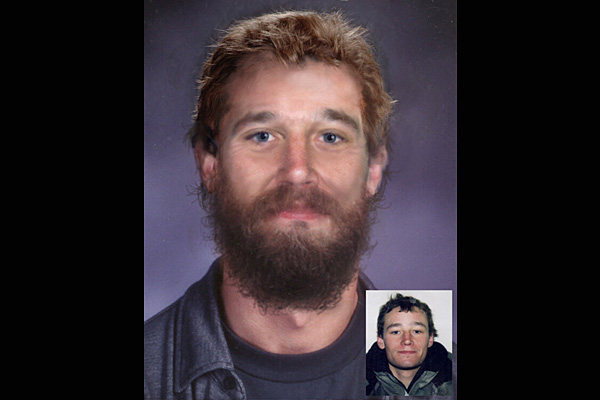

Above - age enhanced photo of what Ian may look like today

Year of

Birth: 1980

Hair: Brown

Eyes: Blue/green

Weight: 85kg

Height: 185cms

Significant identifying feature:

Tattoo - Cartoon style round bomb with lit fuse located between the

forefinger and thumb of left hand measuring 2cm x 2cm

Circumstances:

***************************************************************************

Ian Stanton went missing from Bundanoon in the NSW Southern

Highlands, just after his 23rd birthday. The last person to see him was his dad

Norm, on Friday, May 9, 2003. Since then, Norm and his wife Jean have feared the

worst — just knowing Ian's okay would bring them enormous relief. Norm tells his

story ...

- with thanks to WOMAN'S DAY magazine

"He had a good 23rd birthday, spent at home. Ian was in good spirits, saying it

was his best birthday ever.

A week later I took some mail and food to his flat and we had a brief chat. He

wasn't quite with it. He was probably smoking dope at the time.

Our son started smoking marijuana at a young age and he graduated to heroin in

his mid-teens, which he kicked when he was 19. I've no doubt marijuana triggered

a schizophrenic condition — I don't know whether there's a gene or whatever, but

it has definitely presented problems for our young man.

On the following Tuesday, my wife Jean went to see him and he wasn't there. On

the sink were the groceries and mail we'd left earlier — it wasn't even touched.

His credit card, wallet and keys were still there. He was a bit short of money,

yet there was a $10 note and quite a lot of change lying around. All his clothes

were there and everything was left with the door unlocked. He'd just gone.

It led me to fear the worst. He probably decided to pull the pin. Since then

we've experienced the rollercoaster of emotions. You hope, but the police

haven't been able to shed any light.

He was very much a loner; we were probably his best friends. Ian had been

involved with WIRES — he loved animals and rescuing wildlife, and he had a brief

stint on a local FM station. He was in and out of different jobs, and there were

times he had his life on track. But unfortunately he'd slipped away a bit in

those weeks prior to him leaving.

He was living a kilometre from Morton National Park and looking for him in there

is like looking for a needle in haystack. Ian did a lot of bushwalking and he

knew the area well. The ranger told us Ian would know where to go where no-one

would find him.

It's the not knowing that's the killer for us. It's a tough time, but you try to

be positive."

If you have any information, call the NSW Police Missing Persons Unit on 1800

025 091.

Posted - ABC

Posters of a missing man will be distributed in the New South Wales Southern Highlands after concerns were raised by the man's father.

Ian Stanton was last seen seven years ago.

He was living in an apartment above a newsagency in Bundanoon. His father, Norm Stanton, says his son had drug and mental health issues but was in good spirits just before his disappearance.

Earlier this month, Mr Stanton spoke to the national media regarding an Australian Federal Police campaign to circulate age-enhanced images of his son.

But he is concerned that none of the posters had been circulated locally.

Police from the Goulburn local area command have confirmed that they have received posters of Ian Stanton and will circulate them in the Southern Highlands this week.

His father is hoping the images will lead to further information.

This story first appeared in the Mercury on June 2, 2013.

Three years after his son went missing, Norm Stanton found himself walking the paths of a Buddhist monastery poised on the edge of the Morton National Park.

As he walked and meditated on his loss, he heard the words repeated like a mantra inside his head:

"I'm still with you, Dad."

This was the moment when he could walk no more, when he found a log, when he collapsed and sobbing engulfed his body.

"I felt there was an element of truth," Stanton, a retired primary school principal, said.

"His presence was with me even if he is missing, Ian's memory is still with me in my head and heart, and I thought, 'Let's inscribe it on my body and get a tattoo'."

So it was that, a few weeks ago on his son's 33rd birthday, Stanton found himself sitting in a tattoo parlour for his first piece.

Rolling up his sleeve, this gentle, thoughtful, sad and compassionate man reveals the blue-black ink still fresh on his skin:

"I am still with you Dad." The Grebe.

Ian Stanton was a challenging son, who carried the family nickname of a bird whose portrait appeared on a stamp when he was a baby - a bird with a small tuft of hair like his own.

He was adored and happy as a child, but started smoking marijuana as a young teenager and later became so difficult that he left home for a refuge before he was 17 years old.

Probably an undiagnosed schizophrenic, he led a chaotic life. He grew dope and may well have sold drugs for a while.

Sometimes he worked, sometimes he did not. Sometimes he had a girlfriend, but none lasted. He developed a heroin habit for a while, but kicked it.

He was a WIRES volunteer, was artistic, became an amateur actor and community radio announcer.

He was a talented cartoonist and - at his best - gentle, funny and clever.

The last time the family were together was a happy occasion, his 23rd birthday, but a week later he was short and dismissive when his father turned up at his home in Bundanoon to deliver some mail.

A week later, he was gone - no-one knows the precise date of his disappearance - and, like 12,400 people every year in NSW, he was reported missing.

His sister, Alex Speed, later described the experience as "living with a permanent bruise under our skins".

The first and most important fact to realise about missing people, according to Chief Inspector Paul Roussos, manager of the Missing Persons' Unit in Sydney, is that the vast majority turn up again.

Of the 12,400 reported missing, only about 30 people remain missing after a year - though some are found dead through accident, suicide or misadventure.

"If you have a concern for someone's welfare, then that starts to become a missing person matter," Roussos said.

"That's why we say, if you have a concern for a person then report it, don't wait.

"It's important not to wait because if there is foul play, or if something's gone wrong, it's important to have the authorities on the matter as quick as we can."

If police treat reports of missing people differently now, it may be partly due to the efforts of Stanton, who tells his family's story to all new recruits passing through the NSW Police Academy at Goulburn.

It would be fair to say, however, that the Stantons' experience was not a good one.

"I say to cadets 'Don't treat people like I was treated. Don't make assumptions that that person is going to turn up'," Stanton said.

"When I reported Ian missing at a police station, the officer didn't take any details and just fobbed me off. It was a really lazy approach."

Worse still, there were only cursory search attempts at the most likely location for Ian, the Morton National Park, where he used to go for long rambles through the bush.

So Stanton, his wife Jean, and other family members found themselves bashing through the undergrowth in a desperate attempt to find Ian.

"Those early days were heart-breaking stuff, not knowing what had happened, not knowing what to do," Stanton said.

"We did our own searches but we're not bushwalkers and we're not trained to do it."

They eventually stopped when they realised they were lost in the bush, and saw the irony of the parents of a missing son going missing themselves.

It was up to Stanton to ring police stations, refuges, hospitals and mental health institutions in a vain attempt that any had seen his son.

Even now, Stanton hands out photos of Ian when he talks to service clubs, because, as he says: "You never know".

You never know.

Stanton calls it the Clayton's Loss - after the non-alcoholic drink advertisement, whose line was "The drink you have, when you're not having a drink".

"For me, this is the loss you have when you don't really know if it's a loss," Stanton said.

And that is the point.

That, according to Liz Davies, the co-ordinator of the Family and Friends of Missing Persons, is what makes the fact of a missing person so hard.

The group is the only one of its type in Australia, and was founded in 2000 after lobbying by families of missing people and is funded by the state government.

Quoting an American expert, she calls it "ambiguous loss" for that state when a loved one is both psychologically present but physically absent.

"The struggle for families is finding a way to sit with not knowing," Davies said.

"They have to find a way of living with the ambiguity of the missing person.

"The recipe is a very challenging one.

"We talk with families about finding a place of comfort with themselves, of sitting with the not knowing and lack of clarity, of being able to move forward with their lives.

"If you come at missing from a problem-solving, solution-focused perspective, it confounds you.

"There may be no solution, though we would love for it to be possible.

"The solution is that the person returns, so families work to find a way of waiting that is tolerable, to find a way of living with not knowing."

The group provides a range of support, including helping support groups such as the one that attracts up to a dozen people to share experiences every couple of months in Corrimal.

"I don't believe we have the right to ever say to a family that there is no hope," Davies said.

"I don't believe families ever give up hope, though the nature of their hope might change."

Yet hope is no simple proposition.

Bob and Sue Neville have travelled around Australia, looking for their son, Bobby.

No-one knows this better than Bob and Sue Neville, whose son left the family home in Coledale with the words: "I'm just going for a walk, Mum".

That was one warm September day in 2008, leaving behind him parents tormented by questions that may very well never find an answer.

It was not unusual for Bobby to leave, though he would always be in touch eventually, but this time, Sue felt a mother's intuition when walking the next day with Bob.

"I just had this overwhelming feeling that he's not coming back and that something had happened. I almost dropped to my knees," she said.

Is he alive? Is he dead? Would he leave without explanation? Does he want to be found? Did he kill himself?

Bobby Neville’s boat is still in their yard, last used a couple of weeks before he left.

His old bomb of a car waits for the return of its owner. The fence and the sandstone terrace he built on the property are reminders of his presence.

‘‘He is so embodied in our property that we stay, even though our property is getting very difficult for us to manage now,’’ Sue, a retired teacher from Figtree High, said.

Like the Stantons, the Nevilles are torn apart by the love for their child and have only lately learned that they sometimes need to put him to one side if they are to retain their sanity.

Bob is a retired draftsman and courier, a bearded bush character who is a straight-talker and a man proud to set his own course, but in constant physical pain from an old work injury.

The mental pain, too, is becoming hard to mask or to endure.

Bob admits that the void is ‘‘tormenting to the extreme’’ and that he’s finally made an appointment with a counsellor to get help.

He reveals that he is on medication to settle him down for the interview because, that morning, he was ‘‘shaking like a dog shitting razor blades’’.

‘‘Sometimes, I talk to him while I am doing things, it’s just a thing we do, like going to the grave and putting flowers there,’’ Bob said.

‘‘I had got to the stage where I’d tell him I’d have to go away for a week or two – ‘You look after yourself and I have something I have to do’.

‘‘I have found the spectre of it is too great at times.’’

This is the dark side of parental love, revealed by the constant and desperate searching of two parents who would give anything to hold their son in their embrace once more.

The Nevilles have travelled all over Australia in search of Bobby.

They’ve been to Adelaide, travelled the Ghan to Alice Springs, driven up to Queensland and the NSW North Coast.

They would turn up to police stations, caravan parks, taxi ranks – anywhere – always armed with flyers showing photos of Bobby.

Every time their hopes are raised with a possible sighting, or the discovery of bones in an outback grave, they are smashed once more.

One time, they had only just returned from a trip up the North Coast when they received a phone call from a caravan park owner who reckoned she had seen him.

It sounded hopeful – a man with a skateboard under his arm, talking about fishing and wondering if he could have a shower and a coffee.

So Sue turned right around again, seeking leave from her job, and travelled for five hours to Laurieton.

When she arrived, she showed the owner more photos of Bobby and suddenly the certainty faded. Maybe it wasn’t him after all.

But hope would not stop tormenting the parents, so they returned six months later and traipsed seven kilometres up the beach, searching the scrub where homeless young men were living rough.

The adrenaline of hope pushed Bob on until he remembered his pain and knew he could not return, hoping only that there would be help further on.

‘‘You do lose your equilibrium and that’s where I am at the moment,’’ Bob said.

‘‘It’s not good is it? I have lost my equilibrium, I bloody have.’’

Because another strange torture of missing is that – in many ways and in contrast to other forms of grief – it becomes harder to bear over time.

Another member of the Corrimal support group is Karen James whose father, former serviceman and taxi driver Leslie Hicks, vanished shortly after breakfast on Easter Sunday, 2008.

He left his Woonona retirement village on a short walk to his daughter’s house and has never been seen since.

For three years, James was convinced her father was alive, despite that fact that he was nearly blind and needed daily medication for his diabetes.

She believed he may have forgotten she was away at her caravan down the coast that day, and instead attempted the journey to his son’s house on the mid-North Coast.

It took three years for her to buy a burial plot at Kembla Grange – her hand was forced because they were selling fast and she wanted him buried near her mother, who died in 1989.

‘‘That was when I started to accept that I had probably lost him,’’ James said.

‘‘I wanted some place to go, but I have nothing to write on the headstone because I have no date of death.’’

James only found out about her father’s disappearance on the Easter Monday, and still regrets those 17 lost hours when he was gone but not yet reported missing.

Like the Nevilles, she has had hopes raised and then dashed.

‘‘If I am driving, I am still looking the whole time,’’ she said.

‘‘If I see an old man the right height, if I can’t see him properly, I have to do laps until I can get a good look. I am always on the lookout.’’

She’s been to see three clairvoyants, but has never had a message from the other side.

One saw his body in thick lantana and brambles in bush between the Bulli Pass and Pope’s Road, where he used to live.

But when police searched the area, they found nothing.

Until the past few months, James was reluctant to leave the house in case she missed a phone call from her father and medication to combat anxiety has increased in strength as time passes.

‘‘It’s funny, because when you lose somebody from death, it gets easier every day,’’ she said.

‘‘Because you have put them to rest, and you know they’re gone.

‘‘With this, as time goes on it gets harder. You think about all the what-ifs.

‘‘The hope starts to fade and you wonder if there might have been foul play.’’

She hates the rain or when it’s really cold because the part that thinks he’s still alive worries that he is cold. The part that thinks he is dead doesn’t want his body laying out there.

‘‘I feel despair,’’ she said.

One of the men in the Corrimal group recently heard that his wife’s remains had been found and the other people congratulated him.

The wait was over, even if the questions were not.

But although James would welcome the news that her father’s body had been found, she knows that would not be the end.

‘‘Everybody says that you’ll have closure, but that’s a word I hate,’’ she said.

‘‘You won’t have closure because you don’t know what happened.

‘‘You don’t know how they died or what they went through.’’

The only truly happy ending for any of these families would be if their loved one walked in through the door.

And even then, the questions may never have answers that satisfy.

JENNY BROCKIE: Norm Stanton, your son Ian went missing ten years ago, I mean do you relate to any of this?

NORM STANTON: Certainly do Jenny. The privacy issue was an enormous source of frustration for us, particularly in the early days when the police investigation was so tardy. Just a couple of examples if we'd been able to find out Ian has accessed his bank account it might have given us some indication of where he was, but we weren't able to get any information about his banking account at all. CentreLink were not just uninformative, they were quite rude and obstructive.

But probably the worst example is that we, Ian had been seeing a counsellor and we tried to get some details of those sessions to find out what his state of mind was at that time so we could better understand why he'd gone missing and we were unable to get any details at all of those sessions. But what is disturbing is that when the Coronial process came up four years later, we were given a police brief which contained two pages of a statement from the counsellor divulging all those details that might have helped us a little bit understand what was going on in the early stages. Suddenly now it's not a privacy issue and it comes up in the brief. So we found that quite disturbing.

JENNY BROCKIE: It's been ten years now?

NORM STANTON: Yes.

JENNY BROCKIE: Do you still have hope? What do you feel you know at the end of that ten years?

JEAN STANTON: Actually ten years for me particularly is easier now because I accept that he's dead. So, and dead's being saved so that's fine. The early years are the hard ones and it's hard talking about it because it's something you keep close to your heart I think. But, and it's hard seeing him up there so that's hard. But no, I think we have a lovely family, we have four other children and grandchildren and we get on with our life. And you must make the most of each day because they're precious days.

JENNY BROCKIE: And Norm, do you have a similar view to your wife? Do you still have any hope at all?

NORM STANTON: Probably not Jenny and that's one of the issues around, for families I think around missing persons. The fact that everyone responds very differently, I think, and there's no right or wrong way of doing it. Sue Neville would no more get a tattoo on her forearm as I have, than what I would go knitting Sue's quilt.

SUE NEVILLE: It's not knitting, sewing.

NORM STANTON: Sewing a quilt, there you are. So I think it has the potential, this kind of situation, for families to be really harmful to relationships certainly but Jean and I are tight and we've survived.

By Larissa Waterson|

Ian Stanton was a 23-year-old resident of Bundanoon in the NSW southern highlands.

He was one of five children to parents Norm and Jean Stanton and lived just 30 minutes from his folks in a flat near the town centre.

His creativity and artistic flair accompanied a strong passion for music, while a restless disposition and innate curiosity saw him dabble in, yet never master, a number of different trades and industries. He had a one-time gig working for a radio show and spontaneously took up a jewellery-making course.

Unlike his ever-changing hobbies and job stints, one thing remained constant in Ian’s life - the love of his parents.

“He was a good guy, he got on well with people. Obviously I'm biased -- I'm his Dad,” Norm Stanton tells 9Honey.

“He was even-tempered and if he put his mind to something he could achieve great things. He was wonderfully creative.”

Around May, 2003, Norm fondly recalls the family’s celebration of Ian’s 23rd birthday.

“He said it was the best birthday he’s ever had,” Norm says.

The next week, Ian disappeared.

“We went round to his flat with some fresh groceries and some mail for him and that was the last day we saw him.

“We visited him a few days later and found the door ajar, his wallet and keys left behind. It seemed as if he'd simply walked out.

“And that was the start of the journey that we've been on for the past 15 years.”

Realising your son has disappeared

At first, police didn’t take Ian’s disappearance seriously.

When a panicking Norm and Jean realised their son probably hadn’t “ducked down to the shops” or “gone for a walk”, they reported the issue to a sluggish policeman at the local command.

“He didn’t regard it with any urgency and so when we got home I phoned the police helpline and they said it should have been acted on immediately … but it wasn’t.”

Several days passed and, while the family conducted their own searches and distributed flyers, contacted ex-girlfriends and started arranging trips to Canberra and Sydney -- areas Ian had frequented, the police had still not investigated Ian’s flat.

“There was no sense of urgency that you'd expect in these circumstances -- they were very laid back, in fact, they didn't even look in his flat for several days which one would have thought would be one of the first things to do.

“We could have acted a bit quicker on this,”-- Ian recalls the exact words one of the superintendents said to him weeks after Ian’s disappearance -- when media attention and community concern had increased.

‘What if?’-- The hardest part

After years of searching and investigating -- scouring the nearby national park Ian used to take bushwalks in, searching homeless shelters and refuges everywhere, distributing posters, calling, travelling and questioning -- a 2007 coronial inquest declared Ian deceased.

But Norm says there have been countless examples of missing persons deemed dead who one day show up -- a hope that, no matter how much time passes, makes dealing with the disappearance of a loved one so difficult.

“I have to say that, in reality it doesn't really get any easier despite the passage of time,” he says.

Thirteen years after his son went missing, Norm said one of the most difficult things to do is walk down the street without frantically searching for Ian’s face in the crowd.

"One of the hardest things is seeing people on the street when you're out and about.

“You see someone who resembles Ian -- it might be his gait or his appearance or whatever -- your heart skips a beat, it really does, and you think 'Is that him?!' so you try and get a better look, and it’s not.”

“It’s ever present, it’s always with you,” he says.

Moving house

Two years ago, when Norm and his wife made the tough decision to pack up and move house, they didn’t realise just how crippling the emotional impact would be.

“I’ve always been conscious that if Ian was still alive he might just return to our family home. However that assurance is no longer there when you move,” he says.

“One of the most gut-wrenching aspects was clearing out his belongings.

“When Ian went missing we had bundled things up and stored them under the house. They were out of sight but we had plenty of reminders of our son inside: a childhood painting of his Dad, a gnome he gave us as a joke for a birthday, photographs of course, a wonderful painting of a kookaburra, even a money box he’d made in high school.

“Some of the things we just couldn’t part with. My wife couldn’t let his Mambo shirt, so typically Ian, go to the op shop. I held onto a rugby trophy and the cards from his 23rd birthday.”

“And of course all the old feelings from the roller coaster days following his disappearance were revived: especially the guilt, the regrets, the conjecture.

Moving on

Even though Ian has been formally declared deceased, Norm still clings to the hope of one day seeing his son again.

“We've probably entered a phase now of somewhat acceptance, especially since the coronial inquest. But we've heard of stories of other people who have come back many years later and so you do cling to that hope as desperate as it may be.”

AUGUST 5 2020

Gone without a trace and their families left with a constant

feeling of the unknown.

For many, Missing Persons Week is an opportunity to raise awareness, for others it's a cruel reminder.

Missing Persons Week is an annual event that takes place during the first week of August to raise awareness of the significant issues surrounding missing persons.

The week is also used to profile long-term missing

persons, and to educate the Australian community.

For 17 years a constant void has been in Norm Stanton and

his family's lives.

From May 9, 2003, his son Ian Stanton left his Bundanoon

flat and never returned.

Norm recounts that Ian had just celebrated a birthday and was in high spirits, then he disappeared.

"It was just a week after his 23rd birthday," Mr Stanton

said.

"He had spent it with his parents and sister Ella. He'd

described it as "his best ever".

"He then just walked out, leaving behind his wallet,

keys, money and clothes."

Ian grew up in a positive and loving home. When he began his teenage years that is when problems began to arise, Mr Stanton said.

"Ian had a wonderful childhood, much adored by his four

siblings, his parents and grandparents," Mr Stanton said.

"However, about 13, when he discovered marijuana, his

personality and behaviour changed. That culminated in him leaving home

at 16.

"We became aware Ian had mental health issues and he

continued to have his ups and downs into adulthood.

"He was always a sensitive, quite introverted person, with a strong social conscience and a good sense of humour, but struggled to maintain stability in his life."

When Ian failed to contact his parents for several days

in May 2003, they became worried.

"On the Friday before Ian's disappearance I'd gone to his

flat in Bundanoon to take some clothes he'd left at our place, some mail

and some food," Mr Stanton said.

"He'd been in the shower, looked a bit "spaced out" and

certainly didn't want to invite me in. So he thanked me and we said

goodbye.

"We didn't hear from him over the weekend, so on the Tuesday my wife Jean went to his place and found the door open.

"She didn't go in, thinking he'd popped out to the shops.

We both went back on the Thursday because we were a bit uneasy about him

not being in contact.

"This time we went inside and found the food in the kitchen untouched, keys, money and wallet on the table; it just looked and felt as if he had simply walked out and not returned."

The effect for the Stanton family was immediate and

surreal.

"The impact was immediate after reporting Ian as missing

to the police at Bowral and it was very unsettling," Mr Stanton said.

"I never contemplated him going missing. It just wasn't

in my consciousness. There was such a surreal air to it all; this can't

be happening to us.

"It was all very overwhelming. There was constant liaison

with police, the Missing Persons Unit and various agencies.

"I began to encounter the frustrations of privacy

regulations. We searched in Morton National Park as best we could and

put up posters.

"I visited refuges and contacted hospitals and mental

health institutions and also some of Ian's past friends. I engaged the

Salvation Army Family Tracing Service and joined the NSW Missing persons

committee.

"It was frustrating not achieving any success."

The Stanton family have experienced every possible emotion. Reaching out

for help wherever they could find it, the Stanton family have never given up, but also need to ensure their own well-being.

"In the early days you are on a roller coaster, going in

and out of the stages of grief," Mr Stanton said.

"At some stage that analogy transitions to a suspension

bridge.

"At one end is the rational belief that I have to move on

with life, let go of the past and make sure I am well and caring for the

other loved ones in my life.

"At the other end is this strong emotional attachment

that I just can't leave. A need to hang onto the memories of my son.

"I would say that over time we have reached a stage of

acceptance, but he is always in our thoughts.

"Soon after Ian went missing, the police advised he had

been seen by two girls working in Bundanoon, but nothing ever came of

it.

"On one occasion we had a report that he'd been beside

the Federal Highway, but it wasn't followed up.

"In the early days Jean contacted clairvoyants who revealed various scenarios, but nothing concrete ever eventuated."

With normality eluding the family, they had to overcome and adapt a new 'normality'. But, no matter how life seems to roll on, there will always be reminders of Ian.

"After such a long time it's evolved to become a new

normality," Mr Stanton said.

"There are still however so many unsettling experiences

to be encountered, even years after the event, when a member of your

family goes missing.

"Some are anticipated triggers, like birthdays,

false sightings, anniversaries and announcements about

missing persons in the media.

"Some sneak up on you. I found moving house a few years

ago was one of those.

"Certainly there is no closure. The experts describe it

as ambiguous loss.

"I refer to the situation as the Clayton's loss: the loss you are experiencing when you're not sure if it really is a loss. Part of you wants to get over the grief; the other part thinks that just maybe, we try to focus on our fond memories as part of our acceptance."

There is no advice you can give to heal a wound of the unknown. But, the Stanton family know how to survive and look after one another.

It's difficult to provide generic advice on this issue

because everyone reacts so differently to the situation, even within the

close family," Mr Stanton said.

"However, I recommend you keep the lines of communication open with police, ensuring they are doing their best to find the person.

It's advisable to seek help through the Family and

Friends of Missing Persons who provide very good counselling in

negotiating the different phases of grief and can offer useful practical

advice, especially at times such as the coronial inquest.

"Above all, take good care of yourself."