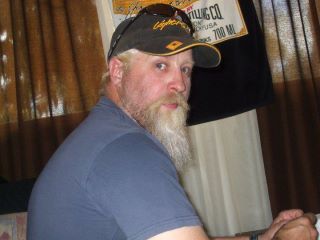

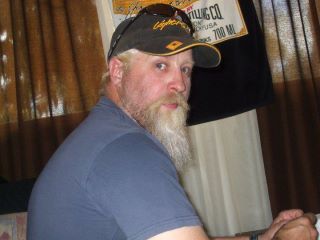

Paul Clifford YORK (Yorky)

Paul Clifford YORK (Yorky)

Paul, if you're reading this, you need to know you are NOT

in any trouble with Police. Sandra really needs you now, please come home.

- Last seen:

Wednesday, 09 November 2011

- Year of birth:

1966

- Height: 177 cm

- Build: Slim

- Eyes: Green

- Hair: Brown

- Complexion:

Fair

- Gender: Male

- Distinguishing

Feature: Thumb missing on left hand, with extensive

scarring on the hand and arm. Scar on forehead. Paul also had a full

beard at time of disappearance

Circumstances

Paul York has not been seen since

Wednesday 9 November 2011 after leaving his home address in Dalwallinu,

Western Australia. He was last seen wearing brown work boots, short blue

“hard yakka” shorts, a t-shirt and flannelette shirt. His white 1992 Holden

utility was found on the 15 November 2011, 17km west of Kalannie at Petrudor

Rocks. Western Australia. Despite an extensive land and air search by

Police, Paul has not been located.

Coroners Act 1996 (Section 26(1))

RECORD OF INVESTIGATION INTO DEATH

I, Barry Paul King, Deputy State Coroner, having investigated the suspected

death of Paul Clifford York with an inquest held at Northam Courthouse on 4

February 2020, find that the death has been established beyond all reasonable

doubt and that the identity of the deceased person was Paul Clifford York and

that death occurred on or about 10 November 2011 at Petrudor Rocks National Park

from an unascertained cause in the following circumstances:

INTRODUCTION

1. Paul Clifford York lived in Kalannie. He was last seen at about 8.00 am on

10 November 2011. He failed to show up for work that day and was not seen again.

2. On 11 November 2011, Mr York’s partner, Sandra Nailer, attended the

Dalwallinu police station and reported that he was missing and that he had

previously spoken of suicide. Police commenced an investigation and, on 15

November 2011, found Mr York’s utility vehicle (ute) in dense bushland in

Petrudor Rocks National Park (Petrudor Rocks).

3. A search was then undertaken in Petrudor Rocks, and further evidence that

was found there suggested that Mr York may have hanged himself, but his body was

not found by the time the search was called off. Not all of the national park

was searched.

4. Police inquiries found no record of Mr York having contacted banks, phone

companies or government agencies since 10 November 2011.

5. Under s 23 of the Coroners Act 1996, where a person is missing and the

State Coroner has reasonable cause to suspect that the person has died and that

the death was a reportable death, the State Coroner may direct that the

suspected death of the person be investigated. Where the State Coroner has given

such a direction, a Coroner must hold an inquest into the circumstances of the

suspected death of the person and, if the Coroner finds that the death of the

person has been established beyond all reasonable doubt, into how the death

occurred and the cause of the death.

6. On 14 August 2018, a report by Detective Senior Constable William Stokeley

pertaining to Mr York’s disappearance was provided to the State Coroner.

7. On 3 October 2018, Mr York’s mother and Ms Nailer asked the principal

registrar of the Coroner’s Court for an inquest to be held into Mr York’s

disappearance.

8. On 29 October 2018, the State Coroner directed that the suspected death of

Mr York be investigated.

9. On 4 February 2019, I held an inquest at the Northam Coroner’s Court into

Mr York’s suspected death. The documentary evidence at the inquest comprised a

brief of evidence which included the report by Detective Senior Constable

Stokeley and other relevant material.1

10. Detective Senior Constable Stokeley provided oral evidence, as did:

a. Carol Linda Ridgway, a volunteer ambulance driver;

b. Jonathan Paul Draffin, a business owner who employed Mr York from 2007 to

2011;

c. Matthew Thomas York, Mr York’s youngest brother;

d. Sergeant Paul William World, the officer in charge of the Dalwallinu

Police Station in 2011; and

e. Grant Ashley Evans, an old friend of Mr York .

11. I have found that the death of Mr York has been established beyond all

reasonable doubt, but I have not been able to find how death occurred or the

cause of death.

PAUL CLIFFORD YORK

12. Mr York was born on 27 June 1966 in Dalwallinu, so he was 45 years old

when he disappeared.

13. He grew up in Dalwallinu with his parents and three brothers. 8 His older

brother died in a car accident in 1977, which deeply affected Mr York.

14. Mr York generally presented as a happy and funny person who would do

anything for his friends and family. He made a few close mates in Dalwallinu and

kept them over the years. 10 He was a good worker and was capable of undertaking

work in different trades though he was not qualified in any trade.

15. Mr York married in his early 20s, but the marriage only lasted a few

years. The break up was difficult for him and he ‘went off the rails’. 12

Following the split with his wife, he was at a party when he ignited acetylene

in an oil drum and caused an explosion in which he lost his left thumb and

sustained scarring on his left arm and forehead. At around this time, he also

began self-harming by cutting himself with razor blades.13

16. In about 2002, Mr York went to Laverton and then lost touch with his

family and friends for a few years. They understood that he was doing various

jobs in South Hedland and Karratha. During this time, he became involved with

drug use and was jailed for six months in relation to several burglaries. He was

released in December 2007 and went to live with his mother before moving in with

a friend.14 Shortly after that, he moved in with a girlfriend and lived with her

in Dalwallinu until they broke up in 2009.

17. Mr York worked in several manual and labouring jobs under his own

company, Dalwallinu Technical Services, and in 2007 he began working for a

company called Hut City Portables.

18. On about 21 October 2009, Mr York called his boss at Hut City Portables,

Mr Draffin, and said that he was tied up in a tree in Petrudor Rocks and that he

was going to end his life. Mr Draffin told him not to be stupid and to come to

see him to talk about it. About 15 minutes later, Mr York arrived in Kalannie

from the direction of Petrudor Rocks and went to see Mr Draffin. He was crying

uncontrollably. Mr Draffin was worried about him, so he took him to Goomalling

to see a GP, Dr Nina McLellan.

19. Mr York told Dr McLellan that he had attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder (ADHD) from an early age and that he had been sexually abused by a

priest, but that he had managed to obtain a degree. He said that he had

depressed mood, low self-esteem, suicidal thoughts, panic attacks and irrational

fear. Dr McLellan prescribed mirtazapine and alprazolam.19 Mr York returned to

work and seemed okay after that.

20. In around 2010, Mr York moved to Kalannie and met Ms Nailer. They became

a couple and lived together until he disappeared. Mr York drank beer most days

after work, and he smoked cannabis when stressed, but he and Ms Nailer were

getting on fine and were planning to get married once they could get some money

together. In 2011, Ms Nailer became pregnant, with the baby due to be born on 17

January 2012.

21. Mr Draffin had to lay off Mr York in about 2011 when the Hut City

Portables business was not doing well. Mr York began doing ad hoc work for an

electrician in Kalannie. He sustained a knee injury while working and required

time off work because of the pain

22. In about May 2011, Mr York told Mr Draffin’s wife, Brenda Fawkes, that he

would kill himself at Petrudor Rocks and that he knew the area and that his body

would not be found.

23. As noted, Mr York’s mental health history included depression, self-harm

and suicide ideation (by hanging), and he had previously attempted suicide by

amphetamine overdose and by hanging. His medical records indicate reported

sexual abuse, unconfirmed ADHD, substance abuse, anxiety, stress and depression.

He had sought medical help in relation to his mental health in the past and had

been prescribed medication.

EVENTS LEADING UP TO MR YORK’S DISAPPEARANCE

24. About a week before his disappearance, Mr York was in contact with his

neighbour, Michael Kerr, who gave him some of his prescription pain medication.

At the time, Mr Kerr felt that Mr York was also having major psychological

problems.

25. On 1 November 2011, Mr York went to Mr Kerr’s house in a distressed

state, so Mr Kerr drove him and Ms Nailer to the Moora Health Centre26 where Mr

York saw Dr Judy Kimani. Mr York reported a history of sexual abuse as a

teenager, a nervous breakdown and a previous suicide attempt, including a recent

attempt to hang himself at home when Ms Nailer had intervened.

26. Mr York also told Dr Kimani that he was using alcohol and cannabis

regularly to escape his symptoms and that, if he were to go home, he could

commit suicide. With Mr York’s consent, Dr Kimani arranged for him to be

transferred to the Joondalup Health Campus (JHC) by ambulance that afternoon for

urgent psychiatric assessment and management.

27. During the two-hour ambulance trip from Moora to JHC, Mr York was calm

and talkative. He told the volunteer ambulance officer, Carol Ridgway, that he

made amphetamines and supplied drugs to bikies, that he did not want to be a

father and that he was being verbally abused at work. He told her that being

sexually abused had ruined his life and that was why he was depressed all the

time and wanted to kill himself.

28. Mr York also told Ms Ridgway that he had a plan about how he would kill

himself and, when he did it, his body would not be found. He said that he could

not cope anymore and that he knew what to say so that he would get out of

hospital.

29. When he arrived at JHC, Mr York sent a message to Ms Nailer to say that

he was there and was safe.30 He was assessed in the emergency department (ED) by

a psychiatric liaison nurse and was then examined by Dr Salawa Michail, a

psychiatric registrar.

30. Dr Michail gained the impression that Mr York had suicidal ideation in

the context of ongoing severe psychosocial stressors on a background of possible

adjustment disorder and major depression episode, comorbid personality structure

(cluster B personality trait) and poor coping skill. Dr Michail considered that

Mr York was at a low-to-moderate risk of selfharm.

31. With Mr York’s input, Dr Michail made a plan to admit Mr York to an open

ward in the JHC mental health unit (MHU) for containment and further assessment.

If he were to be settled by the next morning, he could be discharged home with

community mental health service review, but if he was still agitated and

suicidal, he could be admitted into the MHU.

32. As there were no vacant beds available in the MHU, Mr York stayed in the

ED for containment and assessment the next morning.

33. On 2 November 2011, Dr Michail reviewed Mr York and found that he had

restricted affect and was feeling low and stressed, with suicidal thoughts. He

could not trust himself to leave hospital. There were still no beds available,

so Mr York remained in the ED and Dr Michail prescribed the antidepressant

desvenlafaxine. Mr York continued to message Ms Nailer while he was at

JHC.

34. When Dr Michail assessed Mr York on the morning of 3 November 2011, Mr

York reported having had a good night sleep and still feeling depressed, but

denied any self-harm thoughts. He requested to go home so that he could go back

to work and be with Ms Nailer. Mr York was discharged to the care of Ms Nailer

with sufficient medication to last one week, and a follow-up was arranged at

Wheatbelt Mental Health Service (WMHS).

35. After leaving hospital Mr York was ‘quite dopey’ due to his medication,

but he improved after a few days. He did not talk of self-harm, and he still had

a job that made him happy.

36. On 7 November 2011, a triage officer from WMHS tried unsuccessfully to

call Mr York.

37. On 9 November 2011, a member of the WMHS team spoke to him by phone. Mr

York reported that he was just getting by and that he was on the go all the

time, was not sleeping well, and could not cope in that state. He asked to try

dexamphetamine, which he had previously taken illegally, and he was told that he

would require a referral to a private psychiatrist. He was happy to see the WMHS

team on their next visit to Kalannie. He said he was working for an electrical

contractor and that Ms Nailer was a protective factor. He also said that he was

drinking eight full-strength beers and using two grams of tetrahydrocannabinol a

day, but that he was not using amphetamine

38. The WMHS team member completed an Adult Brief Risk Assessment form and

found that Mr York was at moderate risk of both suicide and violence against

others.

39. Also on 9 November 2011, Mr York was driving in Kalannie when he saw an

old friend, Grant Evans, walking down the street. He stopped for a chat and then

drove Mr Evans to Ashley Waters’ house, where Mr Evans was staying. Mr York

seemed to Mr Evans to be fine and pretty happy.

40. Mr York stayed at Mr Waters’ house for a while and had a cigarette. He

left for a few hours and returned with a bag of shopping for Mr Evans. He, Mr

Evans and Mr Waters drank some beers and Mr Evans had a chat with Mr York about

his new job with the electrician. Mr York then left.

41. In the evening, Mr York did up some accounts in relation to work he had

completed. He seemed fine to Ms Nailer and he seemed to be looking forward to

the future. He and Ms Nailer went to bed after midnight.

42. Early on 10 November 2011, Mr York and Ms Nailer had coffee together

before Mr York left to go to work at the electrician’s shed. At around 6.30 am

Mr York called Mr Evans, who was at the Rolinson Farm where he was working, and

said that he was going to bring Mr Evans’ shopping to him.

43. Mr York arrived at the Rolinson Farm in his ute shortly after the call

and dropped off the shopping, which was a bottle of cordial. He then had a brief

chat with Mr Evans, Peter Rolison and Keith Rolison, who were standing together.

Keith Rolison commented on a ladder in Mr York’s ute. Mr Evans thought that Mr

York was not quite as happy as he had been the previous evening and that he

seemed a little bit quiet. Mr York left, saying that he was heading for work.

This was the last time Mr York was seen

44. At around lunch time, Ms Nailer called Mr York and asked him if he would

be coming home for lunch. Mr York said no, and that he would see Ms Nailer

later. Mr York did not return home that night and did not answer any of Ms

Nailer’s phone calls. Ms Nailer’s phone call was the last known contact with Mr

York.

SEARCH FOR MR YORK

45. On Friday 11 November 2011, Ms Nailer was concerned that Mr York had not

returned home. After several unsuccessful attempts to contact him, she went to

the Dalwallinu Police Station and reported that he was missing.

46. Dalwallinu Police and Wheatbelt detectives commenced investigations that

day, including metropolitan and state wide missing persons broadcasts.

47. On the morning of 15 November 2011, Ms Fawkes informed Sergeant World

about Mr York speaking to her six months earlier and telling her that he would

kill himself in Petrudor Rocks.

48. Sergeant World went to Petrudor Rocks with two other police officers and,

by chance, located Mr York’s ute on a firebreak track on the southeast corner of

the national park. An extensive search and rescue operation was then commenced

under the direction of the WA Police Emergency Operations Unit. It involved 12

other business units, including Northam and Moora State Emergency Services (SES)

and the police air wing, 50 with more than 100 people assisting.

49. On 16 November 2011, a triangulation conducted on Mr York’s phone

indicated that it had been turned off on 8 November 2011. Other evidence

suggests Mr York used his phone on the 9 November 2011 and 10 November 2011, but

there is no evidence to establish that he used his phone after that.

50. On 18 November 2011 a search team found a ladder about 800–1000 metres

north of Mr York’s ute. Broken tree branches were observed over two metres above

the ground in a direct path from Mr York’s ute to where it was found, indicating

that Mr York had carried the ladder there.

51. Sergeant World said that, as the searchers moved north towards extremely

dense bushland, they noticed a dead tree that had been broken. They then found a

40 meter length of rope, which led them to surmise that the tree had been tested

to see if it would bear weight.55 The searches also found some tape which, like

the ladder and the rope, was identified as coming from Mr York’s ute.

52. The area northeast of the ladder was considered to be an area of high

probability for finding Mr York, but as the search teams moved further towards

the northeast quadrant of Petrudor Rocks, the vegetation became increasingly

more dense. Search teams of 10 personnel were taking up to eight hours to search

an area of 600 metres by 15 metres.

53. On 20 November 2011, the search was scaled down in order to re-deploy the

SES staff to bush fires and because of the fire risk and the dense conditions in

and around the search area. On 24 November 2011, the search was suspended until

4 and 5 December 2011.

54. On 30 November 2011, Sergeant World wrote to the Wheatbelt District

Police Office, stating that it was believed that Mr York was located somewhere

in the national park reserve, and that the initial search covered approximately

three quarters of the park, leaving approximately nine square kilometres to be

searched. He requested completion of the search and set out what would be

required.

55. Due to weather conditions and the unavailability of SES personnel, the

search was delayed until 3 January 2012 when it was undertaken with limited

numbers. The search did not cover all of the remaining area, leaving a sizeable

area unsearched. No further trace of Mr York was uncovered. It was decided that

the remaining three or four square kilometres would not be searched unless

further information came to hand.60

FURTHER INVESTIGATIONS

56. On 17 November 2011, Dr Paul Luckin, an expert in survival time-frames in

search and rescue scenarios, spoke with police and advised that he was not

willing to estimate Mr York’s time of survival from the information available.

However, he said that the medication that Mr York was prescribed could add to

suicidal tendencies, that self-harm was likely, and that it was unlikely that Mr

York was lost or that he wanted to be found. Dr Luckin agreed that Mr York would

have been capable of walking from the search area into an area of safety or

rescue.

57. Police issued a state-wide broadcast and a media release about Mr York’s

disappearance, and Ms Nailer set up a Facebook page. Police received several

reports of persons looking like Mr York and of speculations from the community

about his whereabouts. However these were unsubstantiated and did not produce

further lines of inquiry.

58. On 29 February 2012, the investigation into Mr York’s disappearance was

transferred to the Missing Persons Team and he was added to the National Missing

Persons Register.

59. Further investigations confirmed that, from the date of Mr York’s

disappearance to July 2018:

a) Mr York made no claims by under the Medical and Pharmaceutical benefits

Scheme;

b) no certificates had been received by the Registry of Births, Deaths and

Marriages to show his death or change of name;

c) Centrelink had no record of any contact with him;

d) the Department of Immigration and Boarder Protection’s records indicate

that he had not left Australia;

e) he had not used any of his bank accounts since 9 November 2011, or his

superannuation account since 21 February 2011;

f) the Australian Federal Police and missing persons units in all states had

no contact with him;

g) there were no unidentified bodies or remains at the State Mortuary which

could have been his;

h) the Department of Corrective Services had no records of him being in

custody;

i) there had been no activity on Mr York’s mobile phone number though it has

not been disconnected; and

j) he not been seen or been in contact with any person in the Dalwallinu area

since 10 November 2011.

60. Detective Senior Constable Stokely concluded that all possible avenues of

investigation had been exhausted.

CONCLUSION AS TO WHETHER DEATH HAS BEEN ESTABLISHED

61. The following factors point to the likelihood that Mr York is dead:

a) Mr York’s mental health history of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation

and suicide attempts, including by hanging and overdose;

b) his recent acute suicidal ideation;

c) his aborted suicide attempt by hanging in Petrudor Rocks in 2009;

d) his previous indication to Ms Fawkes that he intended to end his life in

Petrudor Rocks and that his body would not be found;

e) the harsh and remote environment in which he apparently disappeared;

f) that his ute was left in a place that was difficult to find;

g) the difficulty in searching Petrudor Rocks and the fact that the area in

which he was most likely to have died was not searched

h) his lack of contact with his friends or family, including his child;

i) his lack of contact with banks and government agencies; and

j) the lack of reliable sightings of Mr York.

62. There was speculation that Mr York had disappeared and faked his death in

order to avoid the responsibilities of being a father, but that evidence was not

substantiated by reference to statements made by Mr York to that effect. An old

friend of Mr York’s, Paul Colgate, said that Mr York was ‘shocked’ to learn that

Ms Nailer was pregnant because he had always understood that could not have

children, but Mr Evans said that Mr York was ‘surprised’ rather than shocked,

that he did not seem unhappy, and that he did not say that he did not want a

child.

63. Ms Nailer said that Mr York was very excited about being a father and

would tell everyone.

64. Mr York’s brother, Matthew York, said that he never thought that Mr York

had run away because of a child; he spoke about being excited about having a kid

and you could see it in his eye that he was looking forward to it.

65. As to the question of whether Mr York was dead, Matthew York said that he

had initially thought that Mr York was alive, but after hearing of Mr York’s

mental health issues and attempted suicide, he was no longer certain.

66. There were also people who had suggested to investigators that Mr York

had been murdered or that he disappeared due to his involvement with drugs and

gangs. These people either refused to provide statements, declined to sign draft

statements or proved subsequently uncontactable, and there was no other

evidence to suggest any criminality in Mr York’s disappearance.

67. While there is no direct evidence to prove that Mr York is dead, I am

satisfied on the basis of the information available that Mr York’s death has

been proven beyond all reasonable doubt.

68. On balance, I am satisfied that Mr York died at Petrudor Rocks National

Park on or about 10 November 2011.

THE CAUSE OF DEATH AND HOW DEATH OCCURRED

69. The evidence indicated that the most likely circumstances surrounding Mr

York’s death involved Mr York walking away from his vehicle in Petrudor Rocks

National Park into dense bush where he died.

70. However, it is not possible to determine the cause of death since he

could have ended his life by hanging himself, overdosing on prescription

medications, or other means.

71. It is also not possible to rule out an accidental death, since Mr York

may have inadvertently had a fatal accident, or he may have been bitten by a

venomous snake.

72. I am therefore unable to find the cause of death or how death occurred.

CONCLUSION

73. Mr York was a well-liked friend and co-worker, who enjoyed his working,

social and private life. He had a loving partner and was soon to be a father for

the first time.

74. However, he had also struggled with drug abuse, depression, self-harm and

suicide ideation from a relatively young age.

75. While the evidence does not provide certainty in relation to a cause of

death, there is no reasonable doubt that he is dead.

B P King

Deputy State Coroner

8 October 2020

WA POLICE are searching for a man who has been missing in the

Wheatbelt for a week.

Paul Clifford York, 45, was last seen in the town of Kalannie last

Thursday at 7am and was reported missing the next day.

His white 1992 Holden utility was found on Monday morning 17km west of

Kalannie at Petrudor Rocks.

Police and SES are searching a 9-square kilometre area near Petrudor Rocks,

which is a popular picnic spot off the Pithara-Kalannie Road.

Mr York is described as 168cm tall with a slim build, short brown hair,

green eyes and a beard.

He has a thumb missing from his left hand.

He was last seen wearing brown work boots, short blue Hard Yakka shorts, a

t-shirt and a flannelette shirt.

Anyone with information is asked to contact Crime Stoppers on 1800 333 000.