Attila's car was found in Picton NSW

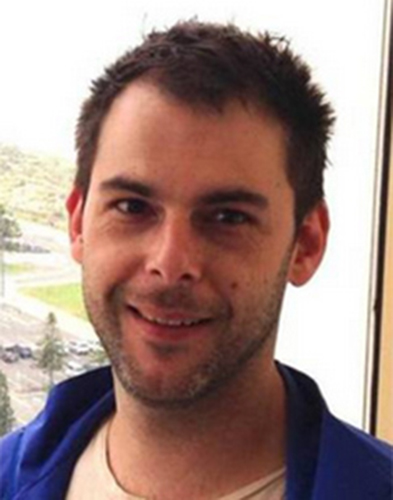

Attila and his partner Jason

On 9 October 2014 Attila Bogar attended his mother’s address

in Avondale Heights Victoria. He was in a distressed and paranoid state.

Attila then left the address in the evening and drove his vehicle towards

Sydney. He made a phone call to his family from Sydney on 10 October 2014

saying he was heading home and was just getting something to eat.

He has not been seen or heard from since.

On 17 October 2014 Attila’s vehicle was located abandoned near bushland on

Picton Road, Picton NSW with his belongings inside.

Police and SES conducted extensive searches of the surrounding bushland

which were unsuccessful.

If you have information that may assist police to locate Attila please call

Crime Stoppers on 1800 333 000.

A week-long search in bushland near Cataract and Cordeaux dams has failed to find any trace of a man whose car was found abandoned on Picton Road last Friday.

Attila Bogar, a 35-year-old man from the Melbourne suburb of Avondale Heights, was last seen on October 9.

Police believe Mr Bogar may have been in Wollongong on October 10.

A multi-agency search for the man was sparked on Friday October 17 by the discovery of his car - a grey Audi Q3 - on Picton Road at Cataract.

Members of the police rescue squad and the State Emergency Service scoured the area over the weekend and all this week, but have not located Mr Bogar.

Carly Heard, a friend of Mr Bogar, contacted the Mercury on behalf of his family to plead for any information on his disappearance.

‘‘His friends and family are concerned for his safety. We appeal for anyone who knows something, or for Attila, to contact police,’’ Ms Heard said.

‘‘He is a very family-oriented man with lot of friends.’’

Ms Heard said Mr Bogar may have been in NSW searching for an old family friend who lived in Sydney.

Police have also appealed to the public for information.

‘‘We are concerned for his welfare, and an investigation is underway into his disappearance,’’ said Wollongong police crime manager Inspector Tim Beattie.

Mr Bogar is described as being 180centimetres tall with a medium build, dark brown short hair, and an unshaven face. He is believed to have been wearing jeans and a t-shirt at the time of his disappearance.

Anyone with information about his whereabouts is urged to contact Triple 0 or

Crime Stoppers on 1800 333 000.

The disappearance of 38,000 Australians every year leaves their families and friends in an agonising web of unanswered questions, writes Lawrence Money.

"I'm all right," Attila Bogar told his mother Roza when she phoned him anxiously at 10 in the morning. "Sorry, I've got to go and get my medicine and have something to eat."

Such unremarkable words but 74-year-old widow Roza Bogar still clings to them. They are the last thin thread to her 36-year-old only son – he was in Wollongong, it was Friday, 10 October 2014, and the Bogar family have not heard from Attila since.

A loving brother to 30-year-old sister Maryann, Attila vanished somewhere along the Princes Highway, two days after he made a peculiar overnight trip to Sydney from his Moonee Ponds home.

He headed back to Melbourne almost immediately, reaching Wollongong on 9 October, but his silver Audi 03, registration ZGB 609, was found later, abandoned on a rural road. His iPad, laptop and mobile phone were inside.

Where is Attila Bogar? The mystery darkens every waking hour for his family and friends, just as it does for those close to the 38,000 other Australians who go missing each year. Statistically, that is about one person each 15 minutes, leaving a network of loved ones in a nightmarish web of unanswered questions. Where? Why? How?

Again and again the Bogars ponder that strange chain of events leading up to Attila's disappearance. The young IT businessman, normally outgoing and sociable but on medication for anxiety since 2006, had recently become reclusive.

He had stopped driving his car and phoned mother Roza around midnight on Wednesday 8 October, asking her to drive over and take him to her house in Avondale Heights, ten minutes away.

Roza did so, making him a cup of tea upon arrival. He declared he would sleep the night there, went to the spare bedroom, switched on the TV then made a phone call. It was around 1.30am. "Who are you talking to at this time of night?" asked his mother. "I know what I'm doing," he replied.

Minutes later he declared that he wanted to be taken home again. He asked Roza if he could borrow $500 for "accommodation". What sort of accommodation, she asked. He would not explain.

Half an hour after Roza gave him $250 and dropped him back home, Attila climbed into his car and set off for Sydney, apparently looking for, but failing to find, a family friend there.

This was the same Attila who had not driven his car for a month, who had been unwilling even to drive the ten minutes to his mother's. "It makes no sense," says a tearful Roza Bogar.

At least one small piece of the puzzle fell into place – a week after the disappearance, a parcel arrived in the mail for her. It was a new cordless phone with emergency pendant for the elderly. Attila, having seen it advertised on television that fateful morning, had ordered and paid for it in that unexplained phone call he made at 1.30. "He has always been a thoughtful boy," his mother says.

The Attila Bogar saga is a familiar one to 30-year-old Loren O'Keeffe. For her Melbourne family, the ordeal began more than three years ago when her younger brother Dan vanished. There was a tantalising sighting of him in Queensland six months later, captured on CCTV at the Grange Road medical clinic in Ipswich, but despite the most intensive of publicity campaigns by his sister, no report or word since.

O'Keeffe is a remarkable woman. Highly driven and innovative, she was surprised at the time of her brother's disappearance by what she saw as a woeful lack of guidance for her family as they entered a world where no-one wants, or expects, to go.

"You can find anything on the internet these days," she says. "YouTubes on boiling an egg or tying your shoelace. But there was nothing to advise you what to do if someone goes missing. When I asked the police that morning they couldn't give me any direction. It was absolutely absurd."

So O'Keeffe left her job with the Victorian public service to set about creating her own publicity campaign using the internet, social media, posters, phone calls, any means available. She dubbed it Dan Come Home, still active as the search for him continues, but it has also been the catalyst for something much larger.

The skills she learned along the way eventually prompted O'Keeffe to set up the Missing Persons Advocacy Network (MPAN), now a registered charity and a go-to site for families when a relative disappears. With no job, it has been a financial struggle for her -- she has had to use savings, a "social responsibility" grant from Vodaphone and one $10,000 private donation which has just been depleted -- but Loren O'Keeffe has turned MPAN into a new career. "It's bigger-picture stuff now," she says, "not just about Dan.

She set up an on-line Missing Persons Guide with all the information she had needed, but did not have, when her brother disappeared - who to report to, how to create a "missing" poster, advice on media exposure, recruiting volunteers, reporting, managing the missing person's financial affairs, getting legal support and much more. This week, backed by the Singapore-based Grey conglomerate, she launches a world-first initiative - Help Find Me - using the search boxes of corporate websites.

It was a friend of Attila Bogar who phoned the Dan Come Home hotline a few weeks ago to seek advice. Although police play the main role in searching for missing persons, organisations such as the Red Cross and Salvation Army also help.

Major Sophia Gibb has headed the Salvation Army's family-tracing service in the southern and western states for nine years. "We don't get involved until someone is missing for at least three months," she says. "We search for at least 500 people a year and find about 70 per cent. We reunited a father and son recently. They had not spoken since a tiff six years ago. The father wanted to reconnect and we found the son – he was living in the same Melbourne suburb."

Gibb says marriage or relationship breakdown is often a trigger when someone goes missing. "One spouse goes searching for the other spouse. Or children want to find their father who, perhaps, has not been on the scene. There are a lot of fathers who pay custody but don't get visiting rights. Get quite a lot of that.

"Lifestyles are another reason. Where someone declares homosexuality which is not accepted in a lot of families. There are people on drugs or alcohol. Because of drugs a lot of people have schizophrenia."

Even when the Salvation Army finds a missing person they can sometimes be classified "located only" because, unless the missing want to be found, no information can be passed on.

"Sometimes, when we hear the other side of the story it is no wonder the person has gone missing," says Gibb. "Family violence, child abuse, sometimes the missing person never wants the relationship reopened. We don't pass out anything without permission of the person sought. We have to be very careful these days with the Privacy Act."

In fact privacy legislation in the various states and territories of Australia can prove an obstacle. Because it is not a crime to go missing, even police have had difficulties in obtaining details from such sources as banks, Medicare, Centrelink or the Australian Tax Office, details which might indicate (a) that a missing person is still alive and (b) where that person may be.

An Institute of Criminology report in 2008 estimated that that wading through such privacy red tape could take police up to two weeks. However the head of the Victoria Police's newly formed Cold Case and Missing Persons squad, Detective Senior Sergeant Boris Buick, says this is no longer the case. "The privacy provisions don't prevent us from doing our role," he says.

Conversely, police can be surprisingly reluctant to disclose information on a case, even to the families of missing people. Loren O'Keeffe says her mother was denied permission to view CCTV tape recorded the day Dan went missing - believed to show him outside a cinema in Geelong.

There was an inexplicable policing failure six months later when a woman working at the Ipswich medical clinic recognised Dan in a TV segment on his disappearance. He had been the man calling himself "James" (Dan's middle name) who had come in to the clinic two weeks earlier asking for a glass of water.

The woman phoned Crime Stoppers but the O'Keeffe family was not advised. Two weeks later the woman phoned Crime Stoppers again to see if her report had led to any breakthrough - she was told no information could be disclosed. That was when the woman called the Dan Come Home hotline and Loren flew up to Queensland.

"I didn't tell the police because I thought they might prevent me viewing the tape," says Loren. She confirmed it was her brother although he was in a bad way. "He had lost about 30 kilos and looked like death," she says. She obtained a copy of the tape but has never released it publicly, believing Dan might see this as an invasion of his privacy.

It was an eerie feeling – watching the brother she had not seen for six months, talking to two women at the clinic. He told them he had been sleeping in parks and was now heading for Brisbane. Loren then spent two months searching parks and homeless shelters in Brisbane and Ipswich: "We asked for the case to be transferred to Queensland where he was last seen," she says, "but Victoria Police said there was no concrete evidence that it was Dan."

For the O'Keeffes, there was no doubt – Dan was familiar with that medical clinic, having taken his girlfriend Susie there (Ipswich was her home town) on more than one occasion.

Buick insists that the various state police forces do co-operate and exchange information. "I'm familiar with the Dan O'Keeffe case. We asked Queensland police to investigate but it came to nought. It remains a Victorian case because he's missing from Victoria."

Buick said uniformed police handle the bulk of missing persons cases in Australia. His squad becomes involved only if there is suspected homicide. "But there will be times when investigators aren't able to pass on some of the information [to the public] because that information has been gleaned in the capacity of a law enforcement body."

Loren O'Keeffe refuses to give up hope for her brother who would now be aged 27. "I like to think that Dan is perhaps living with like-minded souls, somewhere beautiful in some alternative commune-like set-up," she says. "He had turned to Tibetan Buddhism before he went missing. One theory was that he was going on some sort of spiritual journey."

In Avondale Heights, Attila's silver Audi is parked in the driveway of his mother's home. Roza Bogar and Carly Heard, a close friend of Attila, brought the vehicle back to Melbourne after making their own inquiries in Wollongong.

It has been a very tough 12 months for Roza, who migrated to Australia from Hungary in 1971. Her husband Jimmy, whom she met in Australia in 1977, died last April. Jimmy was a meat worker who had migrated in 1957. After he became ill with liver problems Attila researched and monitored his father's diet and ensured he exercised. He had solar panels fitted to his parents' house to reduce their expenses. He organised a houseboat holiday for the family in Jimmy's last few months. At his firm Net Business, he used to pay a masseuse to give a weekly massage to staff. When one of them was going through hard times, he paid for a domestic cleaner. Generous, hard-working, meticulous, a devoted son. "Everybody loves Attila, that's for sure," says his mother. But where is he?

The vanishing

About 38,000 Australians go missing each year

Up to 12 other people (family, friends) are severely impacted by each disappearance

In 2006 (most recent stats) national Missing Persons rate was 1.7 per 1000 population

In 1998 the national rate was 1.6

Highest regional rate is in the ACT (3.3)

More than 90% of Missing Persons are found within 48 hours

Two per cent are still missing after 6 months

Source: Aust Institute of Criminology report No 86; Vic Police missing persons squad 2015

IT’S been almost two years since he vanished, but not a day goes by that Rozalia Bogar doesn’t hold hope her son Attila will walk back through the front door.

NOT a day goes by that Rozalia Bogar doesn’t hold hope her son will walk back through the front door.

Attila Bogar hasn’t been seen since October 9, 2014, after a distressed visit to his mother’s Avondale Heights home in the middle of the night.

She picked him up at midnight, at his request, but after just half an hour, he asked her to take him back home – it was the last time she saw her son.

The family later found out Attila had driven to Sydney that night, phoning the next day to let them know he was on his way home.

But then all correspondence stopped.

“We called every minute, every half an hour,” Mrs Bogar, pictured, said.

“My friends and everybody called him, and no answer.”

Mrs Bogar said she couldn’t see why her son, a “very good boy”, would disappear.

“It was very strange to just have left and say nothing, not to (his) friends, not to me,” she said.

“That’s what I’m hoping for – that one day he’ll turn up.”

Eight days after Attila was last seen, Wollongong police found his car and all his belongings abandoned near bushland on Picton Rd, in NSW.

NSW Police has theories about what happened to Attila, who suffered anxiety, but hasn’t had any leads for some time.

His case has been referred to the state coroner.

“Evidence from family, friends and the investigations suggest mental health issues may have been a factor in his disappearance,” police said in a statement.

Attila, who would be turning 38 in November, is described as caucasian, about 180cm tall, with a medium build, brown hair and brown eyes.

He has a mole on his left cheek.

Phone Crime Stoppers on 1800 333 000 with information.