by the JD Act.

22 Section 3(1) of the JD Act provides that the notice must be filed and served

at least 28 days before the day on which the trial is listed to commence. An

earlier version of the notice was filed and served on 27 August 2013. The new

version was filed and served on 2 September 2013, the day the trial was due to

commence. Thus, the notice was filed and served late.

23 Section 7(1) of the JD Act allows the court by order to extend or abridge any

time fixed by or under the JD Act if the court considers that it is in the

interests of justice to do so.

24 For reasons that follow, I was of the view that it was in the interests of

justice to extend or abridge the time for the filing of the notice. First, the

pieces of allegedly incriminating conduct relied on were, in substance, the same

as those relied on at the first trial as evincing a consciousness of guilt and

which were the subject of discussion in the judgment of the Court of Appeal.

Thus, there was nothing new or surprising in the submissions being put on behalf

of the Crown. Secondly, the evidence, if admissible as incriminating conduct,

was likely to be important to the Crown case.

25 I decided not to make the order extending or abridging time until after Mr

Butler was arraigned in the presence of the jury panel so that the JD Act would

in fact be applicable at that time.[5]

Counsel’s arguments

26 As to the merits of the application, Mr Bourke, who appeared for the Crown,

relied on inter alia the reasons of the Court of Appeal in rejecting the

argument in that Court that the same behaviour could not amount to consciousness

of guilt of murder. He also referred to R v Rice [1996] 2 VR 406 and R v

Ciantar [2006]

VSCA 263; (2006)

16 VR 26.

27 Mr Desmond, who appeared for the accused, did not argue that any of this

evidence was inadmissible per se. Rather, his submission was that, in respect of

items (a) and (b) in the notice, the behaviour relied on could not be used as

incriminating conduct and, in respect of items (c)(i)-(iv), they did not amount

to lies and, even if they did, they could not be used as incriminating conduct.

28 On 3 September 2013, I indicated that, at some point after arraignment in the

presence of the jury panel, I would be ruling as follows (which rulings were in

fact made in the absence of the jury after empanelment and arraignment):

Item (a): Alleged dismembering, burning and disposal of body

29 First, as to item (a) in the notice, where the conduct relied on was that Mr

Butler dismembered and burnt Mr Tascas’s body and then disposed of his remains,

in my view, subject to one exception, it was open to leave that alleged conduct

as evidence of incriminating conduct.

30 The evidence for this conduct was expected to come entirely from Ms Harris

and from inferences to be drawn from her evidence. If the substance of her

anticipated version of events were accepted, it would be open to the jury to

find that Mr Butler placed Mr Tascas’s body in a drum, burnt it and then

disposed of the remains (which, hereafter, I shall refer to collectively as the

disposal of the body). Whether it would be open to infer that the body had been

dismembered was not so clear. In any event, if the jury concluded that Mr Butler

had disposed of the body, it would be open to use that evidence as evidence that

he believed that he had committed the offence of manslaughter, or an element of

it, and that the only reasonable explanation of the conduct was that Mr Butler

held that belief.

31 I formed the view that the disposal of the body is behaviour capable of being

regarded as so disproportionate to an accidental or otherwise innocent killing,

or to lack of involvement at all in a killing, that it was open to leave the

alleged behaviour as incriminating conduct. In R v Rice [1996] 2 VR 406 at 412,

Brooking JA, when dealing with a case in which a person had concealed a body in

a lime-filled drum and told lies regarding the deceased’s movements and plans,

asked rhetorically, “Why should a man take such a risk if the explanation for

her death was an innocent one?” Whilst there were numerous good arguments to be

put on behalf of Mr Butler that might explain that alleged behaviour in a manner

consistent with innocence of manslaughter, including those stemming from the

alleged admission to Ms Harris of an account consistent with accident or the

commission of some lesser offence, none of those arguments was so compelling as

to render the evidence “intractably neutral”[6] or

otherwise inadmissible as incriminating conduct. Rather, these were all matters

for a properly directed jury to consider in determining whether the evidence, if

accepted, did disclose incriminating conduct.

32 In coming to this view, I also took into account that the evidence of

disposal of the body by the accused was disputed, was not supported by any

forensic evidence whatsoever and instead was to come solely from a combination

of direct evidence from Ms Harris and inferences to be drawn from her evidence,

in circumstances where Ms Harris was a witness about whom, even at that stage of

the trial, it was obvious there would have to be some form of unreliable

evidence direction.

33 Finally, as indicated above, the Court of Appeal rejected an argument that

this evidence, and the other pieces of evidence relied on, should not have been

left as going to consciousness of guilt of murder.[7] Whilst

consciousness of guilt of murder (by an intention to kill or cause really

serious injury) and consciousness of guilt of manslaughter (by an unlawful and

dangerous act) are different things, not least because the former crime involves

a purely subjective intention whereas the latter involves a mixture of a lesser

subjective intention (in this case, the intention to commit some sort of

assault) and an objective awareness (as to dangerousness), nevertheless,

generally speaking, and in this case, the greater will include the lesser, and I

was satisfied that the behaviour relied on could go to a consciousness of guilt

of manslaughter. Moreover, it is at least implicit in the Court of Appeal’s

reasons that the same behaviour (as well as the driving and disposal of the car

and the alleged lies) could go to a consciousness of guilt of manslaughter.

34 I should add that, at least for the purposes of this case, I considered that

there was no meaningful difference between the common law concept of

consciousness of guilt or post-offence conduct and the JD Act concept of

incriminating conduct.

Item (b): Driving Mr Tascas’s car to Queensland and disposing of same

35 Secondly, as to item (b) in the notice, where the conduct relied on was that

Mr Butler drove Mr Tascas’s car to Queensland and disposed of the same, again,

in my view, it was open to leave that alleged conduct as evidence of

incriminating conduct.

36 Again, the evidence for that conduct was expected to come principally from Ms

Harris. While this evidence was not disputed, Mr Desmond foreshadowed that there

may be evidence elicited from Ms Harris and others that showed the trip to

Queensland was taken at Ms Harris’s instigation and was drug-related. However, I

reasoned that that would not necessarily alter the view that, if the jury

accepted that Mr Tascas’s car was driven by Mr Butler to Queensland and disposed

of, it would be open to the jury to use that evidence, particularly in

combination with the evidence of disposal of the body, as evidence that Mr

Butler believed that he had committed the offence of manslaughter, or an element

of it, and that the only reasonable explanation for the conduct was that Mr

Butler held that belief.

37 Whilst this behaviour was not as extreme – and therefore, in my view, not as

probative – as the alleged disposal of Mr Tascas’s body, I formed the view that

it was open to the Crown to argue, and for a jury to reason, that only a person

who had unlawfully caused the death of Mr Tascas would use the car in this

fashion.

Items (c)(i)-(iv): Alleged lies in record of interview

38 The third set of items relied on in the notice was a series of alleged lies

told by Mr Butler to police in his record of interview. The interview was

conducted in July 2008, nearly three years after the alleged disappearance of Mr

Tascas.

39 Whilst it was argued in the Court of Appeal that the alleged lies (and other

alleged post-offence conduct) should not have been left as going to

consciousness of guilt of murder, it does not appear to have been argued that it

was not open to conclude that the alleged lies were in fact lies.

40 As to item (c)(iv) in the notice (namely, that Mr Tascas had told Mr Butler

he intended to travel to Bathurst), Mr Bourke did not pursue this item. Instead,

he conceded at the outset that the evidence could not exclude the reasonable

possibility that Mr Tascas did in fact say such a thing to Mr Butler at some

relevant point. Accordingly, I did not need to rule on this particular item.

41 As to items (c)(i), (ii) and (iii) in the notice, I decided that I would

prefer to hear the evidence in the trial before ruling on whether these alleged

lies were capable of being lies and, if so, whether they were capable of

amounting to incriminating conduct. In that regard, for example, Mr Bourke

indicated he intended to ask Ms Harris questions about the dog that had not been

asked at the previous trial or the committal hearing. It was thought that other

witnesses might also have new evidence relevant to this issue. Thus, I deferred

until the close of the Crown case any further argument and ruling on that issue.

I shall deal with that matter in Ruling No 6, below.

Ruling No 2: Discharge of jury because of alleged irregularity in empanelment

Introduction

42 Very soon after the first jury was empanelled on 3 September 2013, and before

opening addresses, Mr Desmond made an application that the jury be discharged

without verdict on the basis of alleged irregularities in the manner in which

some jurors were administered the oath. Mr Bourke did not formally concede that

the application should succeed, but he indicated that he was troubled about the

matter and that a cautious approach – i.e. one favouring discharge – might be

wise, particularly given that it was so early in the piece. After a good deal of

hesitation, I granted the application and discharged the jury without verdict.

Background

43 During the empanelment process, the twelve jurors who ultimately formed the

first jury were dealt with in three different manners: first, there were those

who were sworn; second, there was one juror who made a promise; and, third,

there were some who took affirmations.

44 After the twelve jurors were selected, each was identified by my associate

and asked to stand. I explained that jurors could take an oath by swearing or

promising or they could make an affirmation. My associate then said, “Any juror

wishing to take an oath, please raise the Bible in your right hand”. She then

said, “Any juror wishing to make a promise, please be seated whilst the oath is

taken [and] any juror wishing to make an affirmation, please be seated whilst

the oath is taken”.

45 Each of those jurors who remained standing did in fact raise the Bible in his

or her right hand. The oath was administered to them as a group, as follows:

“You and each of you swear by Almighty God that you will faithfully and

impartially try the issues between the Crown and [the accused] in relation to

all the charges brought against [the accused] in this trial and give a true

verdict according to the evidence”. Each was asked to respond, and did respond,

in turn: “I swear by Almighty God to do so”.

46 The juror who took an oath by promising was then dealt with separately. He

did not have a Bible in his hand. He was not asked by my associate or me whether

or not he wished to have a Bible in his hand. The oath administered to him read:

“You promise by Almighty God that you will faithfully and impartially try the

issues between the Crown and [the accused] in relation to all the charges

brought against [the accused] in this trial and give a true verdict according to

the evidence”. He was asked to respond, and did respond: “I promise by Almighty

God to do so”.

47 Those taking an affirmation were dealt with next. The affirmation

administered to them read: “You and each of you solemnly and sincerely declare

and affirm that you will faithfully and impartially try the issues between the

Crown and [the accused] in relation to all charges brought against [the accused]

in this trial and give a true verdict according to the evidence”. Each was asked

to respond, and did respond, in turn: “I do so declare and affirm”.

48 During Mr Desmond’s application, my tipstaff advised to the effect that, as

jurors made their way to the jury box during empanelment, as well as taking

their effects or the like, he asked whether they wished to be sworn, make a

promise or make an affirmation and whether anyone wanted to have a Bible. Those

who indicated they wanted to be sworn took a Bible. This information was

conveyed to the parties during the application.

Arguments of counsel

49 As I understood Mr Desmond, he submitted in effect that there were four

faults with that process. The first argument was that, when those who swore an

oath were asked, “Any juror wishing to take the oath, please raise the Bible in

your right hand”, they were not given a choice as to whether they did or did not

hold a Bible at the time of taking that oath.

50 The second argument was that the juror who made a promise was not asked

whether he wished to have a Bible, and accordingly was not given the option of

having a Bible at the time of taking that oath.

51 The third argument was that the jurors who swore and the juror who promised

should have been dealt with jointly as one group, not separately as two groups.

He said that that is the usual (although not invariable) practice in the County

Court. Mr Bourke said that that was his experience too.

52 The fourth argument, which was not pressed as firmly, was that, in so far as

my tipstaff spoke to jurors about whether they wished to swear, promise or

affirm and have a Bible or not, whilst it was something that happened in court,

it was not something that either he or his client was aware was occurring at the

time and therefore could not be said to have occurred in open court.

53 Mr Desmond also submitted that, for any or all of those reasons, there was a

breach of the relevant legislation; and that there was, in consequence, a high

degree of need to discharge the jury. He added that breaches of provisions

concerning the administering or constitution of juries were sometimes fatal to

convictions on appeal. Finally, he submitted that, since this was the very

earliest stage of the trial, the level of inconvenience in discharging a jury

was at its lowest point, such that, if there were any doubt about the matter,

the balance of convenience favoured discharging the jury.

54 As indicated above, Mr Bourke did not formally concede that the application

should succeed, but he suggested that a cautious approach – i.e. one favouring

discharge – might be wise, particularly given that it was so early in the piece.

Put another way, as Mr Bourke did, were this the second or third week of a

three-week trial, a judge might take a different view of the application.

Initial thoughts

55 My initial reaction to all of this was that it was a very ambitious

application. At the time I discharged the jury, I was not confident that the

application had merit. But I was troubled at the idea that, if I were wrong

about the matter, a trial might be conducted with an unlawfully constituted

jury, which would be unfair for both Mr Butler and the Crown and potentially a

great waste of time and resources. As a result of my own uncertainty and because

it was so early on in the piece, I found it easier to be persuaded that the

application should succeed.

The better view

56 On reflection, whilst I should have conducted the process differently in

order to conform more precisely with the mandates of s 42 and Schedule 3 of the Juries

Act 2000 (Vic) (“the Juries

Act”), and indeed I have since altered the way in which I conduct that

process, I think I was wrong to discharge the jury.[8] Before

explaining my reasons for those conclusions, I shall set out some of the

relevant provisions:

Section 42 and Schedule 3 of the Juries

Act 2000 (Vic)

57 Section

42 of the Juries

Act provides that, “[o]n being empanelled, jurors must be sworn in open

court in the form of Schedule 3 applicable to the case”. Schedule 3 provides as

follows:

SWEARING OF JURORS ON

EMPANELMENT

Oaths by jurors—Criminal

Trial

You (or, if more than one person takes the oath,

you and each of you) swear (or the person

taking the oath may promise) by Almighty God (or

the person may name a god recognized by his or her religion) that you will

faithfully and impartially try the issues between the Crown and [name

of accused] in relation to all charges brought against [name

of accused] in this trial and give a true verdict according to the evidence.

Oaths by jurors—Civil Trial

You (or, if more than one person takes the oath,

you and each of you) swear (or the person

taking the oath may promise) by Almighty God (or

the person may name a god recognized by his or her religion) that you will

faithfully and impartially try the issues and assess the damages in the cause

brought before you for trial or inquiry and give a true verdict according to the

evidence.

Affirmations by

jurors—Criminal Trial

You (or, if more than one person affirms, you

and each of you) solemnly and sincerely declare and affirm that you will

faithfully and impartially try the issues between the Crown and [name

of accused] in relation to all charges brought against [name

of accused] in this trial and give a true verdict according to the evidence.

Affirmations by jurors—Civil

Trial

You (or, if more than one person affirms, you

and each of you) solemnly and sincerely declare and affirm that you will

faithfully and impartially try the issues and assess the damages in the cause

brought before you for trial or inquiry and give a true verdict according to the

evidence.

Division 2 of Part

IV of the Evidence

(Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1958 (Vic)

58 Division 2 of Part

IV of the Evidence

(Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1958 (Vic) (“the EMP Act”) deals with oaths

and affirmations. Section 100 provides that Division 2 does not apply to an oath

or an affirmation made by a witness in a proceeding or by a person acting as an

interpreter in a proceeding to which the Evidence

Act 2008 (Vic) (“the Evidence

Act”) applies. No part of Division 2 is expressed to apply to jurors taking

oaths or affirmations. On the other hand, apart from the limitation imposed by s

100, the provisions of Division 2 appear to be of general application and

may be seen as supplementing the relevant aspects of the Juries

Act, even though the latter Act has its own particular provisions concerning

the taking of oaths or affirmations by jurors upon empanelment. It will be seen

that there is, in any event, a degree of commonality between the provisions

concerning, and prescribed forms of, oaths and affirmations in the Juries

Act and the EMP Act (as well as the Evidence

Act).

59 Section 101(1) of the EMP Act provides that a person may take an oath or make

an affirmation in accordance with the appropriate form set out in Part 1 of the

Third Schedule or in a similar form. Part 1 of the Third Schedule provides as

follows:

PART 1—FORM OF OATH AND

AFFIRMATION

Form of oath

I swear (or the person taking the oath may promise) by Almighty God (or the

person may name a god recognised by his or her religion) that (followed by the

words of the oath prescribed or allowed by law).

Form of affirmation

I solemnly and sincerely declare and affirm that (followed by the words of the

oath prescribed or allowed by law).

60 Section 101(3) provides

that an oath or affirmation may be administered to and taken, or made, by two or

more persons at the same time.

61 Section 102(1) provides that a person who is required to take an oath may

choose whether to take an oath or to make an affirmation. Section 102(2)

provides that the officer administering the oath or affirmation is to inform the

person that he or she has this choice, unless the officer is satisfied that the

person has already been informed or knows that he or she has the choice.

62 Section 103(1) provides that it is not necessary that a religious text be

used in taking an oath. Section 103(2) provides that an oath is effective even

if the person who took it did not have a religious belief or did not have a

religious belief of a particular kind.

63 Whilst the form of oath in Part 1 of the Third Schedule to the EMP Act is

essentially the same as the form of oath in Schedule 3 of the Juries

Act, there are no express equivalents of ss 101, 102 or 103 of the EMP Act

in the Juries

Act.

Division 2 of Part

2.1 of Chapter 2 of the Evidence

Act 2008 (Vic)

64 Division 2 of Part

2.1 of Chapter 2 of the Evidence

Act deals with oaths and affirmations of witnesses and interpreters in

proceedings.

65 Sections

21(4) and 22(2)

provide in effect that, where a witness (or an interpreter) in a proceeding is

required to take an oath or make an affirmation, the witness (or interpreter) is

to take the oath, or make the affirmation, in accordance with the appropriate

form in Schedule 1 or in a similar form. Schedule 1 provides as follows:

OATHS AND AFFIRMATIONS

Sections 21(4) and 22(2)

Oaths by witnesses

I swear (or the person taking the oath may

promise) by Almighty God (or the person may

name a god recognised by his or her religion) that the evidence I shall give

will be the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

Oaths by interpreters

I swear (or the person taking the oath may

promise) by Almighty God (or the person may

name a god recognised by his or her religion) that I will well and truly

interpret the evidence that will be given and do all other matters and things

that are required of me in this case to the best of my ability.

Affirmations by witnesses

I solemnly and sincerely declare and affirm that the evidence I shall give will

be the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

Affirmations by interpreters

I solemnly and sincerely declare and affirm that I will well and truly interpret

the evidence that will be given and do all other matters and things that are

required of me in this case to the best of my ability.

66 Section

23(1) provides that a person who is to be a witness or act as an interpreter

in a proceeding may choose whether to take an oath or to make an affirmation. Section

23(2) provides that the court is to inform the person that he or she has

this choice, unless the court is satisfied that the person has already been

informed or knows that he or she has the choice.

67 Section

24(1) provides that it is not necessary that a religious text be used in

taking an oath. Section

24(2) provides that an oath is effective for the purposes of Division 2 even

if the person who took it did not have a religious belief or did not have a

religious belief of a particular kind or did not understand the nature and

consequences of the oath.

68 It will be noted that ss

23 and 24 of

the Evidence

Act are in similar terms to ss 102 and 103 of the EMP Act and that the form

of oath in Schedule 1 is essentially the same as the forms of oath in the EMP

Act and the Juries

Act.

What is required when administering oaths or affirmations to jurors?

69 There are several things to note about s

42 and Schedule 3 of the Juries

Act and the provisions of Division 2 of Part

IV of the EMP Act and Part 1 of the Third Schedule.

70 First, the use of the word “must” in s 42 connotes that the requirements set

out in Schedule 3 are mandatory.

71 Secondly, my reading of Schedule 3 is that it allows, but does not require,

that, if two or more jurors take an oath, the oath may be administered to them

at the same time. The same is true of jurors making an affirmation. To the

extent that s 101(3) of the EMP Act applies to jurors, the same point is made

plain, as the permissive “may” is used, not the mandatory “must”. Obviously, it

is more efficient to do it this way, if practicable.

72 Thirdly, Schedule 3, read with s 42, provides that a juror taking an oath

must swear or promise by Almighty God or by a god recognised by his or her

religion. Thus, a juror could swear by Almighty God, promise by Almighty God,

swear by a god recognised by his or her religion or promise by a god recognised

by his or her religion. Part 1 of the Third Schedule of the EMP Act allows for

the same four possible combinations. (The same is true of Schedule 1 of the Evidence

Act.)

73 Fourthly, it appears that there is no provision that expressly provides for

the taking of an oath by the making of a promise (as opposed to swearing).

Rather, this option derives from the terms of Schedule 3 in the Juries

Act, Part

1 of the Third Schedule to the EMP Act and Schedule 1 of the Evidence

Act. Nor is there any provision which expressly recognises three separate

categories – oaths, promises and affirmations. Rather, as appears from those

schedules, there are two categories – oaths and affirmations; and to swear or

promise (by Almighty God or a god recognised by the juror’s religion) are simply

alternative ways of taking an oath.

74 Fifthly, nothing in Schedule 3 requires that a religious text be used when

taking an oath. Section 103(1) of the EMP Act (and s

24 of the Evidence

Act) make the same point by expressly stating that it is not necessary that

a religious text be used in taking an oath. Equally, it would not be

inconsistent with either the Juries

Act or the EMP Act (or the Evidence

Act) that a juror be provided with a religious text to hold or have nearby

when taking an oath, whether it be the Bible, the Koran or any other religious

text.

75 Thus, in light of the foregoing, and with the concurrence of the parties, for

the next jury, I altered the way in which jurors were administered oaths or

affirmations upon empanelment. In particular, before my associate administered

an oath or affirmation to them, I told the jurors that they could take an oath

or make an affirmation and that each is equally binding. I then said:

If you wish to take an oath, you may do so by swearing, or promising, by

Almighty God, or by a god recognised by your religion, and you may do so with or

without a Bible or other religious text. If you wish to have a Bible or other

religious text when taking an oath, please indicate now or when asked by my

associate.

76 I explained that those taking an oath would have it administered to them in a

particular form, whereupon I read from the oath in Schedule 3 (which was

probably unnecessary). I then explained that my associate would then ask each of

them to respond, “I swear, or promise, by Almighty God to do so”, but that it

was up to each individual juror in responding, where appropriate, to choose

either the word “swear” or the word “promise” and either the words “Almighty

God” or the name of a god recognised by the juror’s religion.[9]

77 I then explained the equivalent process for those affirming.

78 I asked jurors if they wanted me to repeat the information. None took up that

invitation.

79 My associate then went through the foreshadowed process. Bibles were handed

to those who requested them. No one requested another religious text. The

process worked. That said, not surprisingly, at least one juror (the first)

taking an oath was a little unsure as to whether to say “swear and promise”

rather than either “swear” or “promise”, but that was sorted out easily.

80 There are of course other (and, no doubt, preferable) ways to undertake this

process and still comply with the relevant provisions. My method was a tad

long-winded and cumbersome, but was consistent with the submissions of the

parties and with the relevant provisions.

Why I was wrong to discharge the jury

81 I now turn to deal with counsel’s submissions.

82 First, contrary to Mr Desmond’s submission, the use of the words “Any juror

wishing to take the oath, please raise the Bible in your right hand” did not

deprive jurors of a choice as to whether they did or did not hold a Bible at the

time of taking that oath. (In this context, “tak[ing] the oath” meant those

swearing.) Similarly, the juror who took an oath by making a promise was not

deprived of the option of having a Bible at the time of taking that oath. All

jurors were given the option, through my tipstaff, of having a Bible if they

wished. Those who took a Bible from my tipstaff ended up being those who raised

the Bible when asked to do so. The juror who took the oath by making a promise

had not taken up that option when it was offered to him. I detected nothing

either in those who took up the Bible, or in the one who did not, that suggested

they were being deprived of a choice in this regard.

83 Secondly, the complaint that the jurors who swore and the juror who promised

should have been dealt with jointly as one group, and not separately as two

groups, should be rejected. It may well be the common practice in the County

Court. Plainly, it is more efficient to do it that way. Further, as I have

indicated above, that is that way in which I did so with the later jury

(although none of those jurors made a promise; all swore). But, as I also

indicated above, my reading of Schedule 3 is that it allows, but does not

require, that, if more than one juror takes an oath, the oath may be

administered to them at the same time. To the extent that s 101(3) of the EMP

Act applies to jurors, this also makes it plain, as the permissive “may” is

used, not the mandatory “must”. Thus, despite my initial concern about the

point, I do not see any error in administering oaths separately or jointly to

jurors. The same is true of administering affirmations.

84 Thirdly, whilst I accept it would have been preferable if the possibility of

having a Bible (or other religious texts) had been explained to the jurors by me

or my associate within the hearing of the parties rather than by my tipstaff

beyond the hearing of the parties, I do not accept that the fact that some

information was conveyed by my tipstaff without the knowledge of the parties at

that particular time deprived the process of its open character. The matter was

brought to the parties’ attention almost immediately. The minute the matter was

raised, counsel accepted that what was conveyed to me and then to the parties

was accurately conveyed. As also indicated above, it is not necessary that a

religious text be used in taking an oath but a religious text may be used.

Accordingly, being offered the opportunity to take a religious text did not, in

the circumstances, involve a breach of the provisions or otherwise deprive the

process of its validity.

85 Finally, I am satisfied that those who took an oath – whether by swearing or

promising to Almighty God, with or without a Bible – did so in a free exercise

of choice and with an understanding of the solemnity of the occasion. The same

is true of those who made an affirmation. If there was any breach of the

provisions, it was not such as to render the jury wrongly constituted; nor would

there have been any miscarriage of justice in carrying on with the trial at that

point.

86 Accordingly, I was wrong to discharge the jury on the basis of the arguments

put to me.[10]

Ruling No 3: Request for release of transcript

87 At the commencement of the trial, there was a request by a media organisation

to be provided with an electronic copy of the transcript in this trial on a

daily basis. On 3 September 2013, I granted the application but also made a

suppression order to ensure that there was no reporting of sensitive matters

that were not in evidence about the previous history of the matter. My reasons

for making those orders follow:

88 As I understand it, requests of this type are commonly made and commonly

acceded to in this Court. It seems to be a sensible practice. It has the virtues

of allowing journalists to check their own record of the trial (if they have

been in court) against the transcript, of ensuring that they have as accurate a

record of the evidence as is reasonably possible short of hearing the evidence

themselves (if they have not been in court) and of relieving them of the need to

be in court for every minute of a trial in order to report on it.

89 There might be occasions on which release of an electronic copy of the

transcript would not be appropriate or even authorised. For example, it might be

inappropriate to release such transcript where there is a dispute between the

parties about the accuracy of the transcript on an important piece of evidence.

The transcript of evidence that is heard in closed court might not be released

for the same reasons that the court was closed in the first place. Neither of

those situations applied here.

90 However, there were other important considerations in this case. As indicated

above, Mr Butler was previously tried on, and convicted of, a count of murder.

That conviction was set aside on appeal and a retrial was directed on

manslaughter, not murder. Further, the principal Crown witness in that previous

trial was, and in this trial was about to be, Jodi Harris. Ms Harris pleaded

guilty to being an accessory after the fact to manslaughter. She received a

suspended gaol sentence for that offence but was subsequently dealt with for

breaching that suspended sentence as well. Recently, Ms Harris’s appeal

concerning her sentence was heard and determined in the Court of Appeal.

91 The parties agreed, and I accepted, that, unless the matter were raised

during evidence in the retrial, the jury should not be made aware of the fact

that Mr Butler was previously tried on and convicted of a count of murder.

92 With that in mind, I requested that the sentences and judgments in Mr Butler

and Ms Harris’s previous proceedings temporarily be taken down from legal

databases such as Austlii, which I believe occurred.

93 Another relevant factor was that there was substantial publicity of this

matter around the time it was heard as a murder trial in Geelong. As a result of

that publicity, as indicated above, another Judge of this Court acceded to an

application that the venue of the retrial on manslaughter be changed from

Geelong to Melbourne.

94 Mr Desmond was concerned that releasing an electronic copy of the transcript

in this trial on a daily basis would risk further publicity and in turn risk a

juror or jurors inadvertently finding out that Mr Butler was previously tried on

and convicted of a count of murder. Jurors were instructed not search databases

for information concerning this matter and to keep their own counsel about the

case. But there is always some risk that jurors will learn of information from

outside the court room about previous proceedings, including through the media.

95 I formed the view that that risk could be ameliorated by the making of a

suppression order pursuant to s

18 of the Supreme

Court Act 1986 (Vic) on the basis spelt out in s

19(b), namely that it was necessary to do so in order not to prejudice the

administration of justice.

96 Accordingly, pursuant to s

18 of the Supreme

Court Act 1986 (Vic), until verdict in the trial, I prohibited publication

(a) of the fact that the accused was previously tried on, convicted of and

sentenced for a count of murder, (b) of the fact that that conviction was set

aside on appeal and (c) of any of the contents of the previous committal

hearings, trials, plea hearings, sentences or appeals concerning the accused and

Jodi Harris (aka Jodi Toulmin), except to the extent that such information was

disclosed in evidence during the running of the trial.

97 Once that order was made, I allowed the release of the electronic transcript

of the trial each day to the media organisation that requested it.

Ruling No 4: Crown application to cross-examine own witness

98 During Ms Harris’s evidence-in-chief, after giving evidence of general

matters including identifying photographs of Mr Butler’s house in Thatcher

Court, she was asked whether something unusual happened one day at the house

when she went there to have a shower. (This, of course, was the lead-in to the

alleged incident concerning Mr Butler’s admission to her and their involvement

in disposal of the body.) At that point, Ms Harris asked for a break, which was

granted. During the break, Mr Bourke was advised that the witness was reluctant

to proceed. When the matter was recalled, Mr Bourke repeated the question he

asked before the break. Ms Harris said that she did not remember. She was asked

further questions and said that she had “just, like, blocked the whole thing

out”. She went on to say, “I don’t remember a lot, it was such a long time ago”,

“I am very blank” and similar things.

99 Mr Bourke then made an application, in the absence of the jury and the

witness, for leave to cross-examine Ms Harris pursuant to s

38(1)(b) of the Evidence

Act 2008 (Vic). In particular, he submitted that, given she had made a

statement about the matter and that she had given evidence on this topic at the

last trial, Ms Harris may reasonably be supposed to have knowledge of the matter

and that she was not making a genuine attempt to give the relevant evidence. The

application was opposed by Mr Desmond.

100 I resolved that the witness should be called on a voir dire in order to

determine whether she was or was not making a genuine attempt to give the

relevant evidence. I was concerned that, given her history (including a history

of heavy drug use) and the passage of time, she may just have been unable to

remember. On the voir dire, I explained to Ms Harris her obligation to tell the

truth.[11] She

did not claim to be unwell or affected by drugs. I asked her directly about the

incident at Thatcher Court. She said she did not remember a lot, that she did

not know. She said she had not read her statement. She was asked questions about

going to Queensland and about stealing the money from Mr Tascas’s account, and

seemed to answer those questions reasonably coherently, albeit her memory of

some of the detail was a little vague. She denied being frightened of giving

evidence. She reiterated that she did not remember a lot and that she could only

remember bits and pieces.

101 Ms Harris was asked further questions by both counsel. In cross-examination

by Mr Desmond, Ms Harris said she was unable to say that she saw Mr Butler

dragging a hessian bag out of the house and placing it into a drum or that he

burned any such thing. She conceded that she had experienced hallucinations

during and after drug use. However, in re-examination by Mr Bourke, Ms Harris

said she remembered telling the police the things in her statement; and that

those things were true when she said them.

102 Having heard Ms Harris’s evidence before the jury to that point and on the

voir dire, and having regard to her police statement and the evidence she had

given at the previous trial, whilst I considered it reasonably possible that she

simply could not remember the detail of the matter, I concluded on balance that

Ms Harris was not making a genuine attempt to give evidence about a topic she

may reasonably be supposed to have knowledge, namely the alleged incidents at

Thatcher Court.

103 I had regard to the fact that a decision to grant leave under s

38 also involves the exercise of a discretion. In considering that

discretion, I considered the matters spelt out in ss

38(6) and 192(2)

of the Evidence

Act. Having regard on the one hand to the potential unreliability of Ms

Harris’s evidence but on the other to the importance of the evidence to the

Crown case in this trial (a homicide trial, no less), I concluded that it was

appropriate to grant Mr Bourke’s application.

104 However, given that Ms Harris did seem to be able to give evidence about the

trip to Queensland and other matters such as the stealing of the money from Mr

Tascas’s bank account, I limited the cross-examination by the Crown to putting

to her those parts of her statement that concerned the alleged incidents at

Thatcher Court.[12]

105 Mr Bourke then completed what he could of Ms Harris’s evidence-in-chief

before the jury by asking non-leading questions (regarding the trip to

Queensland and other matters) and then returned to the incidents at Thatcher

Court, whereupon he put to her, in the manner of cross-examination, parts of her

statement concerning those issues. The witness agreed that she had said those

things to police in her statement and that they were true when she told the

police. In cross-examination by Mr Desmond, however, Ms Harris conceded that she

did not know if any of that was true because, today, she was unable to say that

those events occurred. More of this later.

Ruling No 5: Closure of Court for witness’s evidence of sexual abuse as a child

106 During the trial, the Crown called a witness whom I shall call CM. CM was

first called on a Basha inquiry.[13] Subsequently,

she gave evidence before the jury. Given that CM was to give, and gave, evidence

concerning her being sexually assaulted when she was only 13 years of age (she

was aged 21 at the time of giving evidence at trial), and given that she

preferred to give that evidence in a closed court and that the parties were not

opposed to that course, I directed that her evidence on both the Basha inquiry

and before the jury be given in closed court. In particular, having regard to

the embarrassment the witness may feel in giving evidence, in the presence of

the public, of an incident of alleged sexual abuse when she was a child and the

fact that such embarrassment may impinge upon her ability to give that evidence

unencumbered, and thereby may prejudice the administration of justice, I made an

order under s

18 of the Supreme

Court Act that her evidence be heard in closed court.

Ruling No 6: Alleged lies as incriminating conduct

Introduction

107 At the conclusion of evidence, and just before Mr Bourke formally closed the

Crown case, as foreshadowed earlier in the trial, I heard further argument on

the application pursuant to s 23 of the JD Act to rely on three alleged lies in

the accused’s record of interview identified in the notice as evidence of

incriminating conduct. In each case, I refused the application. My reasons for

doing so follow:

Item (c)(i): Did not know if Mr Tascas had taken his vehicle with him to

Bathurst

108 The first alleged lie relied on (set out in item (c)(i) of the notice) was

the accused’s assertion that he did not know if Mr Tascas had taken his vehicle

with him when he went to Bathurst.

109 The Crown relied on the answers to questions 110 and 111 of the interview to

establish the alleged lie:

110 Q: Okay. Do you know how he was getting there [i.e. to Bathurst]?

A: I assumed they were driving, but no, I didn’t know.

111 Q: Did his car go with him?

A: It wasn’t at home the following week. But I don’t know, I don’t – do not know

whether it went with him, I don’t know.

110 For reasons that follow, I found that it was not open to conclude that those

answers contained the alleged lie. First, as will be remembered, it had been

conceded (correctly) by Mr Bourke earlier in the trial that the evidence could

not exclude the reasonable possibility that Mr Tascas did in fact tell Mr Butler

he was going to Bathurst. Secondly, the evidence was not clear as to whether Mr

Tascas’s car was around the week following the Bathurst car races. Thirdly, to

ask a jury to conclude that the accused was lying when he said he did not know