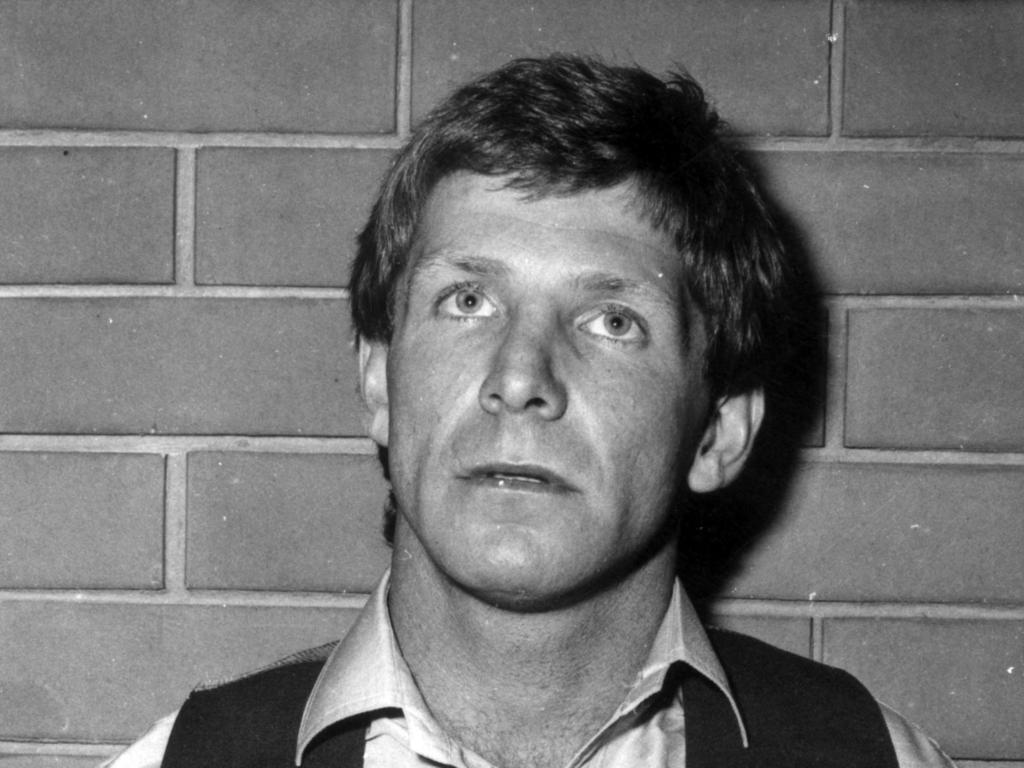

Laurence "Laurie" Joseph PRENDERGAST

IN THE CORONERS COURT

Court Reference: COR 2018 1328 OF VICTORIA AT MELBOURNE

FINDING INTO DEATH WITH INQUEST

Form 37 Rule 63(1) Section 67 of the Coroners Act 2008

Findings of: Caitlin English, Deputy State Coroner

Deceased: Laurence Joseph Prendergast

Delivered on: 17 December 2021

Delivered at: Coroners Court of Victoria, 65 Kavanagh Street, Southbank

Hearing date: 1 October 2021

INTRODUCTION

1. Laurence Joseph Prendergast was born on 5 July 1950. He was aged 35 when he was reported as a missing person by his wife, Ursula Prendergast, on 25 August 1985.

2. Mr Prendergast was last seen alive on 23 August 1985 driving his silver 1982 Volvo sedan on Brogil Road, Warrandyte.

3. At the time of his disappearance Mr Prendergast lived on Brogil Road, Warrandyte, with his wife, Ursula, their daughter, Lauren, and his stepchildren, Carl and Kylie, from Mrs Prendergast’s previous marriage.

4. He has never been heard from since by either family or friends.

5. Despite extensive searches by police, Mr Prendergast’s body has never been located and he is presumed to be dead. All efforts to locate him have been unsuccessful and there have been no ‘proof of life’ indicators since his disappearance.

THE PREVIOUS CORONIAL INVESTIGATION

6. In or about November 1986, Mrs Prendergast made an application to Court to conduct an inquest into her husband’s alleged death the pursuant to the Coroners Act 1985 (the 1985 Act) and an inquest was subsequently conducted on 29 October, 9 November, and 20 November 1990.

7. On 29 November 1990, Coroner Gurvich delivered a written finding in which he determined that the evidence before him did not satisfy him that Mr Prendergast was deceased. He noted that there could be a number of reasons that could explain his disappearance other than death.

8. Coroner Gurvich found that before finding a person was deceased, there needed to be evidence of a convincing nature. Based on the evidence set out below, he was satisfied that it strongly suggested that until his disappearance Mr Prendergast lived a life of crime and deception and fraternised with persons who led similar lives. He described Mrs Prendergast’s evidence as of little value as it was unclear whether her evidence was truth or fiction. However, he accepted she was genuinely concerned for her missing husband.3

9. Coroner Gurvich found that the evidence was suggestive that Mr Prendergast had a “strong incentive” to disappear. But on the evidence, he was neither satisfied that he had planned his disappearance nor was deceased. He referred to the possibility that the unusual financial transactions before his disappearance pointed to his making arrangements for his disappearance.

10. Coroner Gurvich noted the investigative powers of 1985 Act appeared to be confined to matters relating to reportable deaths and fires in the circumstances described in that Act. ‘Death’ was defined to include a suspected death. A ‘reportable death’ had various meanings and Coroner Gurvich accepted that it fell into category (d), being a death of a person who ordinarily resided in Victoria at the time of death.

11. However, he noted that all the inquest had established was that Mr Prendergast was a person who ordinarily resided in Victoria – but not that he had resided so at the time of his death as his death had not been established. He further set out the applicable sections of the 1985 Act, including the findings that he was required to make – all of which referred to a death having occurred. Given that he was unable to conclude that Mr Prendergast was deceased, he could not make any findings and therefore determined that he had no jurisdiction to further pursue the matter at the time.

12. A transcript of the evidence from the 1990 inquest and Coroner Gurvich’s decision have been available to me in completing this finding.

THE CURRENT CORONIAL INVESTIGATION

Application to re-open the coronial investigation

13. On 8 January 2018, Mrs Prendergast submitted a Form 43 Application to Set Aside Finding pursuant to section 77 of the Coroners Act 2008 (the 2008 Act). Her reasons for application were as follows: My children and I, would like to put a “memorial” in a cemetery in Templestowe, for Laurie. My husband disappeared on the 22/8/1985, and has not be [sic] seen of heard of since. The coronial inquiry in 1990, had an “open finding”, and I would request that my husband be declared as “deceased”, considering the 32 years in question, & that the coronial decision was made, in view of his apparent disappearance, and circumstances at the time. The Police have recently advised, that they now believe he is “deceased”, he was connected to the underworld war in 1979.

14. At that time the State Coroner, Judge Sara Hinchey, formed the preliminary view that she may not have jurisdiction to hear the application because the finding into Mr Prendergast’s death was made under the 1985 Act, which was repealed when the 2008 Act came into operation on 1 November 2009. It happened that a number of other parties found themselves in a similar situation and so Directions Hearings were held on 30 January and 27 February 2018 to hear submissions. Victoria Legal Aid made submissions on behalf of Mrs Prendergast.

15. Judge Hinchey accepted the submission made by on behalf of Ms Prendergast that the decision of Coroner Gurvich made pursuant to section 15(1) of the 1985 Act was not an investigation for the purposes of section 77 of the 2008 Act. Counsel proposed that Mrs Prendergast make a fresh report concerning her husband’s suspected death. And so, on 27 February 2018 Judge Hinchey formally dismissed Mrs Prendergast’s section 77 application.

16. On 16 March 2018, Detective Leading Senior Constable Peter Towner formally reported the suspected death of Mr Prendergast by submitting a Form 83 Police Report of Death for a Coroner and prepared a coronial brief.

17. In August 2018, Judge Hinchey directed this matter should proceed to summary inquest. The investigation was transferred to Coroner Rosemary Carlin in March 2019. In September 2019, Coroner Carlin was appointed to the County Court and I took over carriage of this matter.

The Coroners Act 2008

18. Under the 2008 Act, coroners independently investigate ‘reportable deaths’ to find, if possible, identity, cause of death and, with some exceptions, surrounding circumstances.6 Cause of death in this context is accepted to mean the medical cause or mechanism of death. Surrounding circumstances are limited to events which are sufficiently proximate and causally related to the death.

19. Broadly, reportable deaths are deaths that are unexpected, unnatural or violent or have resulted, directly or indirectly, from an accident or injury. ‘Death’ is defined to include suspected death. As his body has never been found, Mr Prendergast’s death is a suspected death.

20. The jurisdiction of the Coroners Court of Victoria is inquisitorial. The Act provides for a system whereby reportable deaths are independently investigated to ascertain, if possible, the identity of the deceased person, the cause of death and the circumstances in which death occurred.

21. It is not the role of the coroner to lay or apportion blame, but to establish the facts. It is not the coroner’s role to determine criminal or civil liability arising from the death under investigation, or to determine disciplinary matters.

22. The expression “cause of death” refers to the medical cause of death, incorporating where possible, the mode or mechanism of death.

23. For coronial purposes, the phrase “circumstances in which death occurred,” refers to the context or background and surrounding circumstances of the death. Rather than being a consideration of all circumstances which might form part of a narrative culminating in the death, it is confined to those circumstances which are sufficiently proximate and causally relevant to the death.

24. The broader purpose of coronial investigations is to contribute to a reduction in the number of preventable deaths, both through findings and the making of recommendations.

25. All coronial findings must be made based on proof of relevant facts on the balance of probabilities. In determining these matters, I am guided by the principles enunciated in Briginshaw v Briginshaw. 13 The effect of this and similar authorities is that coroners should not make adverse findings against, or comments about individuals, unless the evidence provides a comfortable level of satisfaction that they caused or contributed to the death.

The current coronial investigation

26. After submitting the report of Mr Prendergast’s death, a renewed coronial investigation was undertaken on behalf of the coroner by a member of Victoria Police who was appointed as the coroner’s investigator. Detective Leading Senior Constable Towner compiled a coronial brief, which was submitted on 15 May 2018. It details the ‘proof of life’ checks that have been conducted.

THE INQUEST

27. I conducted an inquest on 1 October 2021 and heard evidence from Mr Peter Towner (now retired) and Detective Senior Constable Candice Robson from the Missing Persons Squad regarding the course of the coronial investigation. Upon Mr Towner’s retirement from Victoria Police, Detective Senior Constable Robson took over the role as coroner’s investigator.

28. In light of the COVID pandemic, and the Coroners Court Practice Direction 2/2021 regarding court proceedings, the Inquest was a hybrid hearing with witnesses appearing remotely by video link, and Mr Prendergast’s wife and daughter Lauren and other family members watching remotely.

CIRCUMSTANCES IN WHICH THE DEATH OCCURRED PURSUANT TO SECTION 67(1)(c) OF THE ACT

29. Mr and Mrs Prendergast married in May 1981. Together they had one child, Lauren. Mrs Prendergast’s children from a previous marriage, Carl and Kylie, also lived with them.

30. At the time of the first coronial investigation, Mrs Prendergast described her husband as a “professional punter”, but his sister, Jane Prendergast, described her brother as an “infamous criminal” who made his money from criminal activities. Indeed, there is evidence that Mr Prendergast was convicted of various serious offences. It was said that he lived in constant fear of being murdered. While Mrs Prendergast acknowledged her husband “had had trouble with the police” before they commenced their relationship, she noted that after their relationship began Mr Prendergast turned a new leaf, putting his past behind him. She said they kept to themselves and it was rare that they fraternised with his old associates.

31. In late 1982 or thereabouts, the family moved to Brogil Road in Warrandyte. Coroner Gurvich noted that the property was registered in the name of ‘David Carter’ – an alias for Mr Prendergast.

Events proximate to Mr Prendergast’s disappearance

32. During July 1985 or thereabouts Mr Prendergast obtained a passport, which, according to Mrs Prendergast, was for the purpose of an overseas family holiday.

33. On 9 August 1985, the Brogil Road property was transferred to Mrs Prendergast under the signature of ‘D. Carter’. Mrs Prendergast explained that the property was transferred to her at the time so they could sell it and borrow money as they were experiencing financial difficulties. A pool was also being installed for the purposes of the sale. It appears that it was thought the sale would be better facilitated if the property was registered in Mrs Prendergast’s name given the house had previously been the subject of a raid.

34. On 15 August 1985, Mrs Prendergast borrowed $6,000, which she received by way of a cheque. On Mr Prendergast’s instructions, she cashed the cheque and gave him the proceeds. She apparently did not know what he was going to do with the money.

35. On the same day, Mrs Prendergast travelled to Queensland with her daughter, Lauren, to visit her parents – a trip that was described as one on the “spur of the moment”. She explained that her husband did not accompany them as he had a fear of flying.

36. During Mrs Prendergast’s Queensland trip, her son, Carl, had remained with Mr Prendergast. Kylie stayed with her father. Carl was aged 13 years at the time.

37. On 17 August 1985, Mr Prendergast met up with his cousin, William (Bill) Prendergast. They apparently had not been on close terms for many years until several months before Mr Prendergast’s disappearance. They had a coffee and talked about various things. He invited William’s son, Sean, to stay the night.

38. Carl reported that he saw Mr Prendergast with two other men in addition to William Prendergast, however it is not entirely clear whether he was describing the meeting of 17 August. Carl said that Mr Prendergast had a brown paper bag, which he thought was full of money, at the time.

39. The next morning, 18 August 1985, Mr Prendergast told Carl that he had gone out the previous night and arrived home at 4.00am. They did not discuss the reason for his outing.

40. Later that morning, Mr Prendergast returned Dean to his cousin’s home. William Prendergast never saw or spoke with his cousin again.

41. At about 5.00pm on 22 August 1985, Mrs Prendergast spoke to her husband on the telephone. He sounded to be in good spirits. Mrs Prendergast told her husband that she would speak to him the next night and let him know her flight, which depended on seat availability. That was the last time Mrs Prendergast spoke to her husband. She never saw him again.

42. That evening, Mr Prendergast took Carl to a pizza parlour with two friends.

43. On 23 August 1985, Carl and Mr Prendergast cleaned the house in anticipation of Mrs Prendergast returning home the next day. It was Mr Prendergast’s usual habit to go to the shops in the morning to buy a newspaper, but Carl could not remember whether he did so that morning. Later that morning at about 10.30am, he drove Carl to Doncaster Shopping Town. Carl recalled Mr Prendergast to be in good spirits. Mr Prendergast requested that he return home by 4.00pm.

44. John Roe, a builder undertaking work at a nearby property on Brogil Road, stated that he saw a person believed to be Mr Prendergast leave home alone in a Volvo at approximately 7.30am and saw him return about 30 minutes later. Upon his return, Mr Roe spoke to him, asking whether he could use his driveway to run a hose from a compressor, to which the man agreed. Mr Roe stated that the man and a boy then left at 10.30am and the man returned alone about 30 minutes later. Mr Roe later saw the man leave again later in the afternoon at about 2.30pm; he was alone and in the Volvo.

45. Mr Roe also recalled seeing a Volkswagen Kombi van parked in Brogil Road, which had ‘Prendergast’ printed on the side, on the same morning. Coroner Gurvich was satisfied that the van belonged to William Prendergast, who was adamant he was not at the Prendergast home on 23 August 1985. It was claimed that William Prendergast had removed his name from the side of the van before his cousin disappeared but there was discrepancy in the evidence as to when this had occurred. Coroner Gurvich was satisfied that it was William Prendergast’s van at or near his cousin’s home on the day of his disappearance.

46. At 3.45pm, Carl arrived by bus at the Warrandyte Bridge and stopped at a phone box to telephone home to see if Mr Prendergast could give him a lift home – this was their usual arrangement. If no one answered, he would proceed to walk home alone. There was no answer.

47. Carl arrived home at approximately 4.15pm. The door was locked, and nobody was at home. He observed two unwashed plates and two cups in the kitchen sink, which had not been there in the morning.

48. At approximately 5.00pm, Mrs Prendergast rang, and Carl reported that Mr Prendergast was not home. She thereafter continued to telephone hourly, concerned that her husband was not at home. She arranged for someone to look after Carl and began telephoning Mr Prendergast’s associates to enquire about his whereabouts. Mr Prendergast never returned home.

49. At approximately 5.30pm that day, a witness observed Mr Prendergast’s Volvo parked in Cartmell Street, Heidelberg. This was subsequently reported to police on 27 August.

50. Mrs Prendergast returned home on the evening of 24 August 1985. She explained that she was unable to arrange an earlier flight, but Coroner Gurvich was satisfied that there was at least one earlier available flight. She explained that she had initially thought her husband was “being held incommunicado by the police”, which Coroner Gurvich noted may have explained her lack of urgency in returning home.

51. At 1.30am on 25 August 1985, Mrs Prendergast reported her husband missing to police. She attended the Hampton Criminal Investigation Branch accompanied by her solicitor. Coroner Gurvich’s finding notes the following about this event:

(a) Mrs Prendergast refused to reveal her address on the apparent advice of her solicitor;

(b) she reported that she feared her husband had been killed by criminals. However, in evidence she denied she believed this;

(c) in evidence Mrs Prendergast stated she believed her husband may have been in the custody of Federal Police. However, by the time of her police report, she did not believe that to be the case as she had conducted enquiries; and

(d) it had been previously arranged that her husband was to pick her up from the airport on the evening of 23 August. However, in evidence Mrs Prendergast did not refer to any such arrangement.

52. Police subsequently examined the Volvo and found there was nothing to indicate foul play. The interior was found to be generally clean throughout with no signs of disturbance.

53. Coroner Gurvich found this report was somewhat flawed because it failed to take into account a cigarette butt found in the car and the fact that Mr Prendergast did not smoke and did not like people smoking in his car. Later, Mrs Prendergast found blonde hairs, a footprint, saliva and blood stains, and grass in the boot. None of these had been found by the police forensic investigator and Mrs Prendergast did not report her findings to police at the time. Coroner Gurvich therefore found Mrs Prendergast’s evidence regarding her findings unsatisfactory. Putting the cigarette butt to one side, Coroner Gurvich noted that it was extremely unlikely that the forensic investigator had failed to notice the items Mrs Prendergast said she found.

54. There was also reference to a silver pistol, which Mr Prendergast kept in his possession when he felt threatened. In the month before his disappearance, Mr Prendergast would take the pistol with him whenever he left the home. However, after he disappeared Mrs Prendergast found the pistol, which indicated to her that he had left home not on his own accord or that he had gone to meet someone with whom he felt safe. Mrs Prendergast subsequently gave the pistol to an unnamed person, and police were unable to verify her account.

55. On 11 December 1985, the mortgage to the Brogil Road property was varied – the mortgagee increased the principal sum from $55,000 to $65,000. David Carter was still listed as the mortgagor and Mrs Prendergast the guarantor. At the coronial inquiry, Mrs Prendergast declined to provide evidence as to whether her husband had signed the document on the grounds that it could incriminate her. Coroner Gurvich was satisfied that it was likely that the document was signed after Mr Prendergast’s disappearance on 23 August 1985 but could not say by whom.

The previous police investigation

56. On 25 August 1985 a missing person report was completed by Constable Glenn Davies who made initial enquiries relating to Mr Prendergast’s disappearance.

57. On 26 August 1985 Sergeant Maxwell Drake took carriage and conducted an investigation, which included speaking with Mrs Prendergast and a number of Mr Prendergast’s associates.

58. In October 1985, a Missing Persons Circular with Mr Prendergast’s photograph was circulated. Sergeant Drake noted that he sought the assistance of the media to publicise the disappearance in the hope that a member of the public would come forward with information.

59. Sergeant Drake also made enquiries in South Australia, New South Wales, and Queensland, which did not elicit any further information. While a number of theories were put forward for the reasons for Mr Prendergast’s disappearance, Sergeant Drake was unable to find any evidence to support any of the theories. He noted that because of Mr Prendergast’s criminal associates, many people may have had a motive to kill him.

60. At the time of the first inquiry into Mr Prendergast’s disappearance, Coroner Gurvich acknowledged that at least one of the investigating police members had received threats in connection with the investigation. However, Coroner Gurvich was satisfied that a thorough and exhaustive investigation of Mr Prendergast’s disappearance had been conducted.

61. The date of the missing person’s report subsequent to Mr Prendergast’s disappearance meant a forensic examination of the scene, namely Mr Prendergast’s house, was not possible.

62. Although there have been a number of reports to police over the years alleging various people were responsible for Mr Prendergast’s death, no person has ever been charged in relation to his death. The current police investigation – ‘proof of life’ checks

63. Detective Leading Senior Constable Towner submitted a coronial brief setting out the extensive ‘proof of life checks’ he has undertaken. Each of these have failed to elicit evidence that Mr Prendergast was alive after his disappearance on 23 August 1985. These included checks with:

(a) Medicare (the Commonwealth Department of Human Services);57

(b) the Australian Passports Office (the Commonwealth Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade);58

(c) the Australian Border Force;59

(d) the Commonwealth Department of Home Affairs;60

(e) the Australian Taxation Office;61

(f) the Victorian Office of Births, Deaths, and Marriages;

(g) VicRoads;63

(h) the Victorian Electoral Roll;64

(i) New South Wales Police;65

(j) the New South Wales Office of Births, Deaths, and Marriages;66

(k) Queensland Police;67

(l) the Queensland Office of Births, Deaths, and Marriages;68

(m) Northern Territory Police;69

(n) the Northern Territory Office of Births, Deaths, and Marriages;7

(o) Western Australia Police;71

(p) the Western Australia Office of Births, Deaths, and Marriages;72

(q) the South Australian Police;73

(r) the Tasmanian Police;74

(s) the Tasmanian Office of Births, Deaths, and Marriages;75

(t) the Australian Capital Territory Police;76

(u) Westpac bank;77

(v) Bankwest bank;78

(w) ANZ bank;79

(x) National Australia bank;80

(y) Commonwealth bank;81

(z) Colonial First State bank;82

(aa) Bendigo and Adelaide bank;83

(bb) HSBC bank;84

(cc) Suncorp bank;85

(dd) ING bank;8

(ee) Bank of Queensland;87

(ff) Citigroup;88

(gg) ME bank;89

(hh) American Express;90

(ii) Bank Australia;91

(jj) Macquarie bank;92

64. Detective Leading Senior Constable Towner noted that between the time of Mr Prendergast’s disappearance and his submission of the coronial brief in 2018, there have not been any verifiable signs of life. In addition, Mr Prendergast has not been linked to any unidentified human remains in the state of Victoria or nationwide. The circumstances in which Mr Prendergast went missing are unknown.

65. At Inquest, Mr Towner stated he believed Mr Prendergast to be deceased and that his death was caused by foul play. When asked whether his death could be the result of homicide, Mr Towner stated: “I don’t believe he disappeared of his own volition, no.”

DNA investigation

66. In 2008 the Belier Task Force was established by Victoria Police to reconcile unidentified human remains by comparing them to missing person reports.

67. In 2011 DNA was obtained from Mrs Prendergast and Lauren Prendergast to compare against specific recently found unidentified human remains, which did not match. On their request this DNA was not placed on the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine (VIFM) database for comparison against all unsolved human remains (UHR) samples held at VIFM. The database matches profiles held within the database both directly and familiarly once uploaded.

68. There is now a nationwide data base to match profiles for missing persons and UHR files nationally. Lauren Prendergast and other members of Mr Prendergast’s family have agreed to provide new samples for the purpose of this database matching by cross-referencing to the national database.

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSION

69. I take into account that Mr Prendergast would now be aged 71 years. At the time he was last seen alive he was in good health, he had a loving wife, a four-year-old daughter, and two stepchildren with whom he was close. By all accounts, he loved and adored his family, and it is inconceivable to them that he would not contact them in any way for 36 years. They believe he is deceased. He had a significant criminal history and there is evidence he was in fear of his life shortly before his disappearance and would carry a pistol with him and sleep with it under his pillow. He was last seen on 23 August 1985 at approximately 2.00 pm leaving his Warrandyte premises in his Volvo, which was later located parked and locked in Heidelberg.

70. I take into account the police investigation undertaken at the time of his disappearance and the extensive proof of life checks undertaken since then. Following the taking of new DNA samples and data base matching, the investigation could be reopened if there is a DNA match.

71. Having investigated the suspected death of Mr Prendergast and having considered all of the available evidence, in all the circumstances, I am satisfied to the coronial standard of proof that Mr Prendergast is now deceased. As his body has never been found I am unable to determine the cause of his death nor the circumstances of his death, however I am of the view the evidence sufficiently supports a finding his death was from foul play, namely a suspected homicide. If any further information becomes available subsequent to this finding, the investigation may be reopened.

72. On the balance of probabilities, I make the following findings pursuant to section 67(1) of the Act:

(a) the identity of the deceased is Laurance Joseph Prendergast, born 5 July 1950;

(b) the cause of his death is unascertained, and

(c) he died on or after 23 August 1985 at an unknown location and, save for being a suspected homicide, the circumstances of his death are unknown.

73. Pursuant to section 49(2) of the Act, I direct the Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages to register the cause of death as ‘1(a) Unascertained’.

74. Pursuant to section 73(1) of the Act, I order that this Finding be published on the internet.

75. It is a terrible burden to never know the fate of a loved one. At the conclusion of evidence at the Inquest, Lauren Prendergast eloquently expressed to the court the enduring pain caused by her father’s disappearance and absence. I convey my sincere sympathy to Lauren Prendergast, Mrs Prendergast and her family.

76. I direct that a copy of this finding be provided to the following: Ursula Prendergast, senior next of kin Jane Prendergast Detective Senior Constable Candice Robson, Victoria Police, Coroner’s Investigator Senior Constable Jeffrey Dart, Police Coronial Support Unit

CAITLIN ENGLISH

DEPUTY STATE CORONER

Date: 17 December 2021

The mysterious disappearance of a Melbourne underworld figure linked to a notorious robbery has been investigated in court.

For more three decades what happened to an underworld figure linked to the notorious Great Bookie Robbery has remained a mystery.

The last time anyone saw underworld figure Laurence “Laurie” Prendergast, he was driving away from his Melbourne home in his silver Volvo sedan on August 23, 1985.

The 35-year-old was never seen again.

His car was found days after he disappeared abandoned and locked on Cartmell Street at Heidelberg, roughly 19 kilometres away from where he was last seen.

But a Victorian coroner declared him as dead after he met with “foul play” in her formal findings.

“It is a terrible burden to never know the fate of a loved one,” Coroner Caitlin English wrote.

Though his body was never found she was satisfied he was dead and labelled it “inconceivable” the loving father never contacted his family since he vanished.

“I am unable to determine the cause of his death nor the circumstances of his death, however I am of the view the evidence sufficiently supports a finding his death was from foul play, namely a suspected homicide,” she said.

He lived in constant fear of being murdered, the coroner wrote.

He slept with a pistol under his pillow and would take it with him when he went out.

But at an earlier inquest in 1990 another coroner said Mr Prendergast had a “strong incentive” to disappear but wasn’t satisfied it was planned or that he was dead.

One of the clues found in his abandoned car was a cigarette butt, and the notorious figure was not a smoker and did not like people smoking in his car, the earlier inquest was told.

The crime figure was a suspect in the Great Bookie Robbery nine years’ earlier, when a group of masked men stole millions of dollars from bookmakers in Queen Street. No one was ever charged.

He was also acquitted of the 1978 shooting murder of Les Kane, one-half of the feared Kane brothers who were major criminal figures in the ‘70s underworld.

A fictionalised version of these events was portrayed in the second season of popular TV series Underbelly.

His sister previously described him as an “infamous criminal” while his wife Ursula said he was a “professional punter”.

The findings came after an inquest in October last year where the underworld figure’s daughter Lauren Prendergast said a formal finding would bring closure to the family.

“I find it very disturbing and hard to fathom any other conclusion could possibly be made,” she said.

“Especially considering every close friend or associate of my father’s has been murdered over the course of the past 40 years.”

She said many other children like herself were left in a “state of perpetual grief”.