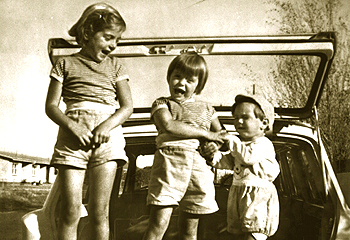

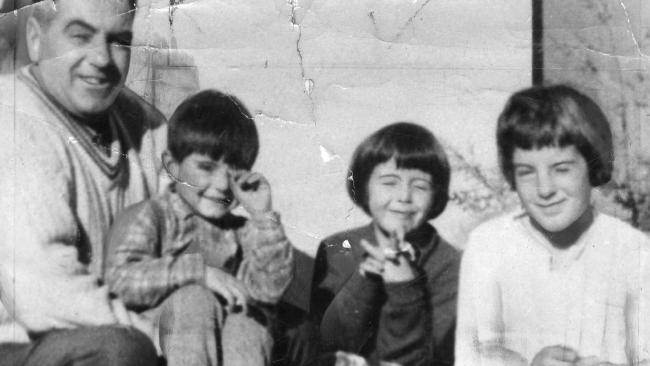

Jane, Arnna and Grant BEAUMONT

Missing - January 26th (Australia Day) 1966

Glenelg Beach, Adelaide,SA

Circumstances - at 10am on the morning of January 26th, 1966, brother and sisters Grant (4 years), Jane (9 years) and Arnna (7 years) Beaumont caught a bus from their home in Somerton Park Adelaide a short distance to Glenelg Beach. They were seen at 11am playing with a young, blonde man on the Beach, in the park opposite the Beach and then walking away with him behind the Glenelg Hotel. Jane bought ice creams for her brother and sister and paid for them with money her mother had not given her.

The local postman came forward and said that he had seen the trio, alone, walking up Jetty Road away from the beach and toward their home at about 3pm. They were laughing and holding hands.

The children were expected to return home on the midday bus but failed to catch this bus. They have not been seen since this date.

*Click here for a beautiful tribute video to the children

A Current Affair story, July 2013 - http://aca.ninemsn.com.au/article.aspx?id=8686565

Today Show story - http://aca.ninemsn.com.au/article.aspx?id=8686565

Police re-open inquiries into Beaumont children's disappearance

The World Today - Thursday, 3 February , 2005 12:30:00

Reporter: Nick McKenzie

KAREN PERCY: Now to one of the country's most notorious unsolved cases – the

disappearance of the Beaumont children from an Adelaide beach almost four

decades ago.

And last night cold-case detectives from across Australia interviewed

Victoria's longest serving prisoner about that case and five other unsolved

murders. Derek Percy has been in prison since 1969 after he was arrested for

killing a 12-year-old girl in Victoria.

Police there say interviewing him is only a preliminary step and may not

yield results. Nonetheless, the story is dominating newspapers and

reigniting speculation about a mystery that continues to haunt the nation.

Nick McKenzie reports.

NICK MCKENZIE: In Melbourne last night, Detectives from South Australia,

Victoria and New South Wales interviewed prisoner Derek Percy about his

possible connection to eight unsolved murders.

They include the murders of Christine Sharrock and Marianne Schmidt on

Sydney's Wanda beach in 1965, the murder of 6-year-old Alan Redston in

Canberra in 1966, the death of Simon Brook in Sydney in 1968 and the

disappearance of schoolgirl Linda Stillwell from St Kilda in the same year.

But police also interviewed 55-year-old Percy about the disappearance of the

Beaumont children – 9-year-old Jane, seven-year-old Arnna and 4-year-old

Grant from Glenelg beach on Australia day in 1966.

It's his possible connection to the Beaumont mystery that's sparked so much

attention this morning, although Victorian Police Chief Commissioner

Christine Nixon say the development is, at this stage, far from a

breakthrough.

CHRISTINE NIXON: I think that what we are doing is simply at the very

preliminary stages. When we've got some more information, when in fact the

investigators have had a chance to talk with this individual, then we'll

certainly make more information available as we can.

These are very difficult issues and areas. They're old cases, the family's

involved. You don't really want to raise their expectations until we're a

lot clearer. We clearly have information, and that information will be put

and when we've got further to say about the matter, we will.

NICK MCKENZIE: Prisoner Derek Percy was arrested in 1969 for killing a

12-year-old girl at Western Port Beach, but was found unfit to plead on the

grounds of insanity.

Today, the Age newspaper reported that in interviews with authorities over

the last few years, Percy has always remained evasive, but that notes and

diaries seized from his cell detail plans to abduct and kill children.

It's also believed police can place Percy near the scene of the Beaumont

children's disappearance and that there may be some similarities with the

crime he was arrested for and other unsolved murders.

Police are stressing the interview of Percy last night is, at this stage, a

very minor development. But it's not difficult to understand today's media

interest. The moment the Beaumont children disappeared, the nation was

fascinated.

This radio extract is from 1966:

RADIO EXTRACT: (Music in background) The biggest search of all was for the

Beaumont Children – Jane aged 9, Arnna 7, and Grant 4. They disappeared in

January after visiting a beach in Adelaide. In November, a Dutch

clairvoyant, Mr Gerard Croiset, said he believed the children's bodies would

be found under an Adelaide warehouse floor.

NICK MCKENZIE: Possible linking of Derek Percy to the Beaumont case comes

after a number of instances where other prisoners have been mistakenly

linked to the children's disappearance.

Associate Professor Colleen Lewis is a criminologist from Monash University.

She says new technology is breathing life into cold cases, but that there

are limits to what it can achieve.

COLLEEN LEWIS: With the advent of new technology with DNA and other

technology, there is the possibility these days that cases that have been

cold for some 20 or 30 years can be solved and we're seeing that more and

more.

NICK MCKENZIE: Is there a danger, though, in this case, that, because the

Beaumont case is really inscribed upon the nation's memory, that whenever

there's a snippet about any progress or any step or any development in the

case, that we get a bit ahead of ourselves and talk about a possible

breakthrough?

COLLEEN LEWIS: I think it has a lot to do with hope. I think that people

hope that we can solve this mystery, this Beaumont killing which has, as you

say, occurs, is brought back into our memory, time and time again when we

think that maybe this time there is a breakthrough.

KAREN PERCY: Criminologist Colleen Lewis from Monash University speaking to

Nick McKenzie.

New lead in Beaumont case

May 11, 2004 - The Age

New Zealand police are investigating claims that three children who

disappeared from Adelaide nearly 40 years ago may be living in Dunedin.

The disappearance of the Beaumont children has been one of Australia's most

baffling cases.

Jane, 9, Arnna, 7, and Grant, 4, left their home to go to beachside Glenelg

on Australia Day, 1966, and never returned.

Inquiries have now turned to New Zealand, after a man in his early 40s told

a woman at a butcher shop he thought he had lived next door to the missing

Beaumont children in Dunedin.

"He thought that because he recognised the children from a photograph he saw

in an article in The Truth some years later," New Plymouth police Sergeant

George White said.

Later, when the woman read a magazine article about the Beaumont case, she

realised the man's claims may have been valid and contacted police.

New Plymouth police Senior Sergeant Fiona Prestidge today said police wanted

to speak to the man to find out what he knew.

"We don't know whether it was some kind of community gossip or what," she

told ABC radio in Adelaide.

"It may not be (that) he physically believed he recognised them but it was

like he understood, he knew where they had lived and been raised.

"It's pretty speculative but then again, people might sit on information if

they don't appreciate the weight of it.

"We really want to identify this man in the first instance, although if he

doesn't come forward we've got avenues of inquiry to make down there

(Dunedin)."

Every major division of the South Australian police, along with Scotland

Yard and the FBI, have been involved in the Beaumont investigation, but

neither the children nor their bodies have been found.

Clairvoyants were also consulted as conventional police methods failed.

Despite a dizzying array of theories and rumour, only one major lead has

emerged.

Four witnesses, all of whom positively identified the children, said they

had been with a tall fair-headed man.

SA police today said the Beaumont file was still open, with a full-time

detective sergeant in charge of the case.

Every month the police received new calls about the Beaumonts but were yet

to hear from New Zealand police, a SA police spokesman said.

"At this stage it's just a stalemate and we're still waiting," he said.

-AAP

Police keen to solve 40-year mystery

Wednesday Jan 25 14:00 AEDT

It's been 40 years since the three Beaumont children vanished from an

Adelaide beach, but police have not given up hope of solving the mystery.

Jane, Arnna and Grant Beaumont were last seen with a tall, fair-haired man

at Glenelg beach in 1965.

Detective Superintendent Peter Woite said police still receive regular

tip-offs about the siblings.

He said it remains very much an "active case" even though Australia Day

marks the 40th anniversary of their disappearance.

"Information is received on a regular basis regarding this matter," Supt

Woite said.

"Any information received is investigated, (but) at this stage there is no

new information."

The disappearance of Jane, then aged nine, Arnna, 7, and Grant, 4, is South

Australia's most enduring mystery.

Police have followed up more than 10,000 clues and rumours, including one

early report that the children were living on the Mud Islands, in Victoria's

Port Phillip Bay.

An Adelaide warehouse was twice excavated after a Dutch clairvoyant said the

children were buried under the building's brick kiln.

There were also suggestions they were alive and living in New Zealand.

Police have travelled to Tasmania and Victoria to interview convicted

killers James O'Neill and Derek Percy but their investigations drew blanks.

Supt Woite said the case could still be resolved and urged anyone with

information to contact Crime Stoppers on 1800 333 000.

New light on missing kids

Frank Walker - SMH

October 15, 2006

THE answer to the 40-year-old mystery of what happened to the missing

Beaumont children is buried in the twisted mind of a child killer locked in

a Tasmanian jail, a retired detective says.

Former Victorian detective Gordon Davie spent three years speaking to

convicted child killer James Ryan O'Neill, 59, to win his confidence before

filming him for an ABC documentary, The Fishermen, to be broadcast on

October 26.

Mr Davie said although there was no evidence to link O'Neill to the

disappearance of the Beaumont children - Jane, 9, Arnna, 7, and Grant, 4 -

from an Adelaide beach on Australia Day, 1966, he was convinced O'Neill was

to blame.

"I asked him about the Beaumonts and he said: 'I couldn't have done it. I

was in Melbourne at that time.' That is not a denial."

Now no one will ever know if an old man called Arthur Stanley Brown was Australia's worst serial child killer. The retired Townsville carpenter, charged in 1998 with a notorious double murder - and suspected of others - has died, aged 90.

His death ends any chance of proving he was guilty, as police firmly believe he was, of the rape-murder of Mackay sisters Judith, 7, and Susan, 5, in Townsville in 1970.

But it also leaves unanswered questions hanging over other families robbed of their children.

Did Brown, subject of a Sunday Age investigation in July last year, abduct and kill other children over several decades - and not just in Queensland, where several cases remain unsolved?

Is it just a coincidence that he matched the descriptions of a thin-faced, middle-aged man who abducted Kirste Gordon and Joanne Ratcliffe from an Adelaide football game in August, 1973? Was he the same thin-faced man seen with the Beaumont children before they vanished from an Adelaide beach in 1966?

Brown not only took his secrets to the grave - he ensured his own death was kept quiet. He left instructions that no funeral notices be placed.

Only one of his second wife's daughters knows any details of his funeral, but when The Age reached her yesterday she wasn't talking. All that is known is that after his wife, Charlotte, died last April, he was put in a home at Malanda, north of Townsville. He died alone on July 6.

Brown has no known living blood relatives. His only kin are the children and grandchildren of two widowed sisters he married - the second one soon after the suspicious sudden death of the first.

Brown's name hit the headlines in 1998, after a woman broke a 30-year silence to tell police he had molested five children related to his first wife - often at the same spot where the Mackay sisters' bodies were found in 1970.

He had also owned a car in 1970 with one odd-coloured door, matching a description of one driven by the man who had abducted the Mackay girls. Relatives believe he replaced the door and buried it days after the murders.

Brown's first wife, Hester, crippled by arthritis, became a virtual prisoner in their neat fibro and timber house in Rosslea, an old suburb of Townsville. She died suddenly in May, 1978, from injuries Brown claimed she suffered in a fall.

Police believe the family doctor wrote out a death certificate without examining the body, which Brown had cremated immediately. Already close to Hester's younger sister Charlotte, a mother of five, he married her soon after.

Brown, a fit, wiry man, was unusually strong and obsessively neat, wearing pressed clothes to work as a maintenance carpenter on state government buildings. The Mackay sisters' clothes were found neatly folded near their bodies.

The evidence against Brown was strong but circumstantial. He twice blurted cryptic confessions to the Mackay girls' murders, once to a workmate and once to a stranger in a pub.

A Queensland jury could not reach a verdict in 1999, and a new trial was blocked on the ground that he was too senile to be tried again.

If Brown was a monster, what made him so? A stepson, Robert Neilsen, says Brown talked incessantly - but rarely mentioned children. "Except once, when the subject of little kids came up and he started to cry and said we had to look after the little children."

But Neilsen has no sympathy for the man his mother stuck with to the end of her life. "I can't believe such an insignificant little arsehole had such a profound effect on so many people's lives."

Victorian prisoner Derek Percy is suspected of

having been involved in the disappearances of the Beaumont children from

Adelaide and Linda Stilwell from St Kilda.

Photo: Simon O'Dwyer

The evidence, rediscovered during a cold-case unit investigation into the 1968 disappearance of Linda Stilwell, 7, from the St Kilda foreshore, has convinced detectives that Percy is a serial killer who could have abducted the Beaumont children in Adelaide.

Percy, now 58, murdered Yvonne Tuohy, 12, after he abducted her from the beach at Warneet on July 20, 1969.

He is now a suspect in the murders of Christine Sharrock and Marianne Schmidt on Sydney's Wanda Beach in January 1965; the disappearance of the three Beaumont children, Jane, 9, Arnna, 7, and Grant, 4, in Adelaide in 1966; the murder of Allen Redston, a six-year-old grabbed in Canberra in September 1966; Simon Brook, 3, killed in Sydney in 1968; and Linda Stilwell.

The breakthrough came when detectives re-examining the Tuohy file found a hand-written note that included the registered identification number of a policeman.

Detectives found the retired policeman was a school friend of Percy's and had visited him in a police cell in 1969 at the request of the homicide squad.

When interviewed by the cold-case unit, he said Percy had implicated himself in the abductions of Linda Stilwell and the Beaumonts and the murder of Simon Brook.

The policeman said Percy told him he was in the areas where the crimes were committed but couldn't remember if he killed the victims.

Psychiatric reports show that Percy has the capacity to repress memories of his crimes.

Despite the admissions by Percy, the former school friend was not asked to make an official statement at the time because it had no bearing on the Tuohy case.

But as part of the cold-case unit's review, an investigation involving four police forces, called Operation Heats, has found further evidence linking Percy to the cases. It includes:

■A remarkable similarity between Percy and identikit portraits issued at the time.

■Identical references in writings seized from Percy in 1969 and the unsolved murders.

■Police confirming Percy was in the areas in which several of the murders were committed at the time of the offences.

■An article of clothing that may link him to one of the cases and a connection to a murder weapon in another.

■Percy having maps where some of the murders and disappearances occurred.

■Evidence of a failed attempt to abduct a girl on the Mornington Peninsula just months before the Tuohy murder.

One policeman involved in the case is convinced that Percy has struck many times.

Inspector Tim Attrill served with Percy when they were both young sailors on the training frigate HMAS Queensborough, and was called in by Operation Heats when the suspect was again interviewed in 2005.

"I have no doubt that if he ever gets loose he will do it again," the inspector said.

"After 35 years in the job, I would like to think I have a handle on people and nothing has changed with Percy except he has learned to play the game better.

"He is a disaster waiting to happen. He is highly intelligent, one of the most intelligent people I've met. He is cold, without emotion and looks straight through you with his crazy eyes."

Inspector Attrill said many former sailors were disgusted that Percy still received a pension from the navy and had accrued nearly $200,000 since his arrest.

"I know there will be a submission to the Government to cancel his pension. Why should taxpayers support that animal?"

Percy was found not guilty of Yvonne Tuohy's murder on the grounds of insanity in 1970 and has failed to have courts set him a minimum term. He has told police he still hopes to be freed.

"The only way he should be allowed out is in a pine box," Inspector Attrill said.

The evidence against Percy is considered so compelling in the case of Simon Brook that NSW Coroner John Abernethy has referred it to the Director of Public Prosecutions to see if sufficient evidence exists to lay charges. Detective Sergeant Brian Swan, of Adelaide's Major Crime Investigation Branch said Percy "remains a person of interest in the disappearance of the Beaumont children".

NSW Detective Sergeant Adam Barwick said: "In my opinion, Derek Ernest Percy is responsible for the murder and mutilation of Simon Brook." Senior Detective Wayne Newman, of Operation Heats, concluded "that Derek Ernest Percy did murder Christine Sharrock and Marianne Schmidt, may have abducted and murdered Jane, Arnna and Grant Beaumont, did murder Simon Brook, and did abduct and murder Linda Stilwell. He remains a suspect for the murder of Allen Redston and he cannot be eliminated."

A court has transferred Derek Ernest Percy into police custody this morning so detectives can question him about a series of unsolved child murders - including the unsolved Wanda beach murders more than 40 years ago.

Melbourne magistrate Belinda Wallington said she was satisfied it was in the interests of justice for Percy, 59, to spend eight hours with the detectives at the homicide squad headquarters in St Kilda Road today.

Percy, who was in court for the brief hearing, sat quietly throughout, occasionally looking around the courtroom.

A detective from Victoria Police's cold case unit told Melbourne Magistrates Court police wanted to question Percy about documents they found at a South Melbourne storage facility.

He said the documents could relate to the abduction, disappearance and murder of Christine Sharrock, Marianne Schmidt, Linda Stillwell and the three Beaumont children, Jane, Arnna and Grant.

Police discovered 35 boxes of files, clippings and handwritten diaries concealed by Percy in a South Melbourne self-storage warehouse that he has rented for 20 years. They also found razor blades similar to one used to mutilate a victim.

The material includes newspaper articles on sex crimes,

Percy managed to collect and transfer the material from jail to his private collection, despite being one of Australia's most violent sex criminals and judged too dangerous for release.

Police now know that Percy, a former naval rating, has maintained

storage facilities in Melbourne since the early 1970s.

He was ordered to remain in custody indefinitely when found unfit to plead on the grounds of insanity for the murder of Yvonne Tuohy, 12, who he grabbed from the beach at Warneet, south-east of Melbourne, on July 20, 1969.

He is also a suspect in the murders of Christine Sharrock and Marianne Schmidt on Wanda beach in January 1965; the disappearance of the Beaumont children, Jane, 9, Arnna, 7, and Grant, 4, in Adelaide in January 1966; the murder of Allen Redston, a six-year-old grabbed in Canberra in September 1966; Simon Brook, 3, killed in Glebe in May 1968; and Linda Stilwell, 7, abducted from Melbourne's St Kilda foreshore in August 1968.

The bodies of Christine Sharrock and Marianne Schmidt, two friends aged 15 from West Ryde, were found in the dunes of windswept and deserted Wanda beach the day after they disappeared.

A taskforce found credible evidence leading investigators to say that Percy remains a person of interest in the unsolved cases.

Following the discovery of the documents, police are expected to apply for permission to question Percy, who is in Port Phillip Prison, about the unsolved murders. He is expected to be interviewed by Victorian and NSW detectives.

Since he was a teenager Percy has written diaries that detail his violent sexual impulses. The first few were destroyed by his parents, but after his arrest at HMAS Cerberus, the navy training base on Victoria's Mornington Peninsula, for the murder of Yvonne Tuohy, police found more writings connected with plans to abduct and torture young victims.

When he was jailed, Percy became a model prisoner. But a search of his cell in September 1971 found he had compiled elaborate blueprints of planned sex crimes along with pictures of children, obscene notes and complex charts showing abduction plots.

Percy has claimed that a prison psychiatrist, now dead, urged him to write down his fantasies for "therapeutic purposes". He has also said repeatedly that he has not had any violent fantasies since that time.

In 1998, when Percy began legal moves to seek his freedom, the Supreme Court was told that "since 1971 Mr Percy has never written anything which could be indicative of any sexual fantasy".

But the discovery of the secret storage holdings show that after the material was discovered in his cell Percy began to hide his writings and clippings by sending them out of the prison.

Police say the evidence inside his private warehouse indicates Percy has not changed but chose to hide incriminating material that would destroy his hopes for release. "If he has stored them he must believe he will get out so he can recover them," a senior policeman said.

Police now know that Percy has moved material from prison since the early 1970s - first to a rented lock-up in the Melbourne suburb of Pascoe Vale, and for the past 20 years, to a self-storage unit in South Melbourne.

The documents, kept in tea-chests and cardboard boxes, include material that police say may implicate Percy in the murders of Linda Stilwell and the Wanda beach victims.

They have found a 1978 street directory where a line has been drawn through the St Kilda Pier where Linda Stilwell was abducted 10 years earlier and a pornographic lesbian cartoon on which Percy has written the word "Wanda" across the top.

In 2005 the NSW Coroner, John Abernethy, held an inquest into the murder of Simon Brook. Percy refused to give evidence on the grounds of self-incrimination.

Some of Percy's writings, including those seized in South Melbourne, detail abducting a young boy and inflicting similar injuries to those found on Simon Brook's body. Police also found in Percy's collection a kit filled with old-style razor blades, the same type used to mutilate the young victim.

Mr Abernethy referred the case to the NSW Director of Public Prosecutions to see if there was sufficient evidence to charge Percy, but the DPP has decided not to proceed.

Victoria's Coroner, Graeme Johnstone, is now set to open an inquest into the murder of Linda Stilwell. Percy will be the only known suspect. Mr Johnstone will also examine material that links Percy to the interstate cases.

Police believe the storage boxes contain Percy's possessions at the time of his arrest, material smuggled from jail in the 1970s and official documents, including court records that have been legitimately transferred over the past two decades.

Earlier this month a court in Victoria found officially that Linda Stilwell had been murdered. The magistrate, Susan Wakeling, granted the Stilwell family an application for crime compensation.

Percy has received a navy pension since his arrest, has nearly $200,000 in the bank and has successfully invested in gold. He has used part of his income to rent the South Melbourne storage area.

Among the items seized by police was an extensive stamp collection valued at several thousand dollars compiled while Percy was in prison.

THE young sailor slumped on the bed in the watch-house cell was crying with self-pity when an old school friend walked in. It was the first familiar face he had seen since his arrest two days earlier at the Cerberus naval base over the murder of a 12-year-old girl taken from a nearby beach.

But the "friend" was not there out of concern. He was now a young policeman and the homicide squad had sent him to persuade the prisoner to talk about past crimes. The suspect was Derek Ernest Percy — arrested trying to wash away his guilt and a dead girl's blood at the navy base, hours after Yvonne Elizabeth Tuohy had been abducted at Ski Beach, Warneet, and then molested, tortured and murdered.

When Percy grabbed her, he also tried to abduct her friend, Shane Spiller, 12, who escaped by threatening Percy with a tomahawk and running away.

The nature of the crime led detectives, including elite investigator Dick Knight, to conclude this was not Percy's first attack.

It was 1969 and Australia was reeling from a series of child abductions and murders over the previous four years.

Christine Sharrock and Marianne Schmidt were murdered on Sydney's Wanda Beach in January 1965; the Beaumont children (Jane, 9, Arnna, 7, and Grant, 4) were abducted in Adelaide in 1966; Allen Redston, 6, was murdered in Canberra in September 1966; Simon Brook, 3, was killed in Sydney in 1968; and Linda Stilwell, 7, was abducted from St Kilda in August 1968. All cases remain officially unsolved.

For nearly 40 years police have wondered if Percy was responsible for nine murders. Now, after a complex investigation involving old memories and new techniques, they have built a compelling case against Australia's longest-serving prisoner.

But in July 1969, the novice policeman was supposed to listen to his old schoolmate in the hope he would open up. And it almost worked. The policeman left the force 18 years ago to return to country Victoria and a quiet life. But when contacted by cold case unit detectives he immediately knew why.

Unprompted, he recalled his last conversation with Percy.

"He had been sobbing and was very distraught.

"He said, 'Looks like I've f---ed up this time'. I said, 'It certainly looks like it, Derek'.

"Derek put his head in his hands for a while, then he looked up at me again and he had tears in his eyes and panic written all over his face. He also looked at me with a plea for help."

The schoolmate gently asked: "Were there any others, mate?"

"Derek put his head in his hands and began to sob again. He said, 'I cannot remember'."

It was the same response he'd given two days earlier to homicide detectives over the Tuohy murder, until confronted with incontrovertible evidence.

The schoolmate, a policeman for barely six months, pushed on. "Well look, Derek, I'll ask you about some of the ones that I know about. You don't have to say anything. If you remember I will jot it down and it could be used in court."

Asked about Linda Stilwell, Percy again said his memory was blank but then made the first of several telling admissions: "Yes, I drove through St Kilda that day. I had been at Cerberus in the afternoon and was driving along the esplanade on the way to the White Ensign Club for some drinks."

Asked if he killed her, he said: "Possibly, I don't remember a thing about it."

Questioned on Simon Brook, he admitted being in Sydney at the time and said he had driven his brother to work, turning off at the railway cutting where the body was found.

The policeman, who cannot be named because of a suppression order, pressed him: "So you drove past the same spot in Sydney on the day Simon Brook was killed." Percy said, "Yes".

Question: "Do you remember if you killed him?"

Answer: "I wish I could. I might have. I just don't remember."

Question: "What do you know about the Beaumont children in South Australia."

Answer: "I was in Adelaide at the time."

Question: "You were what? You remember being in Adelaide when they went missing?"

Answer: "Yes."

Question: "Whereabouts were you when they disappeared?"

Answer: "Near the beach. But nothing else."

Percy was placing himself at each crime scene. Perhaps with more time and pressure he would confess, as he had done over the Tuohy murder.

But at that moment, the watch-house keeper told the junior constable he had no business being in the cell. The young copper said he was on homicide squad business, but when he turned back to Percy the spell was broken. The killer knew his former schoolmate was no longer a friend, but trying to find the secrets of his dark past.

In April 1970, Percy was found not guilty of Yvonne Tuohy's murder on grounds of insanity. He has never been charged with any other crime. But prison officers, psychiatrists, judges, police and welfare officers consider him the most dangerous man in Australia.

The policeman, now long retired, has never been in doubt. When he left the cell that day, another former schoolmate, called to Russell Street to make a statement, saw him. He was upset and shaking. "That f---ing bastard, I hope they hang him," he said.

FOR the cold case unit, going over Linda Stilwell's disappearance from St Kilda 36 years earlier was meant to be a case of tidying up loose ends to provide the coroner with a summary of facts. With no real chance of finding a body, the unit did not want to waste time needed for other cases. But when Senior Detective Wayne Newman started to delve in January 2004, he began to discover evidence that pointed to Percy.

For Newman, the "quick" investigation turned into a two-year quest linking Percy to baffling murders that have long seemed unsolvable. It would involve police from four forces, psychiatrists and forensic experts.

The investigators, many of whom were not born when the murders were committed, co-operated in a unique operation, codenamed Heats. To establish that Percy had killed more than once, detectives retraced the life of the quiet country boy who became a monster.

ERNEST PERCY was a NSW railway electrician for nearly 25 years before taking a job with the State Electricity Commission in Victoria, first moving to Chelsea, then relocating his young family to Warrnambool in 1957.

Ernest Percy's passion was sailing. His eldest son, Derek, just nine when they moved to Warrnambool, shared the hobby.

In 1961, Percy senior was promoted and the family went to Mount Beauty, near Bright. The Percys took caravan holidays, often travelling interstate to yachting competitions in their V8 Studebaker. Much later, police would track these holidays against their murder map from the 1960s, with intriguing results.

In 1961, Derek started at Mount Beauty High School. The school uniform included a green and gold striped tie. Other students noticed that Derek's tie was made of coarse fabric and not a perfect match for the school pattern — although it was close enough.

He became a friend of a local farmer's son who had also just moved to town and was one of few who liked Percy. Others found him intense, abrupt and at times unsettling. But no one thought he was dangerous. Yet.

When police from Operation Heats approached the friend, he told them: "One thing that stood out about Derek was that he was very intelligent. Most or nearly all of us at school had to work and study very hard but not Derek." He also noted that Percy was shy and never had a girlfriend.

Banned by his worried parents from playing football, Percy would sometimes borrow a friend's gear for the occasional game, convincing his mate's mother to wash the clothes so he would not be caught.

If the Percys were over protective, it was understandable. Their third-born, Brett, died from diphtheria when aged only 10 months. They were to have three surviving sons.

Derek earned his pocket-money working in the tobacco fields with friends — buying a second-hand red bike with racing "ram's horn" handlebars.

He carried his sharp knife everywhere, but in country Victoria that did not make him unusual. In the 1960s a pocket-knife was more a tool than a weapon, used to solve a problem rather than create one.

But when Percy used his to help a mate make running repairs to the sole of a shoe during a handball game, he showed a glimpse into his future.

"I remember Derek getting his pocket-knife out and telling me that he would cut (the sole) off … Derek began to cut the sole off my shoe and all of a sudden the blade went into Derek's left thigh about three quarters of an inch (about two centimetres). The blade went deeply into his thigh and I recoiled back in surprise.

"I was amazed that Derek just looked fascinated with what had happened. He didn't scream, cry or really show any sort of emotion that you would expect from someone with a knife in their leg.

"I thought his reaction was extremely odd," the friend said. "He seemed happy about it."

Kiewa Valley's hydro-electric plant was no Snowy Mountains Scheme but it gave tradesmen the chance to raise families in one of Victoria's prettiest spots.

There was little violent crime in the town of fewer than 2000 people, no need to lock houses or cars. But in late 1964, a small crime wave began: women's underwear began to disappear from clothes lines — and Derek Percy was rumoured to be the thief. Until then he had been a model student and a school prefect, but in 1965 his grades plummeted.

Ernie Percy threatened to sack any hydro worker who suggested his son was the phantom "snowdropper", but by late 1964 at least two locals knew that Derek was the culprit and that he was much worse than just a petty thief. He was dangerously disturbed and, they believed, a potential killer.

On a warm Sunday, two teenagers, Kim White and Bill Hutton, walked to a local swimming hole. There they saw what they thought was a girl in a petticoat. Then they realised it was Percy in a pink negligee.

"Well, at least it fits," one joked to his mate. But any humour was lost when Percy began to slash wildly at the clothing, then cut and stabbed at the crotch of a pair of knickers.

Hutton could see Percy's face. "I would describe Derek's eyes as being full of excitement, a glazed look, but I recall there was something very cold and sinister in the look," he told police much later.

The boys told a teacher the next day and were accused of making up stories. They confronted Percy but he denied everything. Most fellow students thought their story was fabricated. After all, Percy was the obedient student and his accusers loved a little mischief.

The following year Ernie Percy took a job with the Snowy Mountain Scheme and moved his family to Khancoban in NSW, but to allow Derek to finish school at Mount Beauty the teenager boarded with another family.

The woman who lived next door remembers how the new boarder would watch her hang out washing. One Saturday she took her daughters, then aged seven and nine, to visit a relative. When they returned they found the girls' wardrobes had been rifled through and their underwear and dresses stolen.

The mother reported the theft to the police, who asked her if she suspected anyone. She suspected Percy but did not want to say so, she admitted years later.

A few weeks later a local found some of the dresses in a bundle hidden under some bushes. With it was a girl's doll, with the eyes "blinded" and newspaper clippings of women in bikinis. The women's eyes were pencilled out and the bodies mutilated with razor blades. The slashes would match some of the wounds inflicted on the children murdered around Australia in the 1960s.

The blinded doll belonged to the girl next door to where Percy was living.

Percy moved from Mount Beauty to join his family in Khancoban after he failed his exams in 1965, a strange result for a student with an IQ of 122.

In his entry in the Mount Beauty school magazine he revealed a little of his concealed thoughts. His favourite saying was: "It depends." Perpetual occupation: "Isolating himself." Ambition: "Playboy." Probable fate: "Bachelor." Pet aversion: "Girls."

When Percy left Mount Beauty the "snowdropping" stopped, only to begin near his new home in Khancoban. There were also reports of a Peeping Tom.

While at Khancoban a neighbour found that Percy had lured her six-year-old daughter into the family caravan to sexually assault her. The girl's father decided to deal directly with Ernie Percy, who promised it wouldn't happen again. And it didn't. At least not there.

While both parents said they thought their eldest son was shy but normal, deep down they had growing fears.

One Mount Beauty local said that while Mrs Percy allowed her middle son freedom, the elder brother was kept on a tighter rein. "Derek had to get permission to go anywhere with us outside of school hours and she would question his intentions."

Ernie Percy would later tell NSW police he had once found Derek dressed in woman's clothing. The parents also found some disturbing sexual writings by their son and immediately burnt them. Later Percy's grandmother found letters filled with "rude" thoughts. Percy denied they were his. Again they were burnt.

Percy began writing down bizarre and violent sexual fantasies in 1965 — around the time his school grades collapsed. He continued the self-incriminating habit for years.

Much later police would allege the writings were plans for the crimes he was to commit and directly linked him to the series of unsolved child murders.

At the end of 1966, having repeated year 11, Percy was ready to leave school. His father also decided to leave the mountains to move into private enterprise. He invested his payout on a Shell service station in Newcastle.

Derek tried year 12 in a NSW school, dropped out, worked at the service station, and in November 1967 joined the navy, graduating top of his class a few months later.

Nearly four decades later, detectives started trying to piece together his movements around Australia over the crucial four-year period in the 1960s.

They knew the Percys often took their caravan to holiday near beaches during yachting regattas. They also could prove Percy was harbouring thoughts of molesting and killing children at the same time as the series of shocking abductions were carried out in four states and territories — and with one exception — all near beaches.

But was it simply a series of coincidences? How could a teenager from country Victoria grab kids hundreds of kilometres away? And how could a young sailor murder and return to his base undetected?

On a windy Monday — January 11, 1965 — teenage neighbours Marianne Schmidt and Mary Sharrock went to Sydney's popular Cronulla Beach area with Marianne's four younger siblings. After a picnic, the younger children stayed in a sheltered area at Wanda Beach and the two 15-year-olds started talking to a fair-haired youth.

Peter Schmidt, 10, saw his sister and her friend with the teenager. His brother Wolfgang, 7, had also seen them talking to the boy earlier. The youth had a knife in a sheath and carried a spear.

The girls' mutilated bodies were found the next day, partially buried near a sand dune.

As in the Tuohy case, the victims were taken from the beach and dumped nearby. The crotch area of one of the girls' bathers had been cut. Percy had been seen slashing female underwear at Mount Beauty in late 1964 — just weeks earlier.

Some people remembered that the Percys had gone to Sydney for a holiday that summer. The mother of one of Percy's closest friends in Mount Beauty told detectives that she had always suspected that Percy might have been "a suspect in that case".

Ernie Percy took holidays to coincide with yacht races around Australia. That summer the national yachting regatta was at Botany Bay Yachting Club — near Wanda Beach. Percy's grandparents lived walking distance from the West Ryde railway station where the two girls caught the train.

After police arrested Percy at Cerberus, they found a diary in which he described his urges to sexually abuse, torture, murder and mutilate children. They also found drawings of naked children and women.

In one excerpt, Percy wrote he would force one of his victims to drink beer. Autopsy results showed that Mary Sharrock had a blood alcohol reading equivalent to drinking about 300 millilitres of beer.

In his murder blueprint he wrote about abducting and killing "Two girls at Barnsley", a NSW beach in northern NSW. Police believe it was code for Wanda Beach.

It was 1966 and Percy had moved to Corryong High when classmate Wayne Gordes decided to tease the new student after he saw the obvious resemblance to the photo-fit. "I jokingly thought to myself 'That's Derek', because of the description and I knew that they went to a beach in Sydney.

"A group of us were standing in the quadrangle when Derek Percy walked past. I said, 'We know it was you that killed those girls in Sydney. You have the same haircut and we know you were there.'

"With that Derek went berserk. He said, 'Don't you say that' … I think he wanted to fight me for what I had said. I had never seen Derek behave like that before."

ON WEDNESDAY, January 26, 1966, the Beaumont children — Jane, 9, Arnna, 7, Grant, 4 — caught the bus from their Somerton Park home to Glenelg Beach, Adelaide. They left about 9.45am; their mother, Nancy, expected them home about midday.

A friend of Jane's saw them sitting near the Holdfast Bay Sailing Club about 11am. A man was seen talking to them and at 11.45am the children bought a pie and two pasties from a bakery in Jetty Road.

The man almost certainly gave them cash for the food as they paid with a £1 note — more money than their mother had given them. They were never seen again.

The suspect was described as in his 30s with light brown, short swept-back hair parted on the left side, a thin face and clean-shaven. He was suntanned and wearing blue bathers with a white stripe down the side.

Could it have been Percy? He was only 17 at the time but was sometimes mistaken for being older. His writings showed he planned to give food to the children he would kidnap before killing them. The Beaumonts were in the age group Percy fantasised about and they went missing from the beach, as did Yvonne Tuohy, Marianne Schmidt, Mary Sharrock, and Linda Stilwell.

Some elements of the description fitted Percy, some didn't. The original sketch of the suspect was done by a non-police artist and is not considered accurate.

Was Percy in Adelaide? He told police he had been there on holiday but couldn't remember when. His brother confirmed they had been there. The mother of one of Percy's friends told police: "I can also recall that Derek travelled to Adelaide on holidays by plane on one occasion."

Asked by detectives in 2005 if he was in Adelaide when the Beaumonts went missing he answered, "I don't know".

They then asked if he was blocking out thoughts "because something horrible happened in Adelaide and you don't want to remember it?" and he said it was possible.

Five days after the Tuohy murder he was interviewed by prison psychiatrist Dr Allen Bartholomew who found Percy had the capacity to repress memories of the crimes he committed. He said that if Percy had been arrested a week after the murder he would no longer have been able to recall what he had done.

Without bodies or a confession, Percy heads a short list of suspects for the Beaumont children. Evidence is too scanty to prove or disprove his involvement but the similarities of the crime with Percy's modus operandi are striking.

Detective Sergeant Brian Swan from Adelaide's major crime investigation branch said Percy remains "a person of interest in the disappearance of the Beaumont children".

And Dr Bartholomew observed after interviewing Percy: "It is not beyond the bounds of possibility that there is some other great harm been done in the past and there is no way of knowing it."

ON SEPTEMBER 27, 1966, Allen Geoffrey Redston, 6, left his home in the Canberra suburb of Curtain to go to the nearby milk bar to buy an ice-cream.

The following day his body was discovered concealed in reeds by a local creek. The body was hog-tied and had plastic wrapped around the throat.

A police investigation found that in the days leading up to the murder, a fair-haired teenager had been forcing boys to the ground, tying them up and placing plastic over their heads in an apparent attempt to asphyxiate them.

The identikit closely resembled Percy and the suspect was riding a distinctive red pushbike with "ram's horn" handlebars — the type Percy rode at Mount Beauty and took with him on caravan holidays.

When Dick Knight questioned Percy in 1969, he confirmed taking a family holiday in Canberra in 1966. Police established he had a Canberra relative but have found no records to pinpoint the exact date of the holiday.

Percy's writings detail using plastic and his plans to tie up and asphyxiate victims. Both Redston and Tuohy were tied and gagged when their bodies were found.

Percy was the product of an otherwise stable family. But there was a secret. When Derek was young and being cared for by his grandmother, she would use a bizarre form of punishment: she would lock him in a room and hog-tie him — feet and hands bound the way little Allen Redston's were.

One item found at the crime scene puzzled the original investigators. Along with other material used to used to bind the child was a tattered green and gold striped tie. It was similar to the Mount Beauty High School ties but was made of a distinctive coarse cloth, like hessian. It matched the school tie Percy no longer needed after transferring to Corryong High earlier that year.

That is one reason why federal police say that Percy cannot be eliminated "as a person of interest in relation to the death".

AFTER three months in the navy, Percy was posted to the aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne on March 9, 1968. But the ship was in Cockatoo Dry Dock at Sydney Harbour for a year-long refit and the junior sailor was assigned fire sentry duty.

He lived at the naval base at nearby Garden Island and commuted through the suburb of Glebe to the dock. On Saturday, May 18, 1968, Simon Brook, 3, went missing from the front yard of his family home in Alexandra Lane, Glebe. The house was next to Jubilee Park on Sydney Harbour, close to beach and yachts.

A truck driver later said he'd seen a boy matching Simon Brook's description holding a young man's hand near Jubilee Park.

The mystery man was well-groomed with a neat haircut, and an identikit image has a startling similarity to a photograph of Percy in his school year book.

The little boy's body was found behind a building site about 350 metres from the Brooks' home. There were several signature injuries similar to those inflicted on Yvonne Tuohy. When police examined the scene they found two Gillette razor blades probably used in the attack. The same brand was issued to sailors.

But the most damning evidence comes from Percy's own hand. In his diary, he wrote of abducting and killing a three-year-old "baby" and described in detail the exact injuries inflicted on Simon Brook. Detectives say it is a virtual confession.

When Dick Knight interviewed Percy in 1969 he asked him, "Did you kill Simon Brook?", and Percy said "I could have". When Percy talked to the young policeman who was his old schoolmate, he admitted he had been in the Glebe area at the time "turning off at the railway cutting where the body was found".

Only someone with a detailed knowledge of the area would know that Simon Brook lived near a railway cutting, and if Percy turned off at the railway cutting he would have driven straight past the Brooks' street.

Crime profiler Detective Senior Sergeant Debra Bennett concludes "there is all likelihood that the offender for Simon Brook's murder and the offender for Yvonne Tuohy's murder is one and the same".

And NSW Coroner John Abernethy agrees. A new inquest was held in 2005 and after just two days he found the evidence so compelling he closed the hearing and referred the case to the Director of Public Prosecutions. Percy was flown to the inquest but chose not to give evidence on the grounds of self-incrimination.

Abernethy said he believed there was a "reasonable prospect … that a jury would convict a known person in relation to the offence". Charges might still be laid.

LINDA STILWELL was four when her family arrived in Melbourne from England on the migrant ship the MV Fairsky in April 1965. Linda was the second youngest of four children. For her mother Jean and father Brian the new start could not save their marriage. In July 1968, Brian left for New Zealand with their youngest child, Laura. Jean stayed in Melbourne with the other three, took a job at an Albert Park hotel and moved into a flat in nearby Middle Park.

On Saturday, August 10, 1968, she told her children to stay home while she went grocery shopping. But the lure of the beach was too much for the two eldest, who wanted to explore the new neighbourhood.

When Mrs Stilwell arrived home about midday, Karen, 11, and Gary, 9, had left. She dressed Linda, 7, and told her to go and find her brother and sister to bring them home for lunch. Three hours later Karen returned to say Gary and Linda were fishing on the St Kilda Pier.

About 4pm Gary returned, saying Linda had gone to Little Luna Park to "look at the rifles" with some boys. His mother sent the boy back to find his sister but he came back saying he thought she might have gone to the police station to collect some fishing rods.

Stilwell rang the police and was told that two boys had been in to get the rods but there was no sign of a little girl. Three small boys told police they had last seen Linda at Little Luna Park.

Two days later a woman contacted police and said she had seen a girl matching Linda's description rolling down a grassy hill near the Lower Esplanade. She said she saw a man near her. She described him as having an olive complexion, thin features and wearing dark clothing.

She said the man was wearing "a deep navy blue, almost black, spray jacket, similar to that worn when sailing. The man was sitting with his legs crossed looking out to sea quite intently, but appeared relaxed."

About 80 suspects were questioned but no leads came up. Linda was never seen again.

Percy had transferred to the troop ship HMAS Sydney (based in Melbourne) on July 1, 1968, but was on leave for 18 days from August 5, five days before the abduction.

After Percy was arrested for the Tuohy murder the following year, the woman witness opened the paper to see the picture of the suspect. He was wearing a dark spray jacket. "I got the biggest shock of my life. This was the same man that was sitting on the park bench the day that the little Stilwell girl disappeared in St Kilda," she said.

About two years ago, when Percy's arrest photo was again published, identifying him as a suspect in a series of unsolved murders, the witness came forward again. "I am absolutely sure that the man I saw sitting on the park bench the day Stilwell disappeared is the same man," she said.

When Percy was asked by his policeman friend about Linda's disappearance, he said that he had driven through St Kilda that day. Asked if he was the killer, he said: "Possibly, I don't remember a thing about it."

In his belongings police found maps he had marked. One was in West Ryde near where the Wanda Beach victims caught the train, one was marked through Glebe where Simon Brook was killed, and another was marked with a line past the spot where Linda Stilwell was last seen.

Victoria's State Coroner Graeme Johnstone is expected to hold an inquest into her disappearance. Whenever Linda Stilwell's mother, Jean Priest, moved house, she would go to the homicide squad to pass on her new address in the hope that one day she would get the call that there had been a breakthrough. But over the years she found the new generation of detectives no longer even recognised her daughter's name.

Operation Heats has given her new hope. "It has helped me to know that people like (Senior Detective) Wayne Newman have cared so much and done so much work," she said last week. "You learn to live with what has happened but you can never forget."

All she wants now is for the evidence against Percy to be produced at inquest. "Then I will be able to put a name to the face … I just hope he would finally admit what he has done."

Derek Percy was surprisingly chatty when Operations Heats investigators questioned him in early 2005. Balding with a long grey beard, he has retained his striking cold blue-eyed stare. He chatted happily while drinking tea with three sugars and nibbling on a cheese and tomato sandwich.

He is serving an indefinite sentence under the insanity verdict, but he has previously applied for a minimum term — an appeal that has failed because he is considered a danger to the community.

He still hopes to be released, and a confession that he had killed many times would destroy that dream. Having received a navy pension since his arrest, he is one of the richest inmates in prison, with nearly $200,000 in the bank.

Detectives were to ask him 1535 questions. He could recall details of his childhood but when asked about the murders he grew quiet.

NSW Detective Sergeant Adam Barwick said that when Percy was asked about the Brook murder he was "visibly different, in that his lip quivered, and his answer was 'I can't remember'. I formed the opinion that Percy was lying when answering these questions."

Police believe that Percy's claim that he cannot remember is self-protection rather than self-deception. They think he is bad — not mad.

Ironically, detectives say, the charade that he was insane at the time of the crimes is in the public interest. If he had stood trial and been convicted in 1970 for the murder of Yvonne Tuohy he would have been released years ago … and would inevitably have struck again.

THE LIFE AND CRIMES OF DEREK PERCY

It also raises allegations which link the disappearance of the Beaumont children to the abduction of other children almost four decades ago.

Major Crime police have dismissed the claims in convicted paedophile Mark Trevor Marshall's 40-page hand-written document, saying they are his "sexual fantasies" and similar to material he has produced over the past four years.

Marshall, left, was, in 2009, jailed until further order by Justice Margaret Nyland, having been to prison at least six times since 1987 for sexual assaults on children.

Justice Nyland said he was "incapable of controlling his sexual instincts" but she then overturned her order.

Detective Senior Sergeant Paul Lewandowski of the Sexual Crimes Investigations Branch said the document by Marshall, which was submitted to the Mullighan Inquiry into abuse of children in state care in 2007, would be reviewed after The Advertiser passed it on to police.

However, police said that they would not investigate the claims further, having previously checked their validity.

In the document, Marshall writes graphic accounts of his involvement and presence as a young child at the River Torrens drowning of Adelaide University Professor George Duncan in 1972.

It also puts the young Marshall at the scene of the murder of girls Joanne Ratcliffe and Kirste Gordon, who were abducted from Adelaide Oval on August 25, 1973.

And it links his grandfather to the disappearance of the Beaumont children in 1966 and a string of sexual assaults.

It also outlines, with hand drawn maps and descriptions, where he believes the bodies of children he claims were murdered by his grandfather were buried.

Marshall's confession was anonymously sent to The Advertiser. The prison fellowship volunteer who sent it to Mr Mullighan has quit as an in-prison counsellor but is believed to still meet with Marshall. Efforts to contact him have been unsuccessful.

Fifty-four years ago Australia lost its innocence with the kidnapping of the Beaumont children – now we may know what happened.

Fifty-four years ago today, Australia lost its innocence, on what was meant to be a day of celebration.

Jane, Arnna, and Grant Beaumont, aged nine, seven and four, respectively, were lured from Glenelg Beach in Adelaide by an unknown assailant.

Like they had many times before, they caught the bus to the beach unsupervised, with sensible Jane Beaumont tasked with ensuring the younger children’s safety.

Such an arrangement may seem akin to child neglect today, but it wasn’t uncommon in 1966. The bus trip was only five minutes, Australia was regarded as a safe place to raise children, and many kids in neighbourhoods across the country enjoyed a free range upbringing.

The disappearance of the Beaumont children and the widespread coverage it received changed all that. Stranger danger was the new normal, and tight communities eyed each other nervously, former neighbours now potential suspects. The Australian way of life had forever changed.

Despite the story of the Beaumont children remaining in the country’s collective consciousness for more than half a century, the three children have never been found, and the identity of the 30-something slim man who was spotted with the children that day by numerous onlookers remains a mystery.

Two strikingly similar child abductions that occurred around the same time may be the key to solving this harrowing crime.

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

Adelaide Oval was packed for the August 25, 1973 Aussie rules match between Norwood and North Adelaide.

Joanne Ratcliffe, 11, was one of 13,000 spectators who attended the football match. She was sitting with her parents and next to Kirste Gordon, a four-year-old who was in the care of her grandmother. Joanne’s family had been to the oval to watch dozens of games, and the young girl knew her way around the grounds. Bored, she struck up a friendship with the four-year-old sitting next to her, and when the younger child asked to go to the bathroom, Joanne volunteered to take her.

The Ratcliffe family had a rule: Joanne could go to the bathroom while the game was being played but not during the last quarter, nor in any of the breaks. The two girls went together early in the game and then again during the third quarter. The second time, they did not return.

A skinny-faced man around the age of 40, wearing a brimmed hat and a tweed jacket, was spotted with the girls in and around the oval by numerous witnesses.

The assistant curator of Adelaide Oval, Ken Wohling, spotted the man and the two young girls behind the grandstand trying to coax a kitten out from under a car.

Anthony Kilmartin, 13, was selling drinks and lollies when he saw the man come from behind a tree and “scoop up” the younger girl with one arm and carry her towards the southern gates, with Joanne following frantically behind.

According to Anthony, Joanne, who he later identified from a selection of photographs, was kicking the man in the shins and pulling at his jacket. He was angrily yelling “clear off” before taking her by the arm and leading both children out the gates.

Sue Laurie, just one year older than Anthony, witnessed the same scene but mistakenly read this as a family dispute. This misinterpretation was understandable, and even after learning of the abductions, she didn’t make the link. It wasn’t until 1980, when she offhandedly mentioned the scene to her husband, that it began to weigh heavily on her mind. She reported it to police but didn’t revisit this day again in her mind until almost two decades later.

“The child was crying,” she told Adelaide radio station 5AA in 1998, “and a second girl who looked a few years younger than me was running after the man, thumping him and punching into him and shouting, ‘We want to go back’.

“I assumed, absolutely assumed, that the man must be the girls’ grandfather and that the girls were misbehaving. I watched it all for about 60 seconds, and my main reaction was surprise that the grandfather didn’t tell his granddaughter off for hitting him.”

Ninety minutes later a motorist spotted the trio some three kilometres past the oval, and such was Joanne’s distress, the man pulled over before thinking twice about interfering. This was the last reported sighting of the two girls or the man.

Given the man’s distinct appearance, and how he was acting in broad daylight, in an oval containing 13,000 people, police were able to get an accurate description.

The identikit picture was drawn and widely disseminated and an eerie connection was apparent to all.

The police sketch of the suspect in the Adelaide Oval case looked exactly the same as the one drawn years earlier after the Beaumont children went missing.

THE MACKAY MURDERS

Judith and Susan Mackay, aged seven and five, were only 200 metres from their house in Townsville when they were abducted. They had only left home 10 minutes earlier, strolling up to the bus stop to head to school.

Their naked bodies were discovered two days later in a dry creek bed. Both girls had been raped, and each had been stabbed three times in the chest. Both of them were choked to death before the sexual assaults took place: Susan with the killer’s bare hands, and Judith after sand was forced into her mouth and nose, blocking her airways.

With chilling precision, their school uniforms were neatly folded and placed beside them, along with their straw hats and school bags. Even their socks were folded and placed carefully, one inside each little shoe.

As with the Adelaide Oval case and the Beaumont children disappearance, there were plenty of witnesses. One man saw a slender male leaning out of a car, talking to the girls at the bus stop, at 8.10am. Three hours later, and 85 kilometres away, the same man pulled up at a service station and refuelled. The attendant, Jean Thwaite, recalled later that one of the two girls with the man asked, “When are you taking us to mummy? You promised to take us to mummy.” The two children seemed upset.

Later still, another driver had a heated argument with the man, who was with two young girls in school uniforms that matched those of the Mackay girls.

Although these latter two sightings were the most concrete, they were disregarded by police, as both the petrol station attendant and motorist claimed the car was a Vauxhall with a mismatched driver’s side door. They also both gave similar descriptions of a man with a narrow, long head and high cheekbones.

Police were told by numerous other witnesses, however, that the car was an FJ Holden with a mismatched door, and given this description happened to match a car parked near where the bodies were found, police focused on finding this vehicle above all else. A police sketch was never circulated to media, as the car was thought to be the salient piece of information.

The FJ Holden was never located, vital witness statements were not treated seriously, and the case quickly went cold.

Eighteen years later, while watching a TV report on the case, Sue Laurie sat up with a start. She recognised the man who was being charged with the Mackay murders. It was the same man she had seen a quarter of a century earlier, the “grandfather” who was being hit by a distressed young girl as he steered two children out of Adelaide Oval.

ARTHUR STANLEY BROWN

On July 6, 2002, Arthur Stanley Brown slipped away for the final time, aged 90. He died alone, in a nursing home in Malanda, Queensland. He left no blood relatives and gave instructions to his carer that there were to be no death notices published. It took months for the media to report on his death.

Brown died an innocent man, having never been convicted of any of the crimes he was charged with, including the rape of six children, the Mackay murder and 45 sexual assault charges.

Photos of him taken in the 1970s and in his later life look shockingly similar to the identikit police sketches from the Adelaide Oval murders. His appearance remained consistent throughout his adult life, giving witness sightings from decades ago a vivid quality.

From all accounts, Brown was a very strange man. He was meticulously neat to a fault, with immaculately pressed shirts, and an odd habit of folding garbage up into near squares before disposing of it. This latter quality interested police, given the neatly folded clothing near the Mackay sisters’ bodies. He also drove a Vauxhall with an oddly coloured door, which he replaced and buried shortly after the murders as he didn’t want “anyone interviewing or annoying him”.

Brown married Hester Porter in 1944 and became stepfather to her three children while also conducting an affair with Hester’s sister Charlotte. When Hester died in 1978 following a fall, he quickly married Charlotte. Charlotte’s son, Peter Neilsen, believes Brown actually killed his first wife, fearing she was planning to go to the police.

Hester had caught Brown molesting a child and confessed to her older sister Milly that she made sure he was never alone with her children. It wasn’t enough to protect them.

As various relatives came forward in the early 1980s and claimed that Brown had molested them as children, they teamed up and sought legal advice. Sadly, they were advised to keep this a family secret for fear that a trial may be traumatic for Brown’s many victims. Many of the children were taken by Brown to the same dry creek bed the Mackay sisters were found in.

Brown lived in Queensland all his life and repeatedly denied he was in Adelaide around the time of the Ratcliffe/Gordon disappearance. He once betrayed this in a conversation with Mim Moss, a relative through marriage. Brown was talking to Moss and her sister, who had just returned from Adelaide. He mentioned he visited Festival Hall not long after it opened – which would place him in the area in 1973.

Moss also claimed Brown was obsessed with the Mackay sisters’ killings, as he worked as a carpenter at their school.

“He asked aunty Hester, my sister and I if we wanted to go out and see where the Mackay girls were murdered,” Ms Moss said.

“It would have only been a couple of weeks after they were found.’’

Brown also had a secret room in his house that locked on the inside.

“Aunty Hester and I got in there one day and found bottles of port wine and all these books, true stories on women who had been murdered, absolutely slaughtered,” she said.

“He used to get all the grandkids drunk and show them the pictures of women who had been gutted and say, ‘Look, isn’t that wonderful?’ There was paraphernalia like ropes and stuff like that.’’

BROWN CHARGED BUT NOT CONVICTED

A 1998 crime special led to Brown’s arrest. The program focused on the 1970 murder of the Mackay sisters and prompted one of Hester’s cousins, who was molested by Brown and long suspected him of the murders, to call Crimestoppers.

She reported that Brown had molested several of his relatives and shared her suspicions of the Mackay murders. Police cast a wide net and located two men who claimed Brown confessed to the murders, although neither took him seriously at the time.

The motorist who argued with the man on the day of the Mackay abduction and the petrol station attendant who saw the upset girls in his car both positively identified Brown as the man they saw in 1970.

The evidence against Brown was circumstantial, and a Supreme Court jury was unable to decide upon a verdict.

A retrial was scheduled, but Brown’s wife Charlotte fronted the Mental Health Tribunal and claimed that he was unfit to stand trial due to his increasing dementia. Brown was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and the prosecution dropped the charges, believing it pointless to continue.

Arthur Stanley Brown died in 2002, with a clean criminal record. Members of his own family believe he may have been responsible for at least nine murders.

The Mackay case is officially closed, with police satisfied that Brown was the killer, but both the Adelaide Oval abductions and the location of the Beaumont children remain a mystery.