Two decades on and there are more questions than answers about Stacy de Sielvie’s disappearance.

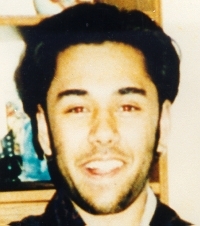

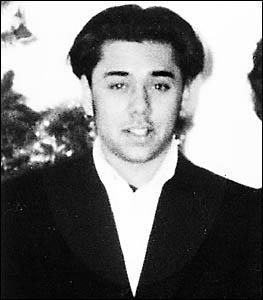

Date of Birth: 1972

Eyes: Grey

Hair: Brown

Height: 160cm

Build: Thin

Complexion: Olive

Circumstances: Stacy De Sielvie left his home in 1992 to work his way

around Australia. Until April 1994 he was in regular contact with his family.

His family last heard from him by phone on 20/4/94 when he called from Armidale

NSW. He said that he was making his way back to Sydney, but he never returned to

his residence and has not been seen or heard of since.

In April 1994 he rang them asking for help with money. His family deposited funds into his account which he withdrew from the bank.

At the time Stacy was living with a family in Darlinghurst but he never returned to the house.

Stacy’s parents are eager to speak with him but would abide by his wishes if he doesn’t want contact with them. They only want to know that he is safe.

Stacy is Sri Lankan and 160cm tall with a thin build, black hair and grey eyes. He has a small scar on his right hand.

The parents of a missing Victorian man, last known to be living and working in Lismore in 1994, are pleading for information after 12 years of searching with no answers

A mother’s worst nightmare

Two decades on and there are more questions than answers about Stacy de Sielvie’s disappearance.

The boy with the grey eyes

Each year, more than 38,000 people are reported missing in Australia. Although 95 per cent are found within a week, about 2,000 people remain missing long-term. Stacy de Sielvie is one of them. His story is part of an SBS series on missing persons from multicultural backgrounds.

Nalini de Sielvie had just turned 20 when she gave birth to her elder son, Stacy. Every August, on his birthday, she lights a candle for him. "I always know his age because he's exactly 20 years younger than me," she says. "He'd be 44 now."

Her first-born had grey eyes and a madcap sense of humour. Like his younger brother, Christian, he was a gifted child, especially good at music and writing and drawing. In his teens, he became a troubled soul. At 20, he left the family home in Melbourne. At 22, in 1994, he went missing.

Nalini sighs as she rifles through a bulging cardboard file of police statements, newspaper articles, Missing Person posters, correspondence with the Salvation Army's Family Tracing Service – and a two-line coroner's report, recording an open finding on Stacy.

"You never think when you have children that you're going to face this," she says, gazing out of her living-room window at Port Phillip Bay, on Victoria's Mornington Peninsula.

"Every morning you get up and you think, this can't be. Somehow you find the strength to keep going. I keep myself busy so I don't sit and dwell. But sometimes you break down and cry and cry."

Despite the passage of two decades, and a fresh investigation in 2006 by a dogged NSW detective, many questions remain unanswered. Among them: why did Stacy marry a young Frenchwoman in Sydney, only for her to leave the country four days later? Why did he move to Lismore, in the northern NSW hinterland, without telling his parents?

Stacy's family last heard from him on 20 April, 1994, when he called his father and said he was stranded in Armidale, in NSW's New England region. His girlfriend had driven off following a row, he told him; Stacy's wallet and all his belongings were in the car.

A week earlier, he had phoned Nalini, "depressed and in tears because he was penniless", she recounts. He told her: "Mum, I miss you, I love you, and I want to come home. I'm heading back to Melbourne soon."

On 1 July, 1994, he withdrew cash from his Commonwealth Bank account. Since then, there has been no trace of him. His dole payments stopped around that time. So did the phone calls home. Friends in Lismore lost track of him.

"It's as if he's just disappeared into a black hole," says Nalini.

'Boys will be boys'

Nalini was already pregnant with Stacy when she and Conrad migrated to Australia in 1972, escaping ethnic unrest in their native Sri Lanka.

They arrived in Melbourne during a recession, "and we walked all day, knocking on every factory, looking for work... It was really tough," she recalls.

Eventually, Conrad, an architectural draughtsman, landed a job, and, after renting a series of places, the family settled in Rowville, in the south-eastern suburbs. Stacy was born on 23 August, and Christian 12 months later.

Nalini stayed home until the brothers were half-grown, writing articles and short stories, and taking in sewing from factories. The family spent holidays travelling in Victoria, staying in caravan parks, often accompanied by Conrad's mother, to whom the boys were close.

Two photographs on the wall of Nalini's Mount Martha home show Stacy and Christian, aged three and two, dark-haired and mischievous, in the Alpine High Country village of Bright, a favourite family destination.

Stacy was "a brilliant child, very talented, very smart", according to his mother. "He loved his reading. He was very clever with Lego, and played the piano and guitar.

"He was very sensitive, and he really loved animals. Once or twice he brought these sickly little kittens home, and we had to take them to the RSPCA to be put down. He had a very soft side to his nature."

He also kept the family entertained. "When he was nine or 10, Boy George was very popular, and Stacy used to do a great imitation of him," laughs Nalini. "He loved his rap dancing, too. Both he and Christian were into their footy – I think Stacy followed Geelong – and they played football every Saturday morning."

At school, Stacy excelled in history, literature and maths. He wrote poetry, and was keen on computers. For his 13th birthday, "we gave him this big, old-fashioned Commodore," remembers Nalini, "and it was so slow, he used to get really frustrated and say, 'This is a crap computer!'"

It was around that time that Stacy's sunny nature began to darken. Bullied at his Catholic high school, St Joseph's College, he often came home upset, relates his mother.

She reflects: "Stacy was very intelligent, but he could also be quite cutting. He was a Smart Alec and maybe the boys didn't like that. One day he came home crying because they'd put him in a dustbin."

Another time, on a bus, the bullies grabbed one of his precious Doc Marten boots – he had saved up to buy them – and threw it out of the window. Stacy was called names, too: "black" and "chocolate" and "Abo".

Nalini and Conrad voiced their concerns to the school principal, Father Julian Fox, who merely responded: "Boys will be boys." (Fox was jailed in 2014 for assaulting students.)

Formerly enthusiastic about school, Stacy became moody and uncommunicative. At home, he shut himself in his room and fussed obsessively over his food. He grew apart from Christian, and argued with his father constantly.

Sometimes, says Nalini, "he would get really angry and try to kick in a door or a window. Once, when he was 15 or 16, he and Christian had an argument, and Stacy tried to punch him. Christian ducked, and Stacy's fist went into the wall and he broke his little finger."

He was, she believes, mixing with a crowd that took drugs. In Year 10, he began staying out all night and missing school. "One morning his eyes were really red. I asked him, 'What have you been doing?' He started giggling, and said, 'I'm pissed, mum, I'm pissed.'"

Sydney and a Parisian bride

In Year 11, at Stacy's urging, his parents withdrew him from St Joseph's and enrolled him in another private school. However, he dropped out again, after just a term. He wanted to travel, he declared. Nalini and Conrad thought the experience might settle him down.

In late 1990, Stacy set off for Europe, where he spent a year, staying with Conrad's brother in Berlin and Nalini's sister-in-law in London.

While away, he began smoking cannabis, and also cigarettes, a habit he had previously disdained. Not long after returning to Australia, he decided to move to Sydney, where he hoped to join a band.

In February 1992, Conrad dropped Stacy at the Melbourne coach station, his only luggage a small bag and his guitar. The day before, the pair had gone out to lunch and to a movie, 'Total Recall'.

In Sydney, Stacy boarded in a rambling, eight-bedroom house in inner-city Darlinghurst, owned by a Filipino family. A friend was renting a room there, as were two Parisian students. Stacy waited tables in a local cafe, and played occasional gigs.

"He was a friendly sort of guy, and an aspiring artist," says Melchor Buenaflor, one of the Filipinos.

"He played the guitar and was studying flamenco guitar. We used to drink together at the Courthouse [a local pub]. I remember that he always wore a denim jacket, whatever the weather."

Stacy, Melchor recalls, was also "a bit naive, a bit too trusting of people". Once, he bought what he thought was marijuana from a man outside a pub in the Kings Cross red-light area – only to discover later that it was a bag of tea.

Every few months, Stacy would contact his parents – almost always needing money. They deposited modest sums in his bank account, and sent him cheques at Christmas and on his birthday. When they tried to contact him, though, he always seemed to be out, and did not return their calls.

On 23 May, 1993, Stacy married 19-year-old Sandrine Rigal, who was living in the Darlinghurst house. The brief ceremony was witnessed by Melchor's younger brother, Timoteo, and by Rigal's friend, Corinne Garraut.

According to the brothers, Stacy and Rigal were not romantically involved. "The wedding was done so she could stay in the country," says Timoteo. On 27 May, however, Rigal left Australia – and she has never been back.

Nalini remembers: "Stacy called me and said, 'Guess what, mum, I got married!' He liked to tease, so I thought he was pulling my leg. I said, 'Good, great, congratulations!'"

Later that year, or in early 1994 – it's not clear exactly when – Stacy left Sydney, telling the Buenaflors he was heading to Byron Bay.

"I think he said he was going to hitchhike his way up there," recollects Melchor. "He just wanted to travel. He took all his belongings with him – he didn't have much."

Neither he nor Timoteo saw or heard from Stacy again.

Life at Southern Cross University

In April 1994, when Nalini was still living in Melbourne, and working in a Centrelink (then Department of Social Security) office, Stacy phoned her from a DSS office in northern NSW.

"We had a long conversation. He was agitated, and he said, 'I'm sitting here alone, I haven't got any money, I haven't got anything.'"

That lunchtime, Nalini deposited $100 into his bank account. Eight days later, he called Conrad and told him: "Dad, I'm stranded in Armidale." As Conrad later relayed to police: "He told me he'd done a gig in Brisbane and was on his way back to Sydney in a car. He said his girlfriend got angry with him and drove off."

Stacy asked his father for the train fare. Noting that he would need money for food and lodging in Sydney, Conrad deposited $200 that day. Usually, when his parents topped up his account, Stacy would phone to thank them. This time, however, no call came.

Over the next three days, he gradually withdrew the money from an ATM in Lismore, where, unbeknown to his parents, he was now living. On 28 June, the DSS deposited $249 into his account – his fortnightly dole payment. He took out $100 on 1 July.

Police believe Stacy was actually in Lismore when he claimed to be passing through Armidale. They established that he hung around the Lismore campus of Southern Cross University, and even attended psychology lectures, although he never enrolled.

John Gillen, a computer science student, met Stacy in 1994 in the university bar, where both of them played pool. They became good friends, and lived together in a share house near the university for a few months.

According to Gillen, Stacy was a "fairly placid, easy-going person", who owned little more than "the clothes on his back", and "never spent any time looking for a job". Despite being perpetually broke, the pair "spent most of our time trying to have fun ... We spent our time and money on alcohol and cannabis."

Phillip Atkinson lived in the same house, as did Laurence Daniels. Daniels remembers Stacy as "a spaced-out kind of guy who was not stable and talked of demons and the like".

In Atkinson's view, Stacy was "a drifter ... [an] aimless lost kid who looked young for his age", and who liked drugs, but because of his limited funds was "not a heavy drug user".

For a while, Stacy apparently lived in university accommodation, sharing a unit with a Fijian woman, Seini Korovou, who was studying for a bachelor of tourism and hospitality.

On 12 May, 1993, he reported his backpack stolen from Lismore's Tattersalls Hotel. The bag, which vanished from a ledge, contained his passport, wallet, Medicare card, marriage certificate, bank card and $50 in cash, he told police – and also his student ID, he claimed, although he never enrolled at university or TAFE.

Curiously, Korovou – separately – reported losing her purse that same day, also in Lismore. Like Stacy, she gave her address as the university unit.

In the bar at Southern Cross, Stacy met another student, Shelley Smith, also a keen pool player. They hit it off, and soon Stacy was spending three or four nights a week at her flat.

The couple competed at pool evenings in the campus bar, and drank at Tattersalls. They had intense conversations about religion, spirituality and God. While Stacy was fun to be with, Smith recounts, and was "often a comedian", he had "a very dark side".

"He got violent a few times," she says. "He never got aggressive towards me, but would take his anger out on inanimate objects."

The last time she saw Stacy, they had an argument in her flat. He threw her bike helmet against a wall and overturned some plastic furniture. Then he "got very hysterical and started to cry", says Smith.

She comforted him, and they parted "on OK terms". But when Smith bumped into Atkinson a week later, he told her Stacy had moved out. She never saw him again, and was "upset that he had left without saying goodbye".

Stacy's disappearance shattered his father

Nalini's walls are covered in beach scenes and still lifes, as well as landscapes of Port Phillip Bay, across which she watches the big ocean liners glide each evening. She paints in an upstairs studio, still writes, and teaches the piano. "It helps to keep me sane," she remarks.

She and Conrad moved to Mount Martha in 2010 from Frankston, further up the Peninsula. In May 2014, Conrad died of motor neuron disease. Eighteen months later, Nalini was diagnosed with breast cancer. She is still undergoing chemotherapy.

Stacy's disappearance shattered his father, who was racked with remorse about their poor relationship. His anguish only deepened as the degenerative disease took hold.

"He used to get so upset and he would cry, particularly at Christmas. He'd say, 'Another Christmas gone by, and no news,'" relates Nalini.

To the day he died, Conrad clung to the hope his son would be found. A devout Catholic, he told police in 2006: "Every day I pray to God that Stacy is safe and well somewhere, and if he is not, I pray for his soul."

As she talks, Nalini leafs through Stacy's baby book and other treasured mementos: letters, drawings, school photos, hand-made birthday cards, a sheaf of poems.

While a comic drawing of the family dachshund, Dash, seems to reflect his light-hearted side, in one of the poems he writes of being in "a well of confusion", and of envying the "happy" and "ignorant" children playing in the street.

After Stacy called his father, supposedly from Armidale, Conrad phoned the house in Darlinghurst every day for a week. Each time he was told that Stacy was not back.

He and Nalini went to the police, only to be informed that "it's not a crime to go missing".

Conrad "resigned myself to the hope that Stacy would contact us". The couple urged friends and relatives in Sydney, including Nalini's sister, who lives in Mosman, to look out for him.

As the months turned into years, the de Sielvies despaired. In 1996, they contacted the Salvation Army's Family Tracing Service, but the agency's inquiries drew a blank.

They also consulted a clairvoyant, who told them she believed Stacy was alive.

'In my heart, something tells me he's alive'

A reported sighting of him in 1998, working at Darwin's Top End Hotel, was investigated and discounted.

The stress placed Stacy's parents' marriage under "terrible strain", confides Nalini. "It's something that's constantly between you, and there's no relief."

In 1998, the couple drove to Armidale, still believing it to be their son's last known location, but returned home little wiser.

In 2000, their hopes were raised and dashed again, when a letter for Stacy arrived at his uncle's home in Berlin. It turned out to be a routine mail-out by the local Catholic diocese.

For Nalini, such events have been "the worst part of it – you're going up and down on a rollercoaster".

She worries that Stacy may have joined a cult, or suffered memory loss, or even met with foul play while hitchhiking to Melbourne.

After the 2006 re-investigation, carried out by Detective Sergeant David Mackie, Shelley Smith read about the case in Lismore's 'Northern Star'. She had had no idea that Stacy was missing. She contacted police, and also wrote to his parents.

An inquest was held in 2008. But Mackie still keeps Stacy's case papers in his office in Casino, in northern NSW.

"Most matters, when you've finalised them, they get filed," he says. "But this is one of those mysterious ones."

He still hopes to trace Sandrine Rigal and Seini Korovou – the latter returned to Fiji in 1998, then in 2007 moved to the US, where Interpol has yet to track her down. Rigal is believed to be in France.

Nalini frequently dreams about Stacy still. "In my dreams, he's usually a child of about eight, and he's talking to me. Then I wake up to the reality that he's not here, he's been missing all these years.

"I had one very vivid dream where I was walking down a street in the neighbourhood and I came face to face with him. I said, 'You've been living around here all this time and I didn't find you!'"

Sometimes she re-reads Stacy's poetry, "trying to get an insight into what was going on in his head".

And while she can't imagine him letting so many years go by without making contact, she still harbours hope.

"Look at all those missing persons out there, and some are found after 30 or 40 years," she says. "In my heart, something tells me that he's alive somewhere."

If you have any information regarding a missing person, please contact Crime Stoppers on 1800 333 000.