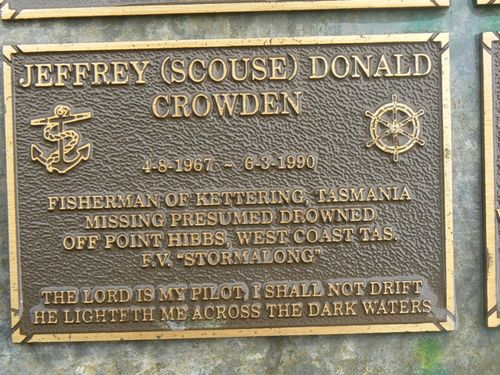

Jeffrey "Scouse" Donald CROWDEN

FINDINGS of Coroner Simon Cooper following the holding of an inquest under the Coroners Act 1995 into the death of: JEFFREY DONALD CROWDEN

Record of Investigation into Death (With Inquest)

Coroners Act 1995

Coroners Rules 2006 Rule 11

I, Simon Cooper, Coroner, having re-investigated the death of Jeffrey Donald Crowden with an inquest held at Hobart in Tasmania, make the following findings. Hearing Dates 3 July 2020 at Hobart in Tasmania. Representation Ms M Figg, Counsel Assisting the Coroner

Introduction

1. Jeffrey Donald Crowden, known to his family as ‘Scouse’, was born in Liverpool, UK, on 4 August 1967, while his father undertook a year-long sabbatical at Liverpool University. He was survived by his parents and three older siblings. He was just 22 years of age when he disappeared off Tasmania’s remote and rugged west coast.

2. Educated locally, Mr Crowden was fit and healthy, an experienced sailor, an excellent swimmer (he had been swimming from a very early age) and an experienced fisherman. He had formal qualifications from the Australian Maritime College including a certificate in Sea Survival as well as Master Class 4.

3. At the time of his death, Mr Crowden was working as a deckhand (or ‘dinghy boy’ as the job is sometimes called) for Mr Christopher Graeme Short, a crayfisherman. Mr Crowden had worked for Mr Short for five or so years before his death. Mr Short had a great deal of confidence in Mr Crowden’s ability. The two men were also friends as well as workmates.

4. Mr Crowden was living with his parents at Saddle Road, Kettering. He was single with no children. He appears to have been a very impressive young man with plenty of ‘common sense’ who was reliable, considerate and quietly confident.

5. Because Mr Crowden died in the course of his employment, an inquest, subject to an exception in the Coroners Act 1995 (the ‘Act’), was mandatory.1

The Role of the Coroner

6. A coroner in Tasmania has jurisdiction to investigate any death which appears to have been unexpected or unnatural. In this case, as has already been mentioned, because Mr Crowden died in the course of his employment, the Act makes an inquest mandatory. An inquest is a public hearing.

7. The definition of ‘death’ in the Act includes ‘suspected death’4. For reasons which will, I hope, become apparent later in this finding, not only do I suspect Mr Crowden is dead, but I am satisfied to the requisite legal standard that he is.

8. When investigating any death at an inquest, a coroner performs a role very different to other judicial officers. The coroner’s role is inquisitorial. She or he is required to thoroughly investigate a death and answer the questions (if possible) that section 28(1) of the Act asks. These questions include: who the deceased was; the circumstances in which he or she died; the cause of the person’s death; and where and when the person died. This process requires the making of various findings, but without apportioning legal or moral blame for the death. A coroner is required to make findings of fact from which others may draw conclusions. A coroner is also able, if she or he thinks fit, to make comments about the death or, in appropriate circumstances, recommendations to prevent similar deaths in the future.

9. The role of the coroner in making recommendations is especially important in the context of workplace deaths.

10. A coroner neither punishes nor awards compensation – that is for other proceedings in other courts, if appropriate. Nor does a coroner charge people with crimes or offences arising out of a death that is the subject of investigation. In fact, a coroner in Tasmania may not even say that he or she thinks someone is guilty of an offence.5 I should make it very clear I do not think anyone committed any crime or offence in relation to Mr Crowden’s death.

11. As was noted above, one matter that the Act requires is finding how the death occurred.6 It is well-settled that this phrase involves the application of the ordinary concepts of legal causation.7 Any coronial inquest necessarily involves a consideration of the particular circumstances surrounding the particular death so as to discharge the obligation imposed by section 28(1)(b) upon the coroner.

12. The standard of proof at an inquest is the civil standard. This means that where findings of fact are made, a coroner needs to be satisfied on the balance of probabilities as to the existence of those facts. However, if an inquest reaches a stage where findings being made may reflect adversely upon an individual, it is well-settled that the standard applicable is that articulated in Briginshaw v Briginshaw, that is, that the task of deciding whether a serious allegation is proved should be approached with great caution.

13. In fact, an inquest was held in relation to Mr Crowden’s death in 1991 at Queenstown by Coroner Barry Waller. Mr Waller made a finding (as he was bound to do) in relation to Mr Crowden’s death. Unfortunately, the finding was attended by significant error, so much so that on 23 March 1992 the late Justice Zeeman of the Supreme Court of Tasmania quashed the finding on the basis there was no evidence (at all) produced to the Coroner to support the finding he made that Mr Crowden was dead. Given the absence of evidence as to Mr Crowden’s death, a fundamental jurisdictional fact to Mr Waller exercising his jurisdiction as coroner, did not exist. Accordingly, Justice Zeeman, as well as quashing the finding, ordered that another inquest be held. Regrettably and inexcusably, the Coronial Court in 1992 failed to comply with that order of the Supreme Court. It has been impossible for me to determine why. Mr Crowden’s parents were never told that any of this had happened. That this was so is a disgrace.

14. This omission only came to light early last year. Since then, a number of steps have been taken by a number of people to attempt to bring the coronial investigation into Mr Crowden’s death to a proper legal conclusion.

Circumstances of Disappearance

15. On 25 February 1990, Mr Crowden set out with Mr Christopher Short on Mr Short’s crayfishing boat, the Stormalong. The two men were the only people on the boat. It was their intention to fish the West Coast of Tasmania, south of Macquarie Harbour.

16. Between 25 February and 5 March 1990, the men fished the coast without particular incident. On 5 March 1990, the Stormalong left the area of High Rocky Point and travelled north along the coast, anchoring approximately a quarter of a nautical mile north east of Bird Island. Late in the afternoon of that day, Mr Short and Mr Crowden set a number of crayfish pots in the area of Bird Island. They did this from an aluminium dinghy. The dinghy, five metres in length and powered by a 30 horsepower Mariner outboard motor, was fitted with buoyancy tanks, flares and paddles. It did not have any life jackets or PFDs on board, and nor was required to by the regulatory regime that was in place at the time. Mr Short operated the dinghy and Mr Crowden set the pots.

17. That evening, the men spent the night on the Stormalong at anchor. They did not consume any alcohol. Mr Short said, and I accept, that the boat was ‘dry’ – that is to say, no alcohol was taken on fishing trips.

18. After an uneventful night, the men got up early, had breakfast and then set out at about 6.40am in the dinghy to collect the crayfish pots that had been set the afternoon before. At the time they set out the evidence is that there was a light westerly wind with a two metre swell. However, Mr Short described the weather as appearing ‘threatening’. Nonetheless, both men were comfortable with the conditions.

19. For what happened next I rely upon the affidavit of Mr Short sworn on 8 March 1990 (and tendered at both inquests). Mr Short said: “We travelled around the south-west corner of the Bird Island, and began to travel west, and were about half a mile from the island, and about a good quarter of a mile from the main shore, when the dinghy was unexpectantly [sic] swamped. At that time we were about 300 metres outside the line of the breaking waves. At that stage we were not concerned. “Within about 1 – 2 minutes the dinghy lost stability and overturned. “The dinghy is fitted with buoyancy tanks, flares and paddles and as a result we both made arrangements to stay with the dinghy. We removed our gumboots, and were attempting to retrieve floating gear from around the dinghy, when I was washed away from the dinghy, by another wave. In the meantime the weather was deteriorating rapidly, in that a rain squall accompanied by a strong south west change had overtaken us. “At the time the boat overturned, [Mr] Crowden was dressed in white gumboots, blue jeans, a set of wet weather pants, a shirt, a wool jumper, and possibly a blue windcheater, along with a yellow wet weather coat. He was not wearing a lifejacket, nor was a lifejacket in the dinghy. I was similarly dressed, and also not wearing a lifejacket. “As soon as I was separated from the dinghy, I began to remove other clothing and instructed [Mr] Crowden to stay with the dinghy. By the time that I freed myself of unwanted clothing, the dinghy was some distance away. [Mr] Crowden was at that stage still on the upturned dinghy. “I believe my chances of returning to the dinghy were poor, I decided to swim for a gap between Bird Island and the main shore some quarter of a mile from my current position. “After I had been swimming for approximately 15 minutes I caught a glimpse of [Mr] Crowden still with the upturned dinghy. This was the last time that I saw him.”

20. Mr Short eventually made his way back to the Stormalong. He was unable to say how long that took him; and I am unable to make any finding in that regard, other than to say that it took him a considerable period of time. Once on board his boat, he weighed anchor and made his way around the other side of the anchorage expecting to find Mr Crowden and the dinghy, but saw neither.

21. He raised the alarm using the emergency channel on his marine radio. Another fishing vessel, the Warrain skippered by Mr Geoff Noye, was close by and quickly responded to Mr Short’s request for assistance. Other evidence indicates that Tasmania Police Search and Rescue personnel in Hobart were notified at 8.50am on that day of the emergency. The rescue helicopter was dispatched and an aerial search of the area commenced.

22. A land and sea search was undertaken by police, divers and volunteers, including local fishermen over the next several days. No trace of Mr Crowden was found as a result of that search although late on the day of 6 March, members of Tasmania Police in the rescue helicopter located the aluminium dinghy. It was found overturned on some rocks in a bay on the shoreline on the inside of Bird Island. The dinghy was recovered by fishermen and found to have sustained some structural damage. In addition to the dinghy, a paddle and red fuel tank, identified as belonging to the dinghy, were located on the seaward side of Bird Island. These were also recovered by fishermen.

23. On 8 March, a bottom viewer and the engine cowl from the outboard on the aluminium dinghy were located by police officers.

24. On 13 March, the skipper of another fishing vessel, Mr Glenn Whayman, found a pair of orange waterproof trousers and a yellow waterproof jacket on the north-west side of Bird Island. Mr Short later identified the jacket as the one Mr Crowden had been wearing when he last saw him with the overturned dinghy. The waterproof pants were identified as having been in the dinghy when it overturned.

25. The evidence is that on 16 March 1990 police continued searching utilising the police vessel Freycinet.

26. More searching took place in July and September 1990, both on land and at sea. No trace of Mr Crowden was found as a result of any of those searches.

27. Senior Sergeant Adam Spencer of Tasmania Police gave evidence at the inquest. He is a senior police officer with a good deal of experience in relation to search and rescue activities. He said that as part of his investigation of Mr Crowden’s death, he had reviewed the searches that had been conducted for him. Senior Sergeant Spencer said, and I accept, that the search carried out by the authorities in March 1990 and subsequently were of a high standard.

Subsequent Investigations

28. In 2009 a number of enquiries were undertaken by the Tasmania Police Missing Persons Unit. Those enquiries were, I am satisfied, extensive. They involved interrogating databases held by numerous state, federal and private agencies. If Mr Crowden was still alive I am satisfied that those enquiries would have identified that fact. No evidence, at all, was found of Mr Crowden being alive since 1990.

29. Mrs Stella Crowden, Mr Crowden’s mother, swore an affidavit in October 2019 confirming she has had no contact at all with her son since 1990.

Conclusion

30. This additional evidence, coupled with Mr Short’s eyewitness account of what occurred on the morning of 6 March 1990 in the waters near Bird Island on Tasmania’s west coast, satisfy me, to the requisite legal standard, that Mr Jeffrey Donald Crowden is dead.

31. I consider it is certainly possible that if Mr Crowden had been wearing a PFD on 6 March 1990 he may have survived, although there is no way of being certain about this. I note also the evidence of Senior Sergeant Spencer and Mr Short as to changes in respect of the availability of safety equipment and the regulatory regime relating to its use since 1990. I am of course also well aware of those changes both as a member of our community and as a coroner.

32. Those changes – the requirement to wear a PFD and the availability of personal locating beacons amongst others - satisfy me that no real purpose would be served in making any recommendations as a consequence of these findings.

33. I wish to thank Ms Madeleine Figg, Counsel Assisting, Senior Sergeant Adam Spencer, and Constable Jennie Richardson for their assistance in bringing this sad matter to a long overdue legal conclusion.

34. I offer my sincere and respectful condolences to Dr and Mrs Crowden and their family on the loss of a much loved son and brother.

Dated 17 July 2020

at Hobart in Tasmania

Simon Cooper

Coroner

A young fisherman who disappeared in seas off Tasmania's rugged west coast 30 years ago has been formally declared dead by a coroner who labelled a decades-long delay in the investigation "a disgrace".

Deckhand Jeffrey 'Scouse' Crowden, 22, set off with friend and boss Christopher Short to go crayfishing near Macquarie Harbour in late February 1990.

While retrieving cray pots on the morning of March 6, their five-metre dinghy was overturned after being unexpectedly swamped by waves.

Mr Crowden stayed clinging to the tinny while Mr Short swam back to their main boat before radioing for help.

It was the last time Mr Crowden was seen alive, with a large-scale search in the days following finding the damaged dinghy on rocks.

In findings published on Friday, Coroner Simon Cooper said Mr Crowden may have survived if he was wearing a life jacket.

The dinghy didn't have personal flotation devices, which weren't legally required at the time.

An inquest into Mr Crowden's disappearance was held in 1991 but its findings were quashed by a Supreme Court judge the following year due to "significant error".

The judge ordered a second inquest be held, but the coroner's court didn't follow through, with the oversight not coming to light until early last year.

Mr Cooper wrote it was regrettable and inexcusable that the order wasn't followed.

"It has been impossible for me to determine why Mr Crowden's parents were never told that any of this had happened," he wrote.

"That this was so is a disgrace."

Mr Crowden, who was born in the UK, was a fit and healthy experienced sailor and excellent swimmer.

He had worked with Mr Short for five years before the accident.

In evidence provided to the inquest, Mr Short said he had been swimming for 15 minutes when he last caught a glimpse of his mate.

Six days after going missing, Mr Crowden's yellow jacket was discovered at nearby Bird Island.

Mr Cooper said he was satisfied to the requisite legal standard that Mr Crowden was dead.

He noted laws around life jackets had changed since 1990.

A young fisherman will finally be declared dead some 30 years after he was lost at sea, as more chilling details are heard about the last time a cray fisherman saw his deckhand.

THE year was 1990 when fisherman Christopher Short woke on the rocks of the rugged West Coast after blacking out and being washed ashore.

He couldn’t feel his right leg, but worse, he couldn’t see his young deckhand – Jeffrey Donald Crowden – who had waited with their dinghy after conditions had suddenly turned extreme.

Mr Short, then 36, didn’t waste any time. He crawled to where their main vessel Storm Along was anchored, using his hands to pull himself out of the water.

He started Storm Along’s engine and began pulling the anchor, issuing a Mayday alert and calling on help from another fishing boat about half a mile away.

Mr Short joined police and search and rescue teams to find the 22-year-old, combing the area near Point Hibbs for three days and two nights.

The dinghy was found as Mr Short was returning to Strahan, ordered by police to stop searching.

Mr Crowden was never seen again.

On Friday, 30 years after he was lost at sea, an inquest into Mr Crowden’s disappearance and presumed death was held at the Hobart Coroners Court.

He will soon be officially recorded as deceased, following an administrative oversight that has led to decades of delay.

An inquest was first held into the matter in 1991, but the findings were overturned shortly afterwards by the Supreme Court of Tasmania for legal reasons.

Mr Crowden’s parents, who are now in their 80s, were present in court on Friday, with Coroner Simon Cooper apologising for the oversight.

Mr Short gave evidence by video link, tearfully telling the Crowdens that “you never forget”.

“I just want to offer my condolences to both of them,” he said.

Mr Short said Mr Crowden had worked for him for about five years and were “together most of the year”, describing him as a “very competent deckhand” who loved fishing and being aboard the boat.

The pair had been retrieving cray pots on the day in question near Low Rocky Point when a wave broke around the dinghy, half-filling the vessel, before another wave overturned it.

Neither were wearing life jackets, which Mr Short said weren’t compulsory at the time and made too bulky for cray pot fishing.

“Jeff just said ‘I’ll stay here with the dinghy’ and I said ‘I’ll swim and bring the boat and pick you up’,” Mr Short said.

“That’s the last time I saw Jeff.”

A Mercury article from 1990 quotes Mr Short as saying he’d wrenched his back from the episode, but “the real pain’s in my heart”.

“By all rights I should have been the one that didn’t make it, not Jeffery,” he said.

Mr Cooper will deliver his findings in the coming weeks.