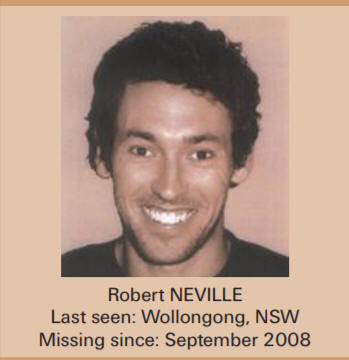

WHEN Bob and Sue Neville take to the road, it's not for pleasure - they're

searching for their missing son.

Coledale parents still hold out hope for

missing son

Updated July 30, 2012

10:05:43 - ABC

It's national missing persons week, and the parents of a missing

Coledale man say their son's bush survival skills give them hope that he may

still be alive.

Sue and Bob Neville say their only son Bobby had been battling bipolar

disease prior to his disappearance in September 2008 at the age of 30.

But they also say he was a keen diver and fisherman, was making bone

fishing hooks, and had the knowledge and skills to survive in the bush and

desolate areas.

Bobby Neville's mother Sue says he once built a canoe out of a fallen

tree on the Illawarra escarpment and survived trips to remote areas of

Australia.

"He had been on a number of trips right up to the cape and he actually

did manage to survive quite well", she said.

Bob Neville says he still hopes to one day get a phone call from his

son.

Missing: broken hearts keep asking why

This story first appeared in the Mercury on June 2, 2013.

Three years after his son went missing, Norm Stanton found himself walking

the paths of a Buddhist monastery poised on the edge of the Morton National

Park.

As he walked and meditated on his loss, he heard the words repeated like a

mantra inside his head:

"I'm still with you, Dad."

This was the moment when he could walk no more, when he found a log, when he

collapsed and sobbing engulfed his body.

"I felt there was an element of truth," Stanton, a retired primary school

principal, said.

"His presence was with me even if he is missing, Ian's memory is still with

me in my head and heart, and I thought, 'Let's inscribe it on my body and

get a tattoo'."

So it was that, a few weeks ago on his son's 33rd birthday, Stanton found

himself sitting in a tattoo parlour for his first piece.

Rolling up his sleeve, this gentle, thoughtful, sad and compassionate man

reveals the blue-black ink still fresh on his skin:

"I am still with you Dad." The Grebe.

Ian Stanton was a challenging son, who carried the family nickname of a bird

whose portrait appeared on a stamp when he was a baby - a bird with a small

tuft of hair like his own.

He was adored and happy as a child, but started smoking marijuana as a young

teenager and later became so difficult that he left home for a refuge before

he was 17 years old.

Probably an undiagnosed schizophrenic, he led a chaotic life. He grew dope

and may well have sold drugs for a while.

Sometimes he worked, sometimes he did not. Sometimes he had a girlfriend,

but none lasted. He developed a heroin habit for a while, but kicked it.

He was a WIRES volunteer, was artistic, became an amateur actor and

community radio announcer.

He was a talented cartoonist and - at his best - gentle, funny and clever.

The last time the family were together was a happy occasion, his 23rd

birthday, but a week later he was short and dismissive when his father

turned up at his home in Bundanoon to deliver some mail.

A week later, he was gone - no-one knows the precise date of his

disappearance - and, like 12,400 people every year in NSW, he was reported

missing.

His sister, Alex Speed, later described the experience as "living with a

permanent bruise under our skins".

The first and most important fact to realise about missing people, according

to Chief Inspector Paul Roussos, manager of the Missing Persons' Unit in

Sydney, is that the vast majority turn up again.

Of the 12,400 reported missing, only about 30 people remain missing after a

year - though some are found dead through accident, suicide or misadventure.

"If you have a concern for someone's welfare, then that starts to become a

missing person matter," Roussos said.

"That's why we say, if you have a concern for a person then report it, don't

wait.

"It's important not to wait because if there is foul play, or if something's

gone wrong, it's important to have the authorities on the matter as quick as

we can."

If police treat reports of missing people differently now, it may be partly

due to the efforts of Stanton, who tells his family's story to all new

recruits passing through the NSW Police Academy at Goulburn.

It would be fair to say, however, that the Stantons' experience was not a

good one.

"I say to cadets 'Don't treat people like I was treated. Don't make

assumptions that that person is going to turn up'," Stanton said.

"When I reported Ian missing at a police station, the officer didn't take

any details and just fobbed me off. It was a really lazy approach."

Worse still, there were only cursory search attempts at the most likely

location for Ian, the Morton National Park, where he used to go for long

rambles through the bush.

So Stanton, his wife Jean, and other family members found themselves bashing

through the undergrowth in a desperate attempt to find Ian.

"Those early days were heart-breaking stuff, not knowing what had happened,

not knowing what to do," Stanton said.

"We did our own searches but we're not bushwalkers and we're not trained to

do it."

They eventually stopped when they realised they were lost in the bush, and

saw the irony of the parents of a missing son going missing themselves.

It was up to Stanton to ring police stations, refuges, hospitals and mental

health institutions in a vain attempt that any had seen his son.

Even now, Stanton hands out photos of Ian when he talks to service clubs,

because, as he says: "You never know".

You never know.

Stanton calls it the Clayton's Loss - after the non-alcoholic drink

advertisement, whose line was "The drink you have, when you're not having a

drink".

"For me, this is the loss you have when you don't really know if it's a

loss," Stanton said.

And that is the point.

That, according to Liz Davies, the co-ordinator of the Family and Friends of

Missing Persons, is what makes the fact of a missing person so hard.

The group is the only one of its type in Australia, and was founded in 2000

after lobbying by families of missing people and is funded by the state

government.

Quoting an American expert, she calls it "ambiguous loss" for that state

when a loved one is both psychologically present but physically absent.

"The struggle for families is finding a way to sit with not knowing," Davies

said.

"They have to find a way of living with the ambiguity of the missing person.

"The recipe is a very challenging one.

"We talk with families about finding a place of comfort with themselves, of

sitting with the not knowing and lack of clarity, of being able to move

forward with their lives.

"If you come at missing from a problem-solving, solution-focused

perspective, it confounds you.

"There may be no solution, though we would love for it to be possible.

"The solution is that the person returns, so families work to find a way of

waiting that is tolerable, to find a way of living with not knowing."

The group provides a range of support, including helping support groups such

as the one that attracts up to a dozen people to share experiences every

couple of months in Corrimal.

"I don't believe we have the right to ever say to a family that there is no

hope," Davies said.

"I don't believe families ever give up hope, though the nature of their hope

might change."

Yet hope is no simple proposition.

Bob and Sue Neville have travelled around

Australia, looking for their son, Bobby.

No-one knows this better than Bob and Sue Neville, whose son left the family

home in Coledale with the words: "I'm just going for a walk, Mum".

That was one warm September day in 2008, leaving behind him parents

tormented by questions that may very well never find an answer.

It was not unusual for Bobby to leave, though he would always be in touch

eventually, but this time, Sue felt a mother's intuition when walking the

next day with Bob.

"I just had this overwhelming feeling that he's not coming back and that

something had happened. I almost dropped to my knees," she said.

Is he alive? Is he dead? Would he leave without explanation? Does he want to

be found? Did he kill himself?

Bobby Neville’s boat is still in their yard, last used a couple of weeks

before he left.

His old bomb of a car waits for the return of its owner. The fence and the

sandstone terrace he built on the property are reminders of his presence.

‘‘He is so embodied in our property that we stay, even though our property

is getting very difficult for us to manage now,’’ Sue, a retired teacher

from Figtree High, said.

Like the Stantons, the Nevilles are torn apart by the love for their child

and have only lately learned that they sometimes need to put him to one side

if they are to retain their sanity.

Bob is a retired draftsman and courier, a bearded bush character who is a

straight-talker and a man proud to set his own course, but in constant

physical pain from an old work injury.

The mental pain, too, is becoming hard to mask or to endure.

Bob admits that the void is ‘‘tormenting to the extreme’’ and that he’s

finally made an appointment with a counsellor to get help.

He reveals that he is on medication to settle him down for the interview

because, that morning, he was ‘‘shaking like a dog shitting razor blades’’.

‘‘Sometimes, I talk to him while I am doing things, it’s just a thing we do,

like going to the grave and putting flowers there,’’ Bob said.

‘‘I had got to the stage where I’d tell him I’d have to go away for a week

or two – ‘You look after yourself and I have something I have to do’.

‘‘I have found the spectre of it is too great at times.’’

This is the dark side of parental love, revealed by the constant and

desperate searching of two parents who would give anything to hold their son

in their embrace once more.

The Nevilles have travelled all over Australia in search of Bobby.

They’ve been to Adelaide, travelled the Ghan to Alice Springs, driven up to

Queensland and the NSW North Coast.

They would turn up to police stations, caravan parks, taxi ranks – anywhere

– always armed with flyers showing photos of Bobby.

Every time their hopes are raised with a possible sighting, or the discovery

of bones in an outback grave, they are smashed once more.

One time, they had only just returned from a trip up the North Coast when

they received a phone call from a caravan park owner who reckoned she had

seen him.

It sounded hopeful – a man with a skateboard under his arm, talking about

fishing and wondering if he could have a shower and a coffee.

So Sue turned right around again, seeking leave from her job, and travelled

for five hours to Laurieton.

When she arrived, she showed the owner more photos of Bobby and suddenly the

certainty faded. Maybe it wasn’t him after all.

But hope would not stop tormenting the parents, so they returned six months

later and traipsed seven kilometres up the beach, searching the scrub where

homeless young men were living rough.

The adrenaline of hope pushed Bob on until he remembered his pain and knew

he could not return, hoping only that there would be help further on.

‘‘You do lose your equilibrium and that’s where I am at the moment,’’ Bob

said.

‘‘It’s not good is it? I have lost my equilibrium, I bloody have.’’

Because another strange torture of missing is that – in many ways and in

contrast to other forms of grief – it becomes harder to bear over time.

Another member of the Corrimal support group is Karen James whose father,

former serviceman and taxi driver Leslie Hicks, vanished shortly after

breakfast on Easter Sunday, 2008.

He left his Woonona retirement village on a short walk to his daughter’s

house and has never been seen since.

For three years, James was convinced her father was alive, despite that fact

that he was nearly blind and needed daily medication for his diabetes.

She believed he may have forgotten she was away at her caravan down the

coast that day, and instead attempted the journey to his son’s house on the

mid-North Coast.

It took three years for her to buy a burial plot at Kembla Grange – her hand

was forced because they were selling fast and she wanted him buried near her

mother, who died in 1989.

‘‘That was when I started to accept that I had probably lost him,’’ James

said.

‘‘I wanted some place to go, but I have nothing to write on the headstone

because I have no date of death.’’

James only found out about her father’s disappearance on the Easter Monday,

and still regrets those 17 lost hours when he was gone but not yet reported

missing.

Like the Nevilles, she has had hopes raised and then dashed.

‘‘If I am driving, I am still looking the whole time,’’ she said.

‘‘If I see an old man the right height, if I can’t see him properly, I have

to do laps until I can get a good look. I am always on the lookout.’’

She’s been to see three clairvoyants, but has never had a message from the

other side.

One saw his body in thick lantana and brambles in bush between the Bulli

Pass and Pope’s Road, where he used to live.

But when police searched the area, they found nothing.

Until the past few months, James was reluctant to leave the house in case

she missed a phone call from her father and medication to combat anxiety has

increased in strength as time passes.

‘‘It’s funny, because when you lose somebody from death, it gets easier

every day,’’ she said.

‘‘Because you have put them to rest, and you know they’re gone.

‘‘With this, as time goes on it gets harder. You think about all the

what-ifs.

‘‘The hope starts to fade and you wonder if there might have been foul

play.’’

She hates the rain or when it’s really cold because the part that thinks

he’s still alive worries that he is cold. The part that thinks he is dead

doesn’t want his body laying out there.

‘‘I feel despair,’’ she said.

One of the men in the Corrimal group recently heard that his wife’s remains

had been found and the other people congratulated him.

The wait was over, even if the questions were not.

But although James would welcome the news that her father’s body had been

found, she knows that would not be the end.

‘‘Everybody says that you’ll have closure, but that’s a word I hate,’’ she

said.

‘‘You won’t have closure because you don’t know what happened.

‘‘You don’t know how they died or what they went through.’’

The only truly happy ending for any of these families would be if their

loved one walked in through the door.

And even then, the questions may never have answers that satisfy.

Blog: How to live with a missing son

Robert Neville (Bobby) had been away from

home on several long outback trips over the years, but Sue

Neville never expected her son to disappear from her life.

Our son, Robert Neville (Bobby) had been away from home on several long

outback trips over the years, but we never expected him to disappear from

our lives.

Bobby has been missing since 30 September 2008 after telling me he was going

to the beach for a walk. The initial police response when he didn't return

was disappointing: “A 30 year old man should be OK”. But we knew something

was very wrong and out of character by the time we officially reported him

as missing.

With police unable to find him, my husband Bob and I decided we would try to

locate Bobby ourselves. We bought a caravan so we could travel around

Australia to look for him. Our search soon led us to most corners of the

country: Perth, Darwin, Alice Springs, Lake Eyre and Lightning Ridge, to

name a few. We took our NSW missing persons poster to police stations across

Australia to remind the officers that we had not given up. Often they

responded positively, organising meetings, checking their databases and

putting out further alerts that Bobby could be in the area.

Sometimes, however, the response was less helpful. Early on in our travels,

we discovered that there was little communication between the different

states about missing persons. This confusion greatly concerned us, as hope

of finding Bobby is all we have left. In fact, hyper-vigilance becomes a way

of life when you're uncertain what has happened to someone, and it is

exhausting.

Even today, nearly five years later, I still find myself searching faces in

a crowd, particularly as I live near the beach where so many young men are

the same age as my son. I think I see him most days. It even resulted in me

having a car accident when I became distracted after I thought I had seen my

son on the side of the road. From that moment on, I have had to remind

myself to stop constantly searching for him, to concentrate on the present

moment. It also helps to say to myself, “well, if that was him driving the

other way, or walking along the street, then he is alive, and that's all I

need to know.” I do know that subconsciously, I'm still searching.

I stopped taking the caravan trips and searching physically for Bobby in

2011. We had information that there had been a sighting in Port Macquarie.

As we walked along a beach searching for him, we became lost both physically

and emotionally. In that moment, I suddenly felt a calm come over me for the

first time since Bobby went missing. It was then that I decided that Bobby

probably wasn't alive and that I would stop taking the trips to find him. I

realised that if he had died, at least he was OK.

Everyone reacts differently – my husband is still planning trips to find

Bobby. He copes by believing Bobby is still alive, somewhere out in the

outback where people can hide if they don't want to found. This poses its

own difficulties as it is hard for my husband to understand why our son has

not been in touch.

It is increasingly difficult to live with a missing loved one. No one wants

to lose a child but the unresolved grief really cuts away at your spirit.

The grief we live with is unlike the grief when a loved one dies. I don't

mean to dismiss such grief, but when your loved one is missing, there are no

answers. It's an ambiguous loss because they're not here physically. There

are challenges with having an adult child go missing too – adult people have

the right to privacy and to live their own lives, but when they are part of

a close family like ours, you expect them to be in contact. You find

yourself wondering if he is the man you thought he was.

I have found comfort in a support group called Friends and Families of

Missing Persons Unit (FFMPU). We meet with people who know what it is like

living with missing loved ones. Other families and friends of missing

persons have shared their stories and also have discussed their

disappointments and concerns with the national system for finding their

loved ones. However, through the FFMPU we have seen some evidence in the

past few years of police training and development for dealing with missing

persons. New cadets are now given an insight into the importance of keeping

the lines of communication open, listening and responding to family

concerns. Hopefully, the police response will improve.

As a retired textiles teacher, I have found sewing circles often help bring

people closer together and a quilt can be a way of expressing ones self.

Recently, I have encouraged people to design a quilt square that brings back

happy memories of their missing person, enabling us to express our love,

embrace our missing person and announce our concerns to the wider community.

The quilt will be legacy to my son, and the sons, daughters, fathers and

mothers of a number of people from FFMPU – we have no headstones to visit.

Appeal to find Coledale's Robert Neville during National Missing Persons

Week

The case of missing Coledale man Robert "Bobby" Neville has been

thrust back into the limelight with a renewed appeal to find him.

Mr Neville's disappearance is one of 15 people who have gone missing

over the years from the Wollongong area.

August 4 to 10 marks National Missing Persons Week which aims to

raise awareness of the impact a missing people has on family and

hopes to reduce the number of people who are missing.

Bobby Neville was 30 years old when he returned to his family home

in Coledale on September 29, 2008 after a visit to Western

Australia.

The following morning, Mr Neville told his mother Sue he was "going

for a walk" and never returned.

There have been unconfirmed sightings of Bobby around the country

but Wollongong Police District investigators have received no

further leads as to his whereabouts.

Bobby, who would now be 41, is described as having a tan complexion,

about 183cm tall, and slim build.

At the time of his disappearance he had dark, short wavy hair and

suffered from a medical condition.

Police conducted a thorough search for Bobby, ranging from foot

patrols around the neighbourhood to interstate data matching

inquiries, but it was to no avail.

His heartbroken parents, Robert and Sue Neville, spent countless

hours over the years travelling around Australia in search of Bobby.

In 2013, Deputy State Coroner Geraldine Beattie could not rule out

the possibility Mr Neville could still be alive.

Robert Neville snr, told the inquest he firmly believed his only son

was still alive because he had the skill set to live off the land.

However, Mrs Neville could not believe her son could go so long

without getting in contact if he was still alive.

Ms Beattie ruled out suicide and Mr Neville's case will remain open

and active with NSW Police.

Last month NSW Police announced the establishment of a new unit to

investigate and coordinate long-term missing persons cases.

Following a review, Project Aletheia, a State Crime Command-led

initiative has been created. It will dissolve the Missing Persons

Unit and a new Missing Persons Registry will be created.

A team of seven detectives and four analysts - including those with

qualifications and expertise in psychology and data matching - will

work to resolve current long-term missing person cases.

Insight, Missing

Transcript

JENNY BROCKIE: Bob and Sue, your son Bobby disappeared five years

ago. I'm interested in what you did to try and find him and why you did some

of the things that you did. I mean you travelled, you've travelled all over

Australia, haven't you?

SUE NEVILLE: We have a caravan and so we've packed up many times and left on

our trips to try and find him. We've been to the centre of Australia, we've

been to Lake Eyre, we've been to Perth, to Albany, we've been all around New

South Wales up and down the coast.

JENNY BROCKIE: And you made up posters of him?

SUE NEVILLE: So we would take posters around to police stations and leave

them there and then they often would know all the people in the town, they'd

know if there were any newcomers to the town and we found that one of the

most efficient ways.

JENNY BROCKIE: But when you went from state to state you realised

that the other states didn't know?

SUE NEVILLE: No, that's right and so we realised we'd need to do a lot more.

But also in this time we've joined the Family and Friends of Missing People

and we found that through educating the police and through a number of

reasons, I suppose, they seem to be improving a lot and our last trip over

to Perth we actually went into the police station there and here was a

picture of Bobby on the wall so we were really pleased that things are

improving, maybe not fast enough for our son.

BOB NEVILLE: Yeah, and at that visit at Albany.

SUE NEVILLE: Albany as well.

BOB NEVILLE: The policeman in charge there, he had computer knowledge as

well and he talked us through it and he said look, what I'll do for you is

I'm going to put it in motion and get in touch with all of our police

stations throughout the state and when they turn the computers on, it was

late in the afternoon, the evening, he said the first thing they see when

they turn on tomorrow is this.

JENNY BROCKIE: But this is, this sounds like it's very much

dependant on an individual police officer actually doing that?

BOB NEVILLE: It is. Some of them are - if you go in there and if it's their

lunch time and they're having a sandwich, they'll tell you to go to buggery.

Just like that. And you know"¦

SUE NEVILLE: We met all sorts of people.

BOB NEVILLE: I've had some ding dong blues with them but I mean, by the same

token"¦

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

JENNY BROCKIE: Sue, what did you want to say?

SUE NEVILLE: Yes, I just wanted to add at that stage of the conversation you

become hyper vigilant. Everywhere you go you think you see them. My son, our

son Bobby is missing, he's been missing for five years, almost five years

now, and I've, I've had to stop the car, pull up, get out of the car, walk

up to someone and I've come within this distance, between you and me, and

until I was really close I still thought it was him. It's something you have

to turn off. I actually had a car accident as a result of being hyper

vigilant and that's what me stop and think and say I'm not going to find him

that way and anyway, if that is him he's okay.

BOB NEVILLE: She nearly killed herself, she did.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

BOB NEVILLE: Yeah, but it doesn't just stop there. Because you say"¦.

DET. SNR. SGT. RON IDDLES: No, it doesn't stop there.

BOB NEVILLE: No, so don't make it so pointed that when you say or you make

up your mind that he's dead or deceased"¦.

DET. SNR. SGT. RON IDDLES: No, I don't make it up. The Coroner makes it up

on the balance of the evidence that I"¦.

BOB NEVILLE: I know, from the evidence, from the brief that you provide.

DET. SNR. SGT. RON IDDLES: But that doesn't stop us from looking or working.

JENNY BROCKIE: It's a very difficult situation on both sides in a

sense, isn't it?