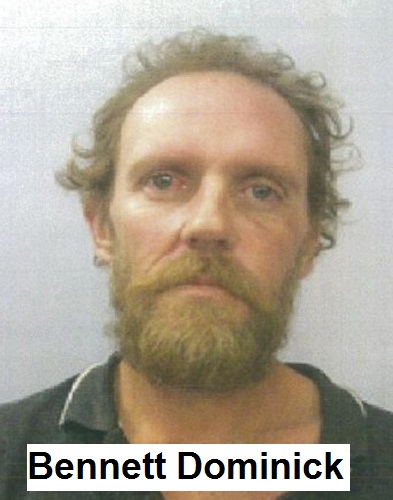

Bennett (Ben) Campbell DOMINICK

Bennett (Ben) Dominick was last seen on Saturday January 10, 2015 at a friend’s camp at the Coocoran Opal Fields in Lightning Ridge. His green, Ford Futura sedan was located several days later in bushland near to a substation in Lightning Ridge. He has not been seen or in contact with family or friends since this date and efforts to locate him have been so far unsuccessful. Police continue to hold grave concerns for his welfare.

Anyone who has any information relating to the whereabouts of Bennett Dominick are urged to contact Crime Stoppers on 1800 333 000.

STATE CORONER’S COURT OF NEW SOUTH WALES

Inquest: Inquest into the disappearance and suspected death of Bennett Dominick

Hearing dates: 4 to 7 June 2019 and 22 to 23 June 2020

Date of findings: 25 June 2020

Place of findings: NSW Coroners Court, Lidcombe

Findings of: State Coroner, Magistrate Teresa O’Sullivan

These are the findings of an inquest into the disappearance and suspected death of Bennett Dominick.

Identity of deceased: The deceased person was Bennett Campbell Dominick.

Date of death: Ben died on or shortly after 10 January 2015.

Place of death: Ben died in the Coocoran Opal Fields, Lightning Ridge, NSW.

Cause and manner of death: I am unable to determine the cause or manner of Ben’s death.

Recommendations:

1. That Bennett Dominick’s disappearance be referred to the Unsolved Homicide Team of the NSW Police Force so that it can be investigated further in accordance with the protocols and procedures of the Team;

2. That the Missing Persons Registry consider amending the Missing Persons Standard Operating Procedures to make it clear that the geography surrounding Lightning Ridge is the kind of geography intended to give rise to high risk ‘red flag’; and

3. That the NSW Commissioner of Police consider that induction training for new officers at Lightning Ridge and the relevant stations in the surrounding police district specifically involve the Missing Persons Standard Operating Procedures. The training should specifically address how the nature of the geography at Lightning Ridge is likely to seriously increase the risk to a missing person’s health and/or safety, which will mean that many missing persons in the region are immediately classified as high risk.

Introduction

1. This is an inquest into the disappearance and suspected death of Bennett Dominick. Ben was a 41-year-old man who disappeared somewhere in the arid and remote opal fields outside Lightning Ridge, known as “the Coocoran”, on 10 January 2015. Ben had farewelled his partner Ashleigh Walsh and their three young children on 10 January 2015 and left their house at Lightning Ridge with his brother Tim Dominick to travel to the Coocoran opal fields and spend a couple of days at their settlement at the opal fields. He spent the day drinking with different miners at the Coocoran including Bruce Shipway and Anthi Ilpola who appear to be the last people to see Ben alive.

2. On 13 January 2015, Tim and Ashleigh reported Ben missing to police after he failed to make contact with them. Ben was an inveterate drinker and cannabis user. He also had a history of violence but there was evidence that he would not fail to make contact with his children after more than a few days.

3. Ben owned a green Ford Falcon sedan with the registration BR44VH (“Ben’s car”). On 13 January 2015, some hours after he was reported missing, Ben’s car was found parked at an electrical substation in Lightning Ridge. It is not clear when Ben’s car was driven from the Coocoran back into town. Nor is it clear who drove it. The car was found parked in third gear, the petrol tank had fuel and the seat was set for a tall person to drive. The car contained Ben’s wallet, loose money, tobacco and his mobile phone. A pouch of tobacco, a brand he didn’t smoke, was also in the car. The car windows were down, a door was unlocked, the keys were in the ignition and the radio was missing.

4. When Ben’s car was found, three days had passed since Ben was last seen. A further six days would pass before police conducted a search of the immediate area surrounding the car. I am of the view that this period of inactivity has made it far more difficult to determine what happened to Ben.

5. In the five intervening years since Ben went missing a number of ‘proof of life’ checks have been carried out, which reveal that there have been no transactions on his bank account, nor with any other authorities. Ben has not made contact with his family whom he loved dearly. The only clues to his disappearance are Ben’s car, the evidence of the last people who saw him and the people who knew him best.

6. For the reasons that follow I find that Ben died on or shortly after 10 January 2015 at Lightning Ridge. However, I am unable to make a finding as to the manner or cause of his death.

The role of the Coroner

7. The role of a Coroner, as set out in s. 81 of the Coroners Act 2009 (NSW) (“the Act”), is to make findings as to the: (a) identity of the deceased; (b) date and place of the person’s death; (c) physical or medical cause of death; and (d) manner of death, in other words, the circumstances surrounding the death.

8. Pursuant to s. 27 of the Act, an inquest is required when the manner and cause of a person’s death have not been sufficiently disclosed. In this case, neither the exact cause nor the circumstances of Ben’s death could be readily ascertained.

9. The decision about whether a person is dead is considered a “threshold question” in a missing person case. Given the seriousness of the finding, it is well established that the court should apply the Briginshaw standard. The proof of death must be clear, cogent and exact. At common law, there is a presumption in favour of the continuance of life, however it is not a rigid presumption and the circumstances of any given case must be carefully examined before a finding of death can be made.

10. In the circumstances of this case, there has also been a need to consider whether Ben’s disappearance was the result of foul play or whether it may have been intentionally self-inflicted. It is important to note that suicide can never be presumed in this jurisdiction. It is generally accepted that such a finding will not be made without cogent evidence; however, the coroner must turn his or her mind to all possibilities. Ultimately, the coroner must be satisfied to the Briginshaw standard, on the basis of clear evidence

11. In addition to the above, pursuant to s. 82 of the Act, a Coroner may make recommendations in relation to matters which have the capacity to improve public health and safety in the future, arising out of the death in question.

The proceedings

12. An inquest into Ben’s disappearance and suspected death was held at the Walgett Local Court and various locations in and around Lightning Ridge from 4 June 2019 to 7 June 2019 and at the State Coroner’s Court in Lidcombe from 22 to 23 June 2020. In preparing these findings, the Court was greatly assisted by the opportunity to visit the Coocoran outside Lightning Ridge where Ben was last reported seen.

13. Over five years have passed between Ben’s disappearance and evidence being heard in this inquest. It is clear that the memories of each witness were tested by those years but I am satisfied that all witnesses gave candid evidence and did their best to assist, notwithstanding the intervening period.

The focus of the inquest

14. Pursuant to s. 81 of the Act, the inquest examined the following issues. (1) Determination of the statutory findings required under s. 81 of the Act, including as to manner and cause of death, specifically: (a) Whether Ben is alive; or (b) Whether a homicide was committed, or whether misadventure or suicide are unable to be excluded. (2) The adequacy or otherwise of the response of the NSW Police Force (“NSWPF”) following the missing person report in relation to Ben, including: (a) The risk assessment process; (b) How the search process was documented prior to 20 January 2015; (c) The timing and use of specialist services, including a trained search and rescue operative; and (d) Compliance with aspects of the NSWPF Missing Persons Standard Operating Procedures published in 2013 and updated June 2016 (“MP SOPs”) that were in place at the time that Ben disappeared. (3) The adequacy of the training of police officers in relation to the MP SOPs in the relevant Local Area Command (“LAC”).

The facts

Personal circumstances

15. Bennett Campbell Dominick was born on 27 July 1973. He had spent a large part of his life in Lightning Ridge, which is located just off the Castlereagh Highway between Walgett and the Queensland border.

16. Ben had two brothers, Timothy Dominick (“Tim”) and Luke Dominick, as well as an adopted brother, Victor Thornton, who was known to the Dominick family as “Mark”. Ben was particularly close with Tim. They were “best mates” growing up. Ben was also very close to his mother, Carol Dominick, and his father, William “Billy” Dominick, who was diagnosed with cancer in the months preceding Ben’s disappearance. Tragically, William Dominick died without ever learning what happened to his son.

17. At the time of his disappearance in January 2015, Ben had been in a relationship with Ashleigh Walsh (“Ashleigh”) for approximately seven years. The couple lived on Rainbow Street in Lightning Ridge with Ben’s father, whom the couple were caring for, along with their three children: Billy-Jo, born in 2010; Suzanne, born in 2011; and Max, born in 2013. Ben adored his kids. He would play with them a lot, taking them journeying in old cars kept out at the Coocoran. Some of Ashleigh’s fondest memories of Ben as a dad were of him taking the kids on the quad bike. Ashleigh said Ben was a very nurturing father whose caring nature was inseparable from his wild side.

18. The family had lived at Rainbow Street for approximately six months. Previously they had lived on a camp at Tim’s mining claim at the Coocoran since 2008, essentially living off the grid (“Ben’s camp”). The Coocoran is an area located approximately 20 kilometres west of Lightning Ridge. It contains approximately 5,000 open mining shafts located around small bush-style dwellings. Leases for land holdings within the Coocoran are held by many individuals and entitle them to live, build and mine the area of their lease. In summer, the weather in the area is extreme and many people leave town during that period.

19. When living at the camp Ben’s family did not have running water or any electricity except a generator. They had only the water they carried out to the camp and set up on a tank, which Ben had set up so his family could have small comforts like a bath. Ben also ingeniously, albeit possibly dangerously, managed to construct an air-conditioning unit at his camp by redirecting cool air to the surface from the mine shafts below.

20. Between 1997 and 2001, Ben was in a relationship with Melanie White. Their son, Justin White (“Justin”), was born in 1997. Following the breakdown of the relationship with Ms White, Ben became estranged from Justin. In February 2014, Justin tragically died by suicide, aged only 16. Ben’s family told police that his father’s cancer diagnosis, as well as Justin’s suicide, had a profound effect on him.

21. Ben was dependent on a disability support pension from Centrelink, receiving approximately $580 per fortnight. He had long been dependent on alcohol and cannabis. Ashleigh had never seen him abstain from it.

22. Ben was well-known to local police and often came to their attention due to incidents of alcohol-related violence and domestic violence, for which he had spent short periods in custody.

23. Ben’s family miss him greatly. Although Ben “could get a bit wild now and then and carry on,” as Tim described, “he was a good father, a lovely man … a top bloke. He was my best mate”. He was the type of person who, when driving around town, would stop to “have a yarn”, or help out anyone who had broken down, whether he knew them or not. Saturday, 10 January 2015 Ben and Tim set out for the Coocoran

24. On 10 January 2015, Ben and his father drove to Tim’s home in Lightning Ridge, collected Tim and returned to the Rainbow Street house. Tim was suicidal because his partner had left him on New Year’s Day, taking their kids with her. Tim had called up his brother, Ben, and the two decided that they would travel to the Coocoran to do some work for a local opal mine operator, Neil Morris. Ben was known to go to the Coocoran with Tim and “wash dirt”, which refers to using a mechanical agitator to separate and sift dirt to detect opals.

25. Ben and Tim left Rainbow Street at approximately 9:30am, travelling to the Coocoran in Ben’s green Ford Falcon.

26. Ben told Ashleigh that he would see her “either Sunday afternoon or Monday morning”. Ashleigh told police that Ben took some frozen food, some beer and ice with him, as well as some food scraps for the chickens that Ben kept at the Coocoran property. The brothers also had a carton of beer each. Ben drank XXXX and Tim drank VB. There is no evidence that they carried any water with them and Ben’s friends and associates gave evidence that he wasn’t in the habit of drinking water. On 10 and 11 January 2015, the temperature at Lightning Ridge reached maximums of 36o C and 38 o C respectively. Ben and Tim arrive at the Coocoran

27. Although the Coocoran is a remote area, it is not far from Lightning Ridge. Ashleigh estimated that it takes about 15 minutes to drive from town to the Coocoran. The Coocoran can be accessed by a number of different roads. For a number of years, Coocoran Lake has been dry allowing people to drive across it to properties located west of its banks. The lake is one of possibly hundreds of different routes, many of which cut through scrub land, that are used to access the mining fields from Lightning Ridge. It is not clear on the evidence the precise route that Ben and Tim took to the Coocoran on 10 January 2015.

28. As indicated above, at the time of his disappearance, Ben’s family frequently visited Ben’s camp at the Old Coocoran opal fields where they had resided prior to moving to the house on Rainbow Street. The mining lease was owned by Tim who allowed his brother to use the area freely.

29. Ben and Tim visited a number of people when they got to the Coocoran. There are a number of inconsistencies in the evidence as to the exact order the visits took place and I have not included time estimates of the witnesses in these findings as they are all loose estimates and fundamentally irreconcilable with each other. I am satisfied that the following events occurred that day.

Shane Cridland’s camp

30. Arriving at the Coocoran, it seems that the brothers first asked local resident Shane Cridland if he would like to come out to wash dirt at the Water Tank 5 site but he had other plans. Mr Cridland thinks they visited him “fairly early” and stayed about half an hour. Mr Cridland said that the brothers were in good spirits and had a carton of beer each. “He was happy,” Mr Cridland said of Ben; “he was in a happy mood, to be working.”

Tank 5

31. Tim said that he and Ben intended to work at Tank 5, about two kilometres from Ben’s camp, for a couple of days. He also said that when they attempted to commence the work the agitator they wanted to use was broken, which was frustrating because they had paid work lined up. Ben started “getting a bit angry”.

32. Neil Schnelleger saw the brothers while they were at Tank 5, as did Terence Pocock. Mr Pocock said Ben and Tim were with Phillip and Neil Morris. Ben appeared to have a few drinks under his belt, but Mr Pocock said that he did not seem aggressive. The Dominick brothers decided to go drinking with Neil Taylor at his camp. Mr Pocock said Ben did a burnout as he drove off with Tim. A number of witnesses gave evidence that Ben liked doing donuts and burnouts in his car. Martin Leuken’s camp

33. On the way to Mr Taylor’s camp, Tim and Ben dropped by Martin Leuken’s camp and told him they were heading to see Mr Taylor.

34. Tim told police that he and Ben drove to “Martin’s first”. Mr Leuken told police that on 10 January 2015, he was visited by Tim and Ben at approximately 9:00am and that they were travelling in Ben’s Ford Falcon. Mr Leuken said that it was a social visit, that Ben was in good spirits, that they stayed for about 20 minutes, and that they told him that they were on their way to Mr Taylor’s camp. Tim gave evidence that Ben “got a bit wild there” after consuming a couple of beers, which he explained as “no big issue, it was just crap”. “Ben was in a mood,” Tim said. Neil Taylor’s camp

35. Ben then drove Tim to Mr Taylor’s mine site at the Coocoran. It is not entirely clear what time they arrived there or what happened afterward. Tim told police that after dropping him at Mr Taylor’s, Ben planned to visit his camp at the Coocoran to feed the animals he kept there. Tim said that Ben returned to Mr Taylor’s property one or two hours after having dropped him off. Tim stated that in the interim period, Ben had visited Bruce Shipway’s property.

36. Mr Taylor told police that Ben arrived separately at Mr Taylor’s mining site in his car about 20 minutes after Tim, and that the men then stayed there for the next two to three hours talking and drinking alcohol. Robert (“Two Bob”) O’Neill was also present.

37. At Mr Taylor’s camp, Ben and Tim played a prank on Mr Taylor, turning off his air hammer while he was mining below. The men drank some beers.

38. Mr Taylor stated that whilst the men were sitting around drinking, Ben began talking about his son Justin, and became agitated and upset. Ben had an argument with Tim and left in his car. Ben was known to be difficult when he was drunk and would get into arguments which sometimes escalated to violence. Tim said that this was the last time that he saw his brother. It is likely that this argument actually occurred during Ben’s second visit to Mr Taylor’s camp after he visited Mr Shipway’s property, as I outline at [44]-[45] below.

39. Whilst Ben’s movements immediately after he left Mr Taylor’s property are unclear, it is not in dispute that he left by himself in his car. Mr Taylor noticed that Ben drove away erratically and collided with a large rock; however he continued driving away from the property.

Bruce Shipway’s camp

40. Bruce Shipway resides at a mining camp at the Coocoran and, at the time of Ben’s disappearance, had known him for approximately six years. He told police that he socialised regularly with Ben, both in Lightning Ridge and at the Coocoran, and they usually saw each other a “couple of times a week”.

41. Anthi Ilpola lived at a property owned by his father at the Coocoran from approximately February 2015 until July or August 2015, when he moved to Queensland. Mr Ilpola’s property at the Coocoran was about 400 metres from that of Mr Shipway. Mr Ilpola is now deceased.

42. Mr Shipway told police that he was at his property repairing cars with Mr Ilpola when Ben arrived on a quad bike. Mr Ilpola also told police that Ben arrived at the property on a quad bike. It seems that Ben must have collected a quad bike from the camp at the Coocoran at some point that day, however the time at which this occurred is unclear.

43. Mr Shipway and Mr Ilpola told police that Ben drove the quad bike aggressively at the car they were repairing, possibly as a prank, but he collided with the car while Mr Ilpola was underneath it and just avoided injuring him. Ben asked Mr Shipway if he had any beer, and Mr Shipway gave him a cup of wine, which Ben drank, before riding the quad bike away from the property. Mr Shipway said that Ben appeared to be very angry, swearing and behaving aggressively.

Ben returns to Mr Taylor’s camp

44. It appears that at some time after the incident at Mr Shipway’s camp, Ben returned to Mr Taylor’s camp. It seems Ben returned in his car, because Tim recalled noticing that the food scraps were still in the back seat, meaning that Ben hadn’t gone to the camp to feed the chickens as planned. Tim did not recall seeing Ben’s quad bike. Ben told Tim about what had happened with Mr Shipway and Mr Ilpola, including him having hit the car with his quad bike.

45. The men kept drinking and talking with Two Bob, however after some time an argument broke out. Ben left again. According to witnesses he was slurring his words and driving erratically. At this point I should note the evidence about the events of the second visit were hard to differentiate from the events of Ben’s earlier visit. The witnesses were obviously affected by the passage of time and alcohol consumed on the day.

46. It was confirmed that, after Ben left Mr Taylor’s camp, Tim made his way back to town with Robert Matthew Ellis where Tim spent time with a group of people including Mr Ellis, Robert Smith and Hayley Barron.

Mr Pocock spots Ben driving near Molyneux’s opal field

47. At about 2:00pm, Mr Pocock saw Ben driving in his car near Molyneux’s opal field. Mr Pocock remembered Ben being alone, doing burnouts whilst holding a longneck and travelling east towards the Old Coocoran. However, Neil Schnelleger thought Ben was with Tim. Mr Pocock said the next day he saw burnouts marks that seemed to stop at the Old Coocoran and didn’t go further into town. Ben returns to Mr Shipway’s camp

48. According to Mr Shipway and Mr Ilpola, Ben returned to Mr Shipway’s camp at some point that day in his car after previously leaving on his quad bike. It is unclear what time this occurred, but it is likely to have been in the afternoon.

49. In an interview conducted on 2 December 2015, Mr Shipway told police that he had been in Ben’s car a number of times, most recently in January 2015 when he had been seated in the passenger seat. During that interview, Mr Shipway also told police that he thought he only saw Ben once on 10 January 2015, when Ben rode the quad bike to his property and collided with the car which he and Mr Ilpola were repairing. In his earlier statement to police in January 2015, however, Mr Shipway had said that after departing on the quad bike Ben returned to his property in his car approximately one to two hours later. Mr Shipway stated that Ben yelled at him, was “more off his face … than earlier”, and that he then got back in his car and left the property. He said that Ben may have asked again for beer but accepted wine.

50. In his statement to police in January 2015, Mr Ilpola told police that Ben returned to Mr Shipway’s camp that day at approximately 3:00pm and again asked them for alcohol. Mr Ilpola also said that Ben said that his car lights weren’t working, so Mr Ilpola got into the Ford Falcon to check the lights and, after he alighted from the car, Ben drove off at speed.

51. Mr Ilpola said that Ben’s eyes were like pinpricks and he thought he was on something. Both Mr Ilpola and Mr Shipway told police that Ben drove his car away from the property and that this was the last time they saw him. If correct, this appears to be the last time that Ben was seen by anyone.

52. In a further interview conducted on 19 November 2015, Mr Ilpola again told police that he had sat in Ben’s car that day to check his lights. He also told police in the interview that whilst he was checking the lights he was sitting in the driver’s seat of the car, and that Mr Shipway was sitting in the front passenger seat rolling a cigarette, which he lit using the cigarette lighter in the vehicle. Mr Ilpola said that Ben was only at the property for about 15 minutes.

Evening

53. Ashleigh told police that by 6:00pm on 10 January 2015, when she had not heard from Tim or Ben she tried to call Ben’s mobile phone about “6 or 7 times during the night”, however it diverted to message bank. She describes the mobile phone reception at the Coocoran as being good.

54. Robert Matthew Ellis told police that later on 10 January 2015, when Tim and Mr Taylor ran out of alcohol, Tim asked him for a lift back to Lightning Ridge. Mr Ellis stated that he gave Tim a lift on his quad bike to a nearby property belonging to Robert Smith, where they stayed and drank until approximately 2:00am the next morning. Mr Ellis then dropped Tim off at a mining camp at Nebea Hill at approximately 2:30am on Sunday, 11 January 2015.

Sunday, 11 January 2015

55. Ashleigh told police that early on 11 January 2015, Tim visited her at the Rainbow Street house and they discussed the fact that they had not been able to contact Ben. Ashleigh said that both she and Tim attempted to call Ben on his mobile phone several times that morning; however it again diverted to message bank. They knew “something was going on” because, as Tim described, “there’s no way he’d leave his kids and not let anyone know where he was or anything.” The unequivocal evidence given at the inquest was that Ben would sometimes have arguments with Ashleigh, but he would rarely go for any time without calling their children.

56. On 11 January 2015 Phillip and Neil Morris told Tim that they had been driving around looking for Ben because they wanted to meet him at their mining camp the next day. Tim also telephoned Mr Cridland that afternoon and they agreed to meet the next day to look for Ben.

57. At approximately 1:30pm on 11 January 2015, Ashleigh organised for a friend to drive her out to Ben’s camp at the Coocoran so she could look for Ben. When Ashleigh arrived at the camp she observed that it did not seem like Ben had been there in the last few days, as there were no track marks from any cars and the dirt at the front of the camp was undisturbed. She also noticed that the quad bike was parked in its normal position but she could not see any tracks indicating that it had been used. When Ashleigh returned to Lightning Ridge later that afternoon she continued attempting to reach Ben on his mobile phone without success.

Monday, 12 January 2015 Ben’s car is reportedly seen by Jeremy Lohse

58. At approximately 5:30am on 12 January 2015, Jeremy Lohse was standing outside the front of his residence on Opal Street, Lightning Ridge, when he noticed what he believed to be Ben’s Ford Falcon drive past his house. He told police that the car was travelling towards the town centre of Lightning Ridge.

59. Mr Lohse’s house is around the corner from Ben’s home in Lightning Ridge, however it is on the other side of town from the most direct way from the Coocoran fields to the substation.

60. Mr Lohse told police that he often saw Ben drive past his house in the mornings, and that Ben would usually either wave or stop to speak to Mr Lohse. Mr Lohse stated that on this occasion he could not see who was driving the vehicle because the windows were wound up, and the car did not stop or acknowledge him in any way.

Ben’s friends and family meet at the Caltex to search for him

61. At some stage on 12 January 2015, Tim, Mr Cridland, Ashleigh and a female friend of Ashleigh, Melissa Adamson, met at the Caltex Service Station on Onyx Street and discussed searching for Ben. Mr Cridland states that this meeting occurred at 8:30am or 9:00am and that he and Tim then left the service station in his vehicle and drove out of town to the Coocoran to look for Ben.

62. Inspector Linda Bradbury (“Inspector Bradbury”) stated that she completed her shift at Lightning Ridge Police Station earlier than normal on 12 January 2015, at approximately 2:00pm. At about 3:00pm that afternoon, she states that she saw Tim and Ben standing at the Caltex service station on Onyx Street. She also saw Ashleigh leaning into the window of a vehicle parked nearby on Morilla Street, talking to a woman in the vehicle. Inspector Bradbury recognised the car as belonging to a suspected drug dealer so she telephoned the police station and relayed the information to an officer.

63. Ben’s friends and family searched for him until approximately 2:00pm that day but did not find him, his car or any of his belongings. Mr Cridland said they saw a lot of burnout or spin marks on the road at Molyneux’s opal field about 500 meters north of the grid. They searched Ben’s camp, including one of the underground mining shafts. They then went to Tank 5, where they “went down to the agitator and had a look” and then they “drove around the general fields, which [are] fairly extensive out there and generally asked if [the residents had] seen him.” Mr Cridland explained that they spoke to Grant Warhurst and Martin Leuken, neither of whom had seen Ben nor had any suggestions about where they might look. “[T]hey were as much confused as we were,” Mr Cridland said.

64. While at Ben’s camp, Ashleigh did not see any sign that Ben had been there or stayed there in the intervening period. Nor did she see any moved dirt or car tyres. She gave evidence that she became really worried when she saw a small blue Esky at the camp because Ben would carry that with him everywhere he went, with cannabis and a bong inside. Ben was dependent on cannabis and would apparently not visit his camp without taking his “bong esky” with him. Activities of Mr Shipway and Mr Ilpola

65. During his police interview in December 2015, Mr Shipway confirmed that on 12 January 2015 he had been in Lightning Ridge with Mr Ilpola. He said they were organising the repair and registration of a motor vehicle. Mr Shipway told police that Mr Ilpola drove that vehicle from the Coocoran to Lightning Ridge on that day, notwithstanding the fact that Mr Ilpola was an unlicensed driver at the time.

Tuesday, 13 January 2015 Ben is reported missing to police

66. At about 1:00pm on 13 January 2015, Ashleigh and Tim reported Ben missing at Lightning Ridge Police Station. They spoke to Constable Troy Cridland and Inspector Bradbury. They told the police they had not seen Ben since about 2:00pm on 10 January 2015 and they were concerned about him. By this time, approximately 71 hours had passed since Ben was last seen by Mr Shipway and Mr Ilpola.

67. Constable Cridland created a comprehensive record of Ashleigh and Tim’s report. Constable Cridland’s evidence was that Tim seemed “upset”, his hands were shaking and that Tim’s demeanour was different from how he usually presented. He also stated that Ashleigh said she “was really worried about [Ben]”. I also note that Tim and Ashleigh apparently told Constable Cridland that they had spoken to the person from whom Ben ordinarily bought cannabis on a daily basis and Ben had not been at that location since Saturday 10 January 2015 which was “out of the ordinary”.

68. However, Inspector Bradbury had doubts about the validity of the report because she believed that she had seen Ben the previous day at the Caltex with Tim and Ashleigh. She thought that Ben and Ashleigh had been talking to a local drug dealer and therefore that Tim and Ashleigh either weren’t telling the truth or had their dates mixed up. She said that “Tim appeared reluctant and frustrated in providing information to police”.

69. Inspector Bradbury stated that she immediately “took [Ashleigh] aside and told her I had seen her with Ben at the Caltex service station the day before”. Ashleigh attempted to correct Inspector Bradbury’s misapprehension and told her that she had been with another male who looked like Ben. Ashleigh admitted speaking to a drug dealer, but only because she was trying to find Ben, who was dependent on cannabis. Inspector Bradbury’s purported sighting is described in a COPS entry as being a “contradiction” in Ashleigh’s account of Ben being missing. In their oral evidence, Ashleigh and Mr Cridland each said they did not recall seeing Inspector Bradbury at the Caltex. Ashleigh said that Tim looks more like Ben than Mr Cridland does.

70. I note here that Inspector Bradbury’s firm belief that she saw Ben at the Caltex (despite Ashleigh’s assurance otherwise) adversely affected Inspector Bradbury’s opinion about the veracity of Ashleigh and Tim’s missing person report from the outset and resulted in police treating Ashleigh’s report of Ben being missing with unwarranted scepticism. Inspector Bradbury’s certainty that she had seen Ben at the Caltex on 12 January 2015 also appears to have led to a delay in police obtaining evidence to confirm or exclude her belief. Lightning Ridge police did not make any enquiries with the proprietors of the Caltex and other nearby premises to obtain downloads or copies of any CCTV until 20 January 2015, some seven days after Ben had been reported missing, and eight days after the supposed sighting. Inspector Bradbury states that she made inquiries on 14 January 2015 and no relevant footage existed, but there is no record of those inquiries and it does not appear to have been conveyed to any other officer. On 5 February 2015, police were advised that the available CCTV footage from the Caltex did not extend as far back at 12 January 2015.

71. When Ben was reported missing to Constable Cridland, a written risk assessment was not completed. Inspector Bradbury was the supervising officer at the time that the report was made but she did not instruct Constable Cridland to complete a written risk assessment. Senior Constable Morgan Ramsay (“SC Ramsay”) assumed supervisory responsibilities at Lightning Ridge Police Station that afternoon, receiving a handover from Inspector Bradbury which included information about the missing person report of Tim and Ashleigh. The COPS Event created by Constable Cridland in relation to the Ben’s disappearance was reviewed by SC Ramsay and “resubmitted” by him for “further attention” because the initial version of the report read as if “Mr Dominick had been located and he had not”. However SC Ramsay did not require that a risk assessment be documented.

Police conduct patrols in search of Ben

72. At approximately 6:00pm on 13 January 2015, police conducted vehicle patrols of 9 Mile Road, Wyoming and Coocoran mining access roads in search of Ben. Police had apparently been advised that this was the route that Ben ordinarily travelled when driving to/from Lightning Ridge. There is no physical record of the areas searched. Police also spoke with local landowner Maryanne Spooner who stated that she believed she saw Ben from a distance at 6:50am that morning. It later became apparent that this sighting was unlikely to have been Ben.

Ben’s Ford Falcon is found

73. At approximately 7:00pm on 13 January 2015, Ben’s Ford Falcon was found parked at the substation on Onyx Street. It was about 30 kilometres from where Ben was last seen and 300 metres from the town’s main pub, the Outback Resort. Ben was banned from the pub and it is likely he would have been immediately noticed if he had tried to enter.

74. Robert Jelbart, who found Ben’s car, told police that he was walking his dog at the sports fields on Onyx Street when he noticed a green sedan parked in the substation across the road. He “caught a glimpse of it through the levy bank that surrounds the substation” and it was “pretty hard to see” from the roadway. He noticed that he was leaving footprints in the black soil and there were no other footprints or tyre marks near the car. This made him think the car had been abandoned for some days because it had not recently rained. He contacted the police and a short time later, SC Ramsay and Constable Abanoub Gouhar attended the substation and Mr Jelbart escorted them to the car.

75. SC Ramsay recognised the car as Ben’s Ford Falcon. He noticed that the keys were in the ignition and that a foul smell was emanating from within the vehicle. SC Ramsay opened the boot of Ben’s car and observed that it contained a number of 20L fuel cans. Records indicate that the police obtained information from Mr Jelbart before securing the vehicle, seizing the keys and the mobile phone, and leaving the location.

76. SC Ramsay believed that the car may have been parked at the substation, nearby the Outback Hotel and mining access roads, because it was unregistered. However the officer in charge of the coronial investigation, Detective Senior Constable Tilly Shrubsole (“DSC Shrubsole”), confirmed in evidence that Ben had his license and the car was registered at the time. Further, Ben was not in the habit of avoiding police when driving, even if he had been consuming alcohol.

77. Ben had been reported missing earlier that day. A number of factors ought to have been regarded as significant at the time by attending police. The car’s driver’s side window was fully down and the back window on the driver’s side was halfway down. A door was unlocked. The key was in the ignition. The radio was missing. Ben’s phone was in the centre console. His hunting knife, which he was known to carry with him everywhere, was also in the car. The food that Ben had packed to take to the camp was untouched and apparently rotting. Lastly, there was money and pouches of White Ox tobacco on the floor.

78. On any view, the discovery of the car was a reason for significant concern as to Ben’s whereabouts on and from the evening of 13 January 2015, particularly given that by that time, he had been missing in extreme weather conditions for approximately 72 hours.

When, and by whom, was Ben’s car driven back into town?

79. A primary issue in this inquest is when and by whom Ben’s car was driven back into town. A secondary issue is the police’s response to finding the car, in particular because Ben had been reported missing. The discovery of the car means that either: (1) Ben did not have an accident, meet foul play or die by suicide at the opal fields; or (2) If he did, someone drove his car back to town and left it at the substation.

80. If Ben drove the car to the substation it raises the questions as to where he was going, why he left his valuables behind and where he went next? The latter possibility raises the question of why a person would want to remove the car from where it was located? Anthony Leeder (known as “Frog”) thinks he saw Ben’s car parked at the substation on Sunday morning, 11 January 2015, although in his evidence he was not sure of the day. At the time, Frog was working in his capacity as Team Leader for the Walgett Shire Council at the main pump station for Lightning Ridge, checking the bore head. He did this daily, meaning that if he saw Ben’s car on a Sunday, this would not stand out from his routine. Frog says he saw Ben’s car a couple of times after that and then “the police impounded it”.

81. The reliability of Frog’s evidence is weakened by the passage of 18 months between him seeing the car and police taking a statement from him.

82. Frog gave evidence at the hearing to the effect that he only inspected the Ford Falcon after police were alerted to it on 13 January 2015. Police had asked him to open up nearby effluent ponds to look for Ben. When he inspected the car there was no crime scene tape or anything that suggested that the vehicle had been secured by police. Frog is “pretty sure” that the key remained in the ignition and that the driver’s side window was still down and that food items remained in the backseat. Counsel for the Commissioner of Police, Mr Coffey, suggested to Frog that he was mistaken about the unsecured state of the car, but Frog was adamant: “that window was definitely down in that car. I can remember it clear as day”.

83. Mr Cridland told police in May 2016 that when he and Tim drove to the Coocoran from the Caltex Service Station on 12 January 2015 they drove down Onyx Street, past the substation where Ben’s car had been located. Mr Cridland said that if the car had been parked at the substation when they drove past on their way out of town, “Tim or I would have seen it”. However, the fact that Ben’s car was not easily visible from the roadway reduces the significance of this evidence.

84. DSC Shrubsole’s opinion is that someone other than Ben left the car at the substation. One reason I place great weight on her evidence is because of the value of her local knowledge. DSC Shrubsole cannot understand how somebody as well known in Lightning Ridge as Ben could have driven into town undetected. DSC Shrubsole had also never seen any car parked at this location, let alone Ben’s car. She gave evidence that someone could have driven Ben’s car to the substation without being seen by driving on one of the many tracks through the scrubland from the Coocoran and into town. DSC Shrubsole stated that if someone was travelling from the Coocoran, the substation would have been the closest spot to town where they could conceal a car and comfortably walk to town. However, DSC Shrubsole accepts that one issue with this hypothesis is that Jeremy Lohse’s sighting of Ben’s car would place the car on the other side of Lightning Ridge. DSC Shrubsole places some weight on Mr Lohse’s evidence because he emphasised how unusual it was for the car to have its windows up and for Ben not to stop to chat.

85. For these reasons, I have concluded on the available evidence that Ben did not drive his car back to town. Regrettably, there is insufficient evidence to say who drove the car, the route they took or why they chose to do so. The police investigation Wednesday, 14 January 2015

86. On 14 January 2015, Ben was due to attend his court required community service which he would reportedly never miss. When Ben failed to attend, his Community Corrections case manager, Pamela Robinson attended Lightning Ridge Police Station at approximately 11:30am to make an enquiry as to his whereabouts. A number of police patrols were apparently undertaken in the days following 13 January 2015 when Ben was reported missing and the Ford Falcon was located; however there is scant evidence that outlines the specific steps that were taken by police in the days following the missing person report.

87. An example of this is Inspector Bradbury’s recording of a COPS entry at 8:16am on 14 January 2015, that she had tasked the car crew to attend Lightning Ridge resort to enquire if Ben had been sighted there and, if so, to view CCTV footage at the pub. Inspector Bradbury later asserted in her second statement dated 18 January 2015 that she carried out that task, and a further task of viewing the CCTV footage at the Caltex service station, herself. She states that she reviewed the CCTV footage at the Caltex, but that the area in which she believed she saw Ben was not in the recording frame. She stated that she “did not take a copy of this footage as it provided no assistance”. I note here that Inspector Bradbury did not appear to record these inquiries or communicate them to the officer then in charge of the investigation, Detective Senior Constable Stephen Innes (“DSC Innes”). On 17 January 2015 DSC Innes noted that CCTV could confirm whether or not Ben was present at the Caltex on 12 January 2015, and on 20 January 2015 DSC Innes tasked Detective Senior Constables Samantha Neader and Christopher Wallis to attend the Caltex and determine whether Ben was depicted on the CCTV footage. Again, later on 5 February 2015, Detective Sergeant Scott Baker requested the CCTV footage at the Caltex and was informed that the CCTV footage for 12 January 2015 had been overwritten.

Thursday, 15 January 2015

The police response to the discovery of the Ford Falcon

88. At approximately 9:00am on 15 January 2015, Inspector Bradbury and Scene of Crime Officer Tanya Bobako (“SOCO Bobako”) attended the substation where the Ford Falcon remained parked, unsecured. SOCO Bobako had not been briefed on the missing person investigation. She was simply told to attend the substation in relation to a vehicle of interest from which she was to “seize exhibits and so forth”. Inspector Bradbury and SOCO Bobako drove out to the substation together. On the way, SOCO Bobako recalls being told by Inspector Bradbury that she had been “asked to return the vehicle to the station or actually drive the vehicle to the station, so she asked me to convey her out there to pick the vehicle up”.

89. SOCO Bobako did not understand her role to be that of crime officer. Rather, she “was just purely to convey the officer [Inspector Bradbury] out there to pick the car up and return it to the station”. Had she been advised she was acting as a crime scene officer at the time, SOCO Bobako says she “would’ve contacted my senior officers and got instruction [sic] about that”.

90. Upon approaching the substation, SOCO Bobako noted that “[t]he vehicle couldn’t be seen from the roadway. I couldn’t see it immediately, until I went into the power station”. Approaching Ben’s car she noticed flies and a “quite distinctive” smell. Contrary to Frog’s evidence (at [82] above), SOCO Bobako’s clear recollection was that the car’s windows were up. She described the car as “cluttered”. Inspector Bradbury first opened the boot with the key, wearing protective equipment while doing so. Despite the fact that she was not in attendance in her usual capacity, SOCO Bobako said that she was conscious that both her and Inspector Bradbury be protected from any contamination, injury or infection; but also, so that any evidence that may become an exhibit was also preserved. SOCO Bobako was concerned that there was the possibility of human remains being located in the vehicle.

91. Inspector Bradbury inspected the boot finding only personal items and a first-aid kit. She then opened the back door and located a number of personal items, including a hunting knife, a small amount of cash, empty beer cans, packets of White Ox tobacco, the food that Ashleigh had packed, and the food scraps for the animals at Ben’s camp. SOCO Bobako attributes the source of the smell to these rotting food items. Inspector Bradbury said in a statement that when she discovered these items, particularly the money, she was worried because she did not believe that Ben would leave money and tobacco in the car.

92. SOCO Bobako did not notice any footprints or tyre marks around the vehicle but she concedes she was not looking for them. Inspector Bradbury took several photographs on her phone of the car in situ. Although SOCO Bobako accepted that with hindsight she should also have taken photographs of the car in situ herself, there can be no criticism of her actions on 15 January 2015 given that her role and her knowledge of the broader investigation were so limited. Similarly, there can be no criticism of the fact that SOCO Bobako did not individually seize and package items in the car that might have been vulnerable to contamination. As she explained, the car needed to be examined by a forensic investigator who would normally be dispatched from Dubbo Crime Scene. In her view, “it was best to leave the car in situ at [that] stage”.

93. However, Ben’s car was not left in situ. Still wearing protective clothing, Inspector Bradbury drove it from the substation to Lightning Ridge Police Station. In fact in doing so she said she was going against her superior officer’s advice to return Ben’s vehicle to his family.

94. Inspector Bradbury states that prior to attending the substation she spoke with Chief Inspector Anthony Mureau (“CI Mureau”) who at that time was the Crime Manager for the Castlereagh LAC. She states she told him that she was concerned that Ben’s disappearance was suspicious and that the car may be a crime scene. She says that CI Mureau directed her not to seize Ben’s car as an exhibit because “we would be unable to obtain a tow truck for the vehicle and to return the vehicle to Tim Dominic [sic]”.

95. In a supplementary statement dated 5 December 2019, CI Mureau states that he has a “vague recollection” of Ben’s car being found in the circumstances detailed in Inspector Bradbury’s SITREP dated 14 January 2015. He doubts, however, that he would have given Inspector Bradbury a direction not to seize the car as an exhibit “when there was simply no need to given the fact that we were actually seizing the vehicle and driving it back to the station”. He recalls – again “vaguely” – making the decision “to have a police officer drive the vehicle back to the station … and secured”.

96. CI Mureau states that he made an “operational and financial decision based upon the circumstances that existed at that point in time” not to call a tow truck from Coonamble (there apparently being no local operator in Walgett or Lightning Ridge). Those circumstances were, in CI Mureau’s estimation, that police were “dealing with a missing person report less than 24hrs old, involving an adult male [sic]” and there was “nothing to suggest anything suspicious”. For the same reasons, CI Mureau did not consider deploying a forensic investigator to the scene on 15 January 2015.

97. However, contrary to CI Mureau’s evidence, by the time Inspector Bradbury and SOCO Bobako attended the substation at 9:00am on 15 January 2015, the missing person report had been on foot for nearly 48 hours, having been made at 1:00pm on 13 January 2015. Police were also aware that by that time Ben had not been seen or contacted by his friends or family for approximately five days.

98. In his supplementary statement, CI Mureau states that he does not recall any conversation with Inspector Bradbury on 15 January 2015 (which he again misidentifies as being “only one day after the missing person report was made”), to the effect that “the circumstances of the disappearance were at that time suspicious”. He relies on Inspector Bradbury’s SITREP dated 14 January 2015 for this suggestion, stating that Ben had been seen by Inspector Bradbury on 12 January 2015 at the Caltex. However, as noted above, by 15 January 2015 Inspector Bradbury’s view had apparently changed and she was concerned that Ben’s disappearance “was suspicious and that the car may be a crime scene”. This was either not conveyed to CI Mureau or not understood by him in the way that Inspector Bradbury intended. I find it unnecessary to resolve this issue in light of a series of concessions made by the NSW Police Commissioner which I outline below.

99. At 5:29pm on 15 January 2015, Inspector Bradbury issued a NEMESIS message alerting all NSW Police state-wide to Ben’s disappearance.

Subsequent investigations by police Mid to late January 2015

100. As already indicated, the specific steps that police took on all of the subsequent days are not all clearly documented. However, I am satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the following events occurred.

101. On 16 January 2015, DSC Innes recorded in his Duty Book that Ashleigh accompanied him and SOCO Bobako to the camp at Old Coocoran, at which they conducted a video walk through and took photographs of the camp. DSC Innes also noted that there had been no forensic examination of Ben’s vehicle and no ground search done.

102. On 17 January 2015, DSC Innes formulated an 18-point plan in relation to the missing person investigation within COPS narrative E57470369. CI Mureau concedes in his supplementary statement that he “cannot say with absolute certainty” that he was aware of this investigation plan, although he says he “did know at least some part” of the plan because “it was most likely discussed at some point” or he “just as likely read the narrative”. He says he cannot be certain because “the investigation was in its infancy and focussed on locating a missing person” (emphasis added). However these factors would appear to be key reasons why a supervising police officer would make himself or herself aware of an investigation plan prepared by one of his or her officers. It was also the case that four days had passed since Ben was reported missing and seven days had passed since he was last reliably seen. It is concerning that, even with the benefit of hindsight, CI Mureau was of the view that the investigation was “in its infancy” given the period of time that had elapsed since Ben had last been sighted.

103. By 17 January 2015, Ben had been missing in summer in a harsh climate for almost a week. If he had suffered misadventure, such as falling into a disused mineshaft or being injured in the opal fields, his prospects of survival were likely extinguished. Alternatively, if he had met with foul play, the evidence from the car and surrounding areas was potentially being compromised. The area surrounding Ben’s car was regrettably not searched for some days afterwards, with the first documented search of the surrounding area by an officer from Dubbo Crime Scene occurring on 19 January 2015, six days after Ben had been reported missing and his car was located.

104. On 20 January 2015, CI Mureau created Strike Force Berong (“SF Berong”) into Ben’s disappearance. The same day, Detective Sergeant Stephen Hunt (“DS Hunt”) of the Homicide Squad, State Crime Command (“SCC”), was notified that an investigation had commenced. He called DSC Innes who informed him, as DS Hunt’s notes record, “Missing Person now possibly murdered”.

105. It is unclear what, by this stage, prompted police to consider that Ben had been murdered, or whether they had identified any persons of interest. However it is of note that Mr Ilpola and Mr Shipway both provided initial statements to police on 20 January 2015 in which they both stated that they last saw Ben on Saturday 10 January 2015.

106. The available material suggests that when Senior Constable Mark Fitzpatrick (“SC Fitzpatrick”), a trained search and rescue operative, was joined to the investigation on 19 January 2015, the search for Ben commenced in a more systematic fashion. SC Fitzpatrick’s statement sets out the searches that were undertaken on 21 and 22 January 2015, and on 2, 3, 5 and 10 February 2015, along with maps showing the areas that were searched. On 21 January 2015 a command post was set up and line search was conducted, assisted by the NSW State Emergency Service (“SES”), of the area near where Ben’s Ford Falcon had been located.

107. DSC Innes was on leave from 22–26 January 2015, during which time DSC Neader and DSC Wallis were placed in charge of the investigation.

108. On 23 January 2015, a physical search of the area where Ben’s car had been located was again conducted by police. That same day, CI Mureau spoke with DS Hunt. CI Mureau cannot recall the details of that conversation, and his handwritten notes are limited to just four names (“Smith”, “Gleeson”, Ashleigh and Tim Dominick) and two phrases (“Electronic footprints” and “Phone + bank records”). It is clear, however, that CI Mureau made no request for the active assistance of the Homicide Squad at that time. This is despite the fact that he first considered the possibility of foul play “in the days immediately prior to the 23rd of January 2015 as contact was made on this date with the Homicide Squad”.

109. DS Hunt’s notes of his conversation with DSC Innes on 23 January 2015 record that he was advised that a “land and earth search [was] undertaken to 2km from where vehicle recovered – with beer cans located and a shirt on the fence” which “ceased due to danger”. He referred to there still being “no activity on bank accounts”.

110. DS Hunt’s follow up email to DSC Innes and CI Mureau, sent that afternoon, offers the following insight into the state of the investigation as at 23 January 2015. The subject line is “Re: Notification update for Missing Person/believed murdered Bennett DOMINIC [sic]” (emphasis added). DS Hunt noted that a land search had been “completed to a radius of approx. 2km from where MP vehicle located” but that it was “abandoned due to safety factors”. The assistance of PolAir was apparently sought to continue the search given that the relevant “safety factors” seem to have been “the continued risk ongoing searches created due to the terrain, open mine shafts and extreme temperatures”.

111. DS Hunt’s email also referred to an “underlying possibility” that Tim was having an affair with Ashleigh, noting that “Tim recently separated from his wife”, which was referred to a number of times in the correspondence between DSC Innes, CI Mureau and DS Hunt. The fact of this separation, along with information provided on 21 January 2015 by Tim’s adopted brother, Victor Thornton that Ben and Tim “went into the bush and only Tim came out”, seems to have founded an investigative theory that Tim and Ashleigh may be persons of interest in Ben’s disappearance. The basis for any suspicion against Tim and Ashleigh was slim to say the least. Tim and his then partner had had an unstable relationship for some time and there was no basis to think he was having an affair with Ashleigh. Mr Thornton had no knowledge of Ben’s disappearance or any information which would incriminate Tim, as he made clear in his statement to police.

112. It was not until 27 January 2015 that DSC Innes requested the assistance of the SCC. The pro forma document that DSC Innes completed described the type of offence/incident as: “Suspicious disappearance of Bennett Dominick”. DSC Innes ticked boxes indicating that the matter required investigative expertise available only within the SCC. The request was endorsed by the Castlereagh Local Area Commander, J Stewart, in the following terms: “Extremely limited resources to conduct this level of investigation. Request for Homicide Squad assistance is supported”. The request was accompanied by a comprehensive four-page investigation plan authored by DSC Innes, also dated 27 January 2015.

113. On 29 January 2015, Detective Sergeant Baker and Detective Senior Constable Tom Magann from Dubbo Crime Scene attended Lightning Ridge Police Station. At the request of detectives, SOCO Bobako seized a number of items from Ben’s car, which remained parked at the station. February 2015

114. On 3 February 2015, land searches were undertaken in the bushland west of Lightning Ridge, including near Ben’s camp and Tank 5. Lake Coocoran was searched using trail bikes and a large number of SES volunteers. A line search was also undertaken that day and mine shafts were inspected. Further searches continued with the involvement of police divers. Unfortunately, these more systematic steps yielded no results. Given the stage at which they were undertaken, these searches could realistically only have been directed at locating and recovering Ben’s body. It is unclear why they were not performed in the immediate period after Ben was reported missing, or at least upon police forming the view, around 23 January 2015, that his disappearance was suspicious.

115. On 4 February 2015, CI Mureau submitted a request for assistance to PolAir which was assessed and declined.

116. On 5 February 2015, following a request made by SC Fitzpatrick to Western Region Police Command, Police Rescue personnel with specialist equipment assisted with a search of mine shafts. Additionally, land searches were undertaken in the bushland west of Lightning Ridge and Lake Coocoran using trail bikes. A line search was also undertaken that day.

117. A further co-ordinated search occurred on 10 February 2015, which included assistance from the SES, Rural Fire Service and PolAir. The search encompassed the area where Ben’s car was located. Nothing of interest was located during that search. It is of note that police are not able to clearly identify the precise search area that was covered on that date, as only one GPS unit was available.

118. On 15 and 17 February 2015, police conducted searches of Ben’s camp and surrounding areas at the Coocoran.

119. On 20 June 2015, following the confirmation of DNA testing on 5 June 2015, namely that Mr Shipway’s DNA matched a sample taken from a White Ox tobacco packet located in Ben’s car, DS Hunt emailed DSC Shrubsole, stating: “So it seems Mr SHIPWAY and ILPOLA are firm targets … The DNA in the car is obviously interesting”. He made some suggestions to DSC Shrubsole about obtaining further evidence in relation to the tobacco.

Findings

What happened to Bennett Dominick? Is Ben deceased?

120. I am satisfied to the requisite standard that Ben is deceased. However, the evidence does not enable me to make a finding as to the cause or the manner of his death.

121. Evidence obtained by investigating police confirms that the conditions in January 2015 in Lightning Ridge were typically hot and unforgiving. Ben had no known way to survive without assistance, as he had no knife or way of obtaining food or water. There have been no signs that Ben is alive since he was last seen on 10 January 2015. He has made no Medicare or Centrelink claims, nor used his debit card. CCR records confirm that Ben did not use his mobile phone or answer it after 9 January 2015. No evidence has been obtained to suggest that he had a second handset or phone number. The usual proof of life checks, including those of electoral rolls and police databases in every state and territory have also been conducted, but returned no positive results.

122. Critically, Ben has not made contact with friends or his children. Previously, the longest amount of time that Ben had gone without contacting Ashleigh was “[a] day and a night”. Ashleigh gave candid evidence at inquest to the effect that even if the couple weren’t getting along, he would still contact their children.

Did Ben meet with foul play?

123. Whether Ben was intentionally killed by a person or persons known or unknown is not a finding I am able to make on the available evidence. Mr Shipway and Mr Ilpola

124. Some police attention has been directed to Mr Shipway and Mr Ilpola given that they were the last known people to see Ben alive on 10 January 2015.

125. Police first spoke to Mr Shipway and Mr Ilpola on 20 January 2015. This occurred by coincidence while police were making inquiries about the CCTV at the Caltex station. DSC Neader thought that Mr Shipway looked like Ben and asked about him. Both men told police that Ben had come to the camp twice on Saturday 10 January 2015 and that on both occasions he was angry and shouting.

126. In his first statement, Mr Ilpola said that when Ben came back the second time he asked Mr Ilpola to look at his car lights, which he thought it was odd as it was daytime and the lights were working. In a later interview, Mr Ilpola said he sat in the driver’s seat and Mr Shipway sat in the passenger seat and rolled and lit a cigarette with the car cigarette lighter. This does provide an explanation for the fact that Mr Shipway’s DNA matched a sample taken from a White Ox tobacco packet located in Ben’s car, however in his first statement Mr Shipway did not mention the car lights or having rolled and smoked a cigarette in Ben’s car. He said Ben had come back a second time very briefly, “more off his face” than earlier, and that Ben yelled at him about ringing Ashleigh and then drove off.

127. In a later interview, Mr Shipway told police that he had been in Ben’s car a number of times, most recently in January 2015, when he was in the passenger seat. Mr Shipway also told police that he used White Ox tobacco.

128. Mr Ilpola and Mr Shipway were in the township of Lightning Ridge on 12 January 2015 having Mr Ilpola’s Toyota Camry repaired for registration. Mr Shipway told police that Mr Ilpola drove the Camry into town that day; however it was not in dispute that Mr Shipway had a driver’s licence and Mr Ilpola did not, which was why the relevant registration forms were in Mr Shipway’s name. Conversely, Mr Ilpola told police that Mr Shipway drove the Camry into town that day. Mechanic Matthew Power told police that the Camry failed an inspection for registration on 12 January 2015; however it was returned on 14 January 2015 for repairs and on 15 January 2015 the vehicle passed the registration inspection.

129. A crime scene warrant was obtained to inspect Mr Shipway’s camp on 7 May 2015. Forensic examination did not detect any traces of blood or bodily fluid. Tim and Ashleigh

130. As discussed above, it appears that by late January 2015 police had developed an investigative theory that Tim and Ashleigh may have been having an affair and consequently have had some involvement in Ben’s disappearance.

131. This theory was not supported by any evidence, other than unrelated information provided by Mr Thornton on 21 January 2015. However, it nevertheless appears to have been the basis for serious consideration of a number of investigative techniques directed at Tim and Ashleigh. While I accept that police should keep an open mind about the potential involvement of family and spouses in a missing person case, it is difficult to reconcile the fact that Ashleigh and Tim became the apparent focus of police investigation into Ben’s disappearance. They had reported Ben’s disappearance to the police at a time when it was unlikely that anyone else would have done so, or at least done so for a considerable period. They had searched the area and quizzed his friends and associates. They told police of their grave concerns for Ben’s safety. Rudimentary investigations could have confirmed that Tim was in continuous company while he was at the Coocoran (in other words that he had an alibi) and that Ashleigh was with her children. I have seen no evidence which would direct any suspicion at Ashleigh and Tim for Ben’s disappearance and abundant evidence of their love and concern for Ben.

Did Ben die by suicide?

132. The line between alcoholism at an advanced stage and suicide can, tragically, too often be thin. The evidence has the potential to suggest that Ben’s psychological state was in decline prior to his death, possibly in combination with his heavy drinking and cannabis abuse. In the months before Ben disappeared, his father was diagnosed with cancer. This diagnosis and his son Justin’s suicide in 2014 greatly upset Ben.

133. At the time of Ben’s disappearance, Ashleigh told Inspector Bradbury that her relationship with Ben had been “good recently” but he had been depressed and consuming lots of alcohol. On 15 January 2015, Bruce and Gregg Dunn told Inspector Bradbury that Ben had made threats to harm himself. Later that day Billy Dominick told Inspector Bradbury that Ben had threatened “jumping down a mine hole and hanging himself”.

134. Accordingly, suicide cannot be excluded as a possibility. However there was a deal of evidence before me from people who knew Ben best to the effect that Ben would not have taken his own life. Mr Cridland, for example, stated, “He had a young family, which he really loved, and his children and his missus, so I don’t think he’d self-harm or anything like that, it’d be very out of character”. Tim and Ashleigh also gave evidence that they do not believe Ben would have taken his own life and that he was strongly against suicide because of Justin’s death.

135. No note or message was located and there is no evidence of Ben making any previous attempt to take his own life. Ben did not have life insurance. The apparent involvement of a third party in abandoning Ben’s car also points away from deliberate self-harm. For all these reasons I cannot exclude the possibility of suicide but I am not satisfied that Ben did die by suicide.

Did Ben die by misadventure?

136. There has been no physical evidence that enables me to make a finding that Ben died by misadventure. In fact, the discovery of Ben’s car in town and his quad bike at his camp, both fairly undamaged, appears to militate against this likelihood.

137. Nevertheless, the area in which Ben disappeared is a unique but treacherous one. There are many ways in which Ben could have died undetected in Lightning Ridge, particularly if he had been drinking. The region is dotted with countless uncovered shafts and if Ben did fall, he would have perished quickly in unforgiving conditions. Further, I cannot state with certainty that all of the uncovered shafts in the vicinity of Ben’s car have been examined. For these reasons, I consider that the particular geography of Lightning Ridge means that misadventure cannot be excluded as a possibility.

Referral to the Unsolved Homicide Team

138. The available evidence does not allow for any finding to be made as to the cause and manner of Ben’s death. Whether Ben’s death was the result of homicide or misadventure, and to a much lesser extent suicide, cannot be excluded. However, I have serious suspicion that Ben was subject to foul play. I therefore recommend that Ben’s death be referred to the Unsolved Homicide Team of the NSWPF. I propose to give a transcript of the evidence to the Unsolved Homicide Team so that Ben’s matter can be investigated further in accordance with the protocols and procedures of the Team. I hope that this referral may ensure that Ben’s case gains more continuous investigative prominence.

The police investigation into Ben’s disappearance and suspected death

139. I received a great deal of additional evidence about the investigation into Ben’s disappearance after hearing the first tranche of evidence in Walgett and Lightning Ridge on 4 to 7 June 2019. I was particularly assisted by a statement from Detective Inspector Glen Browne (“DI Browne”) of the Missing Persons Registry (“MPR”), SCC, who provided me with an overview of the revised MP SOPs published on 1 January 2020 (“2020 MP SOPs”), the differences between the 2020 MP SOPs and those in force at the time of Ben’s disappearance, and an analysis of how the 2020 MP SOPs would apply to the police response to the missing person report made in relation to Ben. DI Browne also gave evidence during the second tranche of the hearing and I found him to be an impressive and knowledgeable witness.

140. After assessing all the evidence in the case, the Commissioner of Police instructed his representatives just prior to the second tranche of hearing to make a series of concessions about deficiencies in the conduct of the missing person investigation. I will note these concessions throughout my findings but state here that they related to: (a) The way in which the investigation was conducted and managed in the critical period of days after Ben was reported missing on 13 January 2015; (b) The priority accorded to the investigation in light of the likely risk faced by Ben, particularly after his car was discovered; (c) The extent to which investigating police adhered to the procedures set out in the MP SOPS in place at the relevant time; and (d) The adequacy or otherwise of the training and awareness in the MP SOPs of the police that investigated Ben’s disappearance.

141. The concessions are proper, responsible and welcome. They have saved court time and allowed me to finalise the matter more efficiently which, of course, is a relief to Ben’s grieving family who have patiently endured the many delays in this matter. The approach taken by the Commissioner in this case, including during the first tranche, has given me comfort that there is a real commitment in the NSWPF to improving missing persons investigations. I was particularly assisted by DI Browne’s evidence which I discuss further below. The Castlereagh Local Area Command

142. At the time of Ben’s disappearance, CI Mureau was the Crime Manager attached to the Castlereagh LAC. He suggests that the first time he became aware of the investigation into Ben’s disappearance was on 14 January 2015.

143. During CI Mureau’s tenure as Crime Manager, commencing in October 2008 and up to and including Ben’s disappearance, there had been 99 missing person reports within the LAC. Of those 99 reports, 94 persons were found alive, three were found deceased following motor vehicle accidents and one was found drowned. Ben’s disappearance was the only unsolved investigation.

144. In his first statement, dated 18 July 2019, CI Mureau describes, inter alia, the extent of the Castlereagh LAC (“a total area of over 41000 square kilometres”), the number of open cases or investigations at the time Ben disappeared (“approximately 165”), and the fact that the LAC “was also dealing with a fatal quad bike accident involving an 8yr old child that occurred on the 18th of January and a sexual assault of a 14yr old child that occurred on the 21st of January”.

145. I accept CI Mureau’s evidence that policing isolated and remote communities is difficult, and that there are always resource challenges, but that nevertheless the two particular incidents that he averts to above occurred several days after Ben was reported missing, and after the critical period in which Ben might reasonably have been expected to be found alive absent any suspicious circumstances. I find below at [154] that insufficient priority was accorded to the investigation into Ben’s disappearance given the level of risk. This is a matter properly and responsibly conceded by the Commissioner. I do not accept that resource constraints and competing investigative priorities are a complete justification or excuse for the systemic deficiencies in this case.

The NSW Police Force Missing Persons Standard Operating Procedures

146. The MP SOPs that were in place at the time of Ben’s disappearance established the “minimum standards” for NSWPF officers in their day-to-day management of missing persons investigations. The MP SOPs are designed, as they themselves emphasise, “to maximise the chance that the [missing person] is found safe and well”. The now superseded MP SOPs provided a useful guide for the procedures to be taken by officers during each stage of a missing person investigation, including conducting a risk assessment and suggested responses depending on the outcome of that assessment.

Risk assessment

147. The MP SOPs do not explicitly mandate the use of the pro forma risk assessment matrix and questionnaire in Annexure 2 of the SOPs, but it is mandatory to record the outcome of any risk assessment and the SOPs are drafted in a manner that implies it is expected that the risk assessment form will be used.

148. The rationale for recording the risk assessment in writing is obvious: it allows for it to be vetted and reviewed by senior officers to ensure that all relevant factors have been considered and that the police response is commensurate to the risk rating; it can be reviewed by other officers in the event that the officer who conducted the initial assessment is unavailable; and it enables the result to be easily communicated to other commands and units as necessary (e.g. SCC or the Missing Persons Unit, as it was then known).

149. The MP SOPs also indicate that the risk assessment must be re-evaluated throughout the investigation, presumably to ensure, in the event of new information, or simply because of the passage of time, that appropriate investigative steps continue to be considered and initiated where possible.

150. The Commissioner has properly conceded that there was a failure of police to conduct a formal documented risk assessment during the initial stages of the investigation, and that this was contrary to the MP SOPs in existence at the time.

151. In her further statement of 5 September 2019, Inspector Bradbury conceded that she did not complete a written risk assessment as contemplated by the MP SOPs, however she states that she “completed cognitive risk assessments throughout the entire investigation” which, she says, were critical in her decision making process. Inspector Bradbury completed the risk assessment from Annexure 2 of the MP SOPs retrospectively and annexed it to this further statement. With the benefit of hindsight she determined that the risk posed to Ben when he was reported missing was “Medium”. Having reviewed the MP SOPs, Inspector Bradbury is confident that the protocols set out therein “would not have altered [her] course of action or response to the investigation”.

152. When SC Ramsay and Constable Gouhar attended the location of Ben’s car on 13 January 2015, the circumstances should have been regarded by police as materially significant. When Inspector Bradbury attended the scene two days later that significance had only increased and she told investigators that by that stage (i.e. 15 January 2015) she was concerned that Ben’s disappearance was “suspicious”. However, there is no evidence to suggest that the discovery of Ben’s car resulted in consideration of a documented risk assessment or indeed a recalibration of the “cognitive risk assessments” that had been undertaken by any individual officers.

153. In his statement, DI Browne gave evidence that the discovery of Ben’s vehicle should have resulted in a new risk assessment being completed, and noted that the new 2020 MP SOPs and COPS system will cause police to be prompted to consider, and if necessary conduct, a new risk assessment when additional information is added to the COPS report.

154. Counsel assisting put several factors related to the discovery of the car (which I outline at [77] above) to DI Browne during the further hearing. DI Browne concluded that, when those specific factors were taken into account, the discovery of Ben’s car would have contributed to an elevated risk rating and prompted an allocation of “High Risk” to Ben. I agree with and accept the submission made by counsel assisting that in light of the evidence available to police at the time that Ben was reported missing, and the criteria set out in the MP SOPS, the outcome of any risk assessment undertaken at the time that he was reported missing ought to have been that Ben was at “high” risk, especially in light of his long-standing dependence on alcohol and cannabis, his level of intoxication when he was last seen the geography of the area and the intense heat. It is likely that the failure of investigating police to adequately assess and document the potential risk to Ben resulted in a sub-optimal response by police in the initial days of the investigation.

The adequacy of training of investigating police in relation to the MP SOPs

155. The inquest received evidence about the inadequate awareness of police officers in Castlereagh LAC in relation to the MP SOPs, and the absence of any training those officers had received in relation to the MP SOPs. This is of particular concern in light of the evidence given by several officers as to the frequency with which persons are reported missing in the surrounding region. The Commissioner has conceded that many officers stationed at Lightning Ridge, including senior officers, lacked familiarity with the provisions of the MP SOPs and had not received training in relation to them.