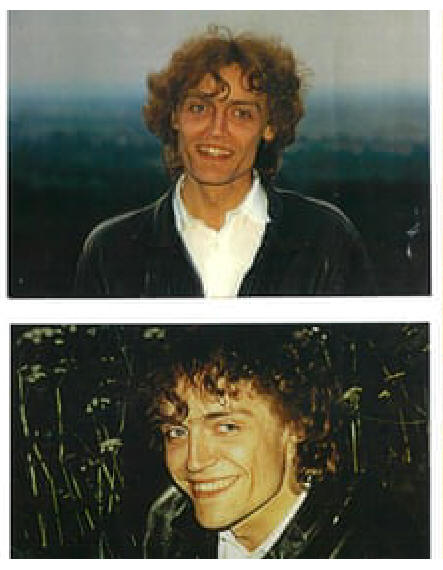

Peter Karl BAUMANN

aka “Peter Moltzen” and “Peter Ann”

| DOB: | 1957 German National |

| HAIR: | Fair | BUILD: | Medium 183cm tall | EYES: | Green/Hazel |

| CIRCUMSTANCES: | |||||

| Peter Baumann was last seen at Waverley, Sydney in October 1983. He spoke to a friend on the telephone and during the conversation, the call was terminated. A check of the premises was made and as a result, it appeared that he had left in a hurry, taking no clothes or money with him. Peter has not been heard from since. There are grave fears for his safety. He had arrived in this country from Germany in 1981. | |||||

Special Commission of Inquiry into LGBTIQ hate crimes

SUBMISSIONS OF COUNSEL ASSISTING 1

27 June 2023

IN THE MATTER OF PETER KARL BAUMANN

Introduction

1. These submissions are filed on behalf of Counsel Assisting the Special Commission of Inquiry into LGBTIQ hate crimes (Inquiry).

2. The death of Peter Baumann has been determined to fall within ‘Category B’ of the Inquiry’s terms of reference. That is, Mr Baumann’s death is an unsolved suspected hate crime death in NSW that occurred between 1970 and 2010, where the victim was (or was perceived to be) a member of the LGBTIQ community and the death was the subject of a previous investigation by the NSW Police Force (NSWPF). Summary of matter Date and location of death

3. Mr Baumann is recorded in a coronial finding as having died on or sometime after 26 October 1983. 1 Although that finding was consistent with material provided to the coroner, there is some doubt about the date Mr Baumann was last seen, as discussed below.

4. On 29 November 1983, a missing persons report was prepared by the NSWPF, recording a report by Mr Baumann’s landlady, Ruth Binney. 2 However, there is evidence that the NSWPF were notified of Mr Baumann’s disappearance as early as 5 November 1983. 3 Mr Baumann was 25 years old at the time of his disappearance. On 4 August 2009, Deputy State Coroner Milovanovich found that Mr Baumann was deceased, but was unable to determine a precise date, place, or manner and cause of his death.4

Circumstances of death

5. Mr Baumann’s last known contact was either with his ex-partner, Sharmalie Seneviratne (now Sharmalie Kotoga) or with another partner, Allan Smyth. 5 Given that the police investigative file uses the name “Seneviratne”, Ms Kotoga will be referred to as Ms Seneviratne in these submissions for convenience.

6. According to Ms Seneviratne, she spoke with Mr Baumann by telephone at his home on “one Friday” evening. During that conversation, “the telephone went dead in his mid sentence”. Ms Seneviratne tried to ring Mr Baumann back “a number of times but the line was dead”. Ms Seneviratne was worried something had happened to Mr Baumann, so she drove to his home and went inside. She noted that Mr Baumann’s house was “very untidy” and it “looked as though there had been a struggle in the room”. She also noticed that a small cushion had been burnt in the shower recess.

7. Ms Seneviratne later telephoned Ms Binney who went to Mr Baumann’s flat to find “the chair overturned and the door open… and his bed pillow was lying in the shower half burnt”. 9 Later, after reporting the incident to Waverley police, while looking through Mr Baumann’s room, Ms Binney “saw that the word ‘AIDS’ had been written on a mirror”. 10 There is evidence to suggest that Ms Seneviratne saw (or knew about) the fact that ‘AIDS’ was written on a mirror in the flat “with chalk or felt-tip pen” but also conflicting evidence suggesting that Ms Seneviratne did not know about this.

8. The date that Mr Baumann was “last seen” was recorded by the NSWPF to be on or around 26 October 1983. However, the evidence available about Mr Baumann’s last known movements suggests that he was seen after that date. This evidence includes:

a. Mr Baumann was recorded as having “walked off duty at about 11:30am on Thursday 27th October” at his place of employment, the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC), as it then was.

b. Ms Seneviratne provided a statement to NSWPF in 1993 where, as noted above,she stated that the last time she spoke to Mr Baumann was a Friday, meaning that she likely spoke to him on 28 October 1983 (although it is possible that it was 21 October or conceivably 4 November).

c. A statement given by Mr Smyth in 1993, whom Mr Baumann was in a relationship with at the time of his disappearance, might be construed as indicating that Mr Baumann was seen as late as Sunday 30 October 1983, or even the following Sunday 6 November 1983.

d. Although some police documentation refers to Mr Baumann as having disappeared on 26 October 1983, other police documentation refers to 27 October 1983 as the relevant date, including documentation prepared closer to the date of Mr Baumann’s disappearance.

9. The evidence surrounding Mr Baumann’s disappearance is discussed further below. However, what is clear is that Mr Baumann has not been seen since late October/November 1983 and his remains have never been found.

Findings of post-mortem examination

10. Mr Baumann’s body has never been found and as such a post-mortem examination has never been conducted.

Persons of interest

11. Although there is no evidence before this Inquiry to indicate that the NSWPF investigated Mr Baumann’s disappearance in its immediate aftermath, in subsequent years, police have spoken to a select number of witnesses which included friends, intimate partners, and acquaintances of Mr Baumann. No persons of interest were identified in relation to his death.

12. Given the passage of time as well as the death or infirmity of certain key witnesses, there is no cogent evidence beyond what is outlined below to suggest that any identifiable person had any involvement in Mr Baumann’s death. Indicators of LGBTIQ status or bias

13. Mr Baumann was a gay or bisexual man. At the time of his disappearance, Mr Baumann was in a relationship with another man, Mr Smyth. It appears that Mr Smyth was also in a long-term relationship with another man called Mervyn Oliver Keasberry (who went by ‘Oliver’) at the same time, although that relationship may not have been sexual. Mr Smyth and Mr Keasberry lived together in Edgecliff, Sydney.

14. Mr Baumann had at least two relationships with women. In June 1982, Mr Baumann married Cherie Foster. There is evidence to suggest that this marriage was arranged so that Mr Baumann, who was a German national, could get permanent residency in Australia. On 29 April 1983, Mr Baumann was granted permanent residency in Australia. Mr Baumann and Ms Foster filed for divorce in or around June or July 1983. Mr Baumann had also previously been in a relationship with Ms Seneviratne. Mr Baumann met Ms Seneviratne in December 1981 when Ms Seneviratne was working in Colonnade Gift Shop in Sydney. In or around early 1982, Mr Baumann asked Ms Seneviratne to marry him, but she refused. According to Ms Seneviratne, she “was only seventeen or eighteen at the time” and she “was also a bit suspicious that he might be using the marriage to gain permanent residency in Australia”. Some time before July 1982, Ms Seneviratne ended the relationship.

15. The circumstances of and motivation for Mr Baumann’s disappearance and suspected death are unclear. Given that Mr Baumann disappeared in suspicious circumstances and that Ms Binney saw the word ‘AIDS’ written on a mirror in Mr Baumann’s flat, there is a reasonable and objective basis to suspect homicide with a hate/bias motive. Ms Seneviratne also told Mr Baumann’s brother and sister that the word ‘AIDS’ was written on a mirror in Mr Baumann’s flat with “chalk or felt-tip pen”. 25 However, this fact is not contained in the statement she provided to police and conflicts with other (indirect, hearsay) evidence provided to the Inquiry. 26 It may have been that Ms Seneviratne was passing on information she had learned from the police or Ms Binney. The evidence available to this Inquiry does not allow any positive conclusions to be drawn about whether Mr Baumann’s death was occasioned as a result of an LGBTIQ hate/bias crime. It is also important to bear in mind that bias on the basis of sexuality and on the basis of HIV-status are distinct, although they may overlap, especially given social perceptions and attitudes to homosexuality at the time of Mr Baumann’s disappearance.

Exhibits: availability and testing

16. Following Mr Baumann’s disappearance, Ms Binney kept a “long knife” found in Mr Baumann’s jacket pocket and his guitar. Police subsequently seized these items, but they were never the subject of any forensic examination. In 1994, these items were returned to Mr Baumann’s family.

Findings at inquest, including as to manner and cause of death

17. On 4 August 2009, an inquest was conducted by Deputy State Coroner Milovanovich. That same day, his Honour made the following finding in relation to Mr Baumann: I am satisfied that Peter Karl Baumann is deceased. I find that he died some time on or after the 26th October, 1983. As to the precise date of death, place of death or manner and cause of death from the available evidence I am unable to say.

Criminal proceedings

18. No criminal proceedings were ever instituted against any person in relation to Mr Baumann’s disappearance or death.

Features of /concerns with original police investigation

19. The aspect of the original NSWPF investigation into Mr Baumann’s disappearance that is most concerning is the absence of any such investigation; there are no records of any investigation being conducted by the NSWPF into Mr Baumann’s disappearance in 1983. Indeed, based on the material produced to this Inquiry it appears that a period of nine years elapsed from when Mr Baumann was reported missing to the time that the NSWPF took any substantive investigative steps in relation to his disappearance.

20. The missing person’s report by Ms Binney was apparently prepared on 29 November 1983. However, and as noted above, a contemporaneous file note indicates that the NSWPF were made aware of Mr Baumann’s disappearance by 5 November 1983, when the Acting Welfare Officer at the ABC, “H.A.R. Gover”, notified Waverley Police Station that he hadn’t been seen or contacted the ABC since 27 October 1983, and that Mr Gover had been unable to find him. 32 Ms Binney’s evidence is also consistent with Ms Binney notifying the police much earlier in November than 29 November 1983.

21. Another NSWPF document indicates that Mr Baumann was reported missing on 27 October 1983, although given this document was prepared in 2016 it is submitted that the contemporaneous documentation should be preferred as the likely date or dates the NSWPF were notified about Mr Baumann’s disappearance.

22. At some stage following the receipt of the report of Mr Baumann’s disappearance, police officers from Waverley Police Station attended Mr Baumann’s residence, apparently with Ms Binney. A note was made or a photograph taken of Mr Baumann’s identity card or passport details (the evidence is not perfectly clear which), but no other investigative steps appear to have been taken.34 Ms Binney in her 1993 statement said she kept Mr Baumann’s clothes, personal possessions and papers at her house until 1992, when they were destroyed as they were rotting. According to Ms Seneviratne in her statement in 1993, Ms Binney said that the police had taken his passport, wallet and personal papers, but as second hand hearsay this evidence is not reliable and Ms Binney’s first hand account is more reliable.

23. It was not until between 1992 and 1994 that an investigation into Mr Baumann’s disappearance was conducted by the NSWPF Missing Persons Unit (MPU). This investigation appears to have been triggered by an inquiry made by Ms Seneviratne to the MPU. The NSWPF then undertook various investigative steps which are discussed further below. However, even these investigative steps were limited in their scope.

24. The failure to properly investigate Mr Baumann’s disappearance in 1983 created a situation where it was much more difficult, even by 1992, for subsequent investigators and other finders of fact to establish the manner and cause of Mr Baumann’s death.

Steps which could / should have been taken, but which were not

25. It is submitted that there are several key steps that could or should have been taken in this case but were not.

26. First, and obviously enough, the NSWPF should have conducted a proper investigation into Mr Baumann’s disappearance in the immediate aftermath of receiving the missing persons report. Such an investigation should have entailed establishing a crime scene, taking photographs, and identifying and retaining any physical exhibits of forensic value. Furthermore, to the extent that the police did conduct enquiries in relation to Mr Baumann’s disappearance (such as attending the Cross Street premises and obtaining information about Mr Baumann), no record of any such enquiries have been produced to this Inquiry.

27. If Ms Binney’s recollection in 1993 is reliable, police attended the unit where they should have observed ‘AIDS’ written on a mirror. There were other grounds for suspicion as to Mr Baumann’s absence, including the room being in disarray, a burnt pillow in the shower, and all Mr Baumann’s personal effects apparently being left. By 29 November 1983, it appears both Mr Gover and Ms Binney had notified police. As explained below, Mr Gover had also received a telephone call from “ Sharmalee” (presumably Ms Seneviratne)37 and “William” who lived at “Artell (?) St Edgecliff”. 38 Simple inquiries in November/December 1983 would likely have identified each of Ms Seneviratne, Mr Smyth and Mr Keasberry as persons who may have information about Mr Baumann’s disappearance. At least by 1993, Ms Binney appears to have come to believe or suspect that Mr Baumann’s disappearance was “a murder involving homosexuals”, 39 although it is not presently known whether Ms Binney suspected this in 1983.

28. The Inquiry cannot draw any affirmative conclusion as to whether the failure to investigate further was actuated by bias, but it is a real possibility given

(a) what was known or readily ascertainable to police, including ‘AIDS’ written on the mirror, and

(b) the widespread bias in the police force and the wider community at the time. Even if the failure to investigate was not motivated by bias, there was enough information available to suggest that Mr Baumann’s disappearance was suspicious, calling for immediate investigation. The earliest written policy or procedure produced to the Inquiry by the NSWPF in relation to missing persons is dated 1985. 40 Accordingly, it is not known whether the failure was a breach of any applicable policy or procedure, but it would be open to the Inquiry to conclude, in the absence of other evidence, that the apparent failure to investigate was a material oversight or deficiency in the NSWPF response to Mr Baumann’s disappearance.

29. Second, the NSWPF should have sought to speak with Mr Baumann’s associates as soon as practicable after Mr Baumann disappeared. There are some inconsistencies in the evidence provided by some of the witnesses to Mr Baumann’s disappearance, and the details around particular events are vague, if not dubious. Based on the documents produced to this Inquiry, the NSWPF did not take any steps to test the veracity of the accounts provided to them by various witnesses, even when they conflicted. There were also a number of investigative leads, generated by the information provided by these witnesses, that were also never tested, either in 1983 or in the investigatory steps taken in 1992 to 1994. For example, the NSWPF never made further enquiries about the “protectors” of Ms Foster who were allegedly threatening Mr Baumann, and nor did the police seek to interview Mr Keasberry. Some of the inconsistencies and evidence raising lines of inquiry that were not pursued is canvassed further below.

30. It cannot be inferred that by the time the police investigated Mr Baumann’s disappearance they had spoken to all his friends and acquaintances. For example, it is likely police would have been able to locate and speak to Mr Baumann’s neighbour, Hiroshi Hamasaki, who they were subsequently unable to locate. There is also no evidence that the NSWPF spoke to any of Mr Baumann’s colleagues at the ABC. This may have opened further lines of inquiry.

31. The failure to establish a crime scene and/or identify or retain any exhibits of forensic value , and the failure to identify and locate relevant witnesses, has limited the ability of subsequent investigators and other finders of fact to establish the manner and cause of Mr Baumann’s death. With the passage of time, the ability to identify and obtain evidence from any relevant witnesses has greatly diminished. In this case, it is understandable that the ability of the witnesses a decade later to identify the dates and/or times on which specific events took place has been compromised by the passage of time. Indeed, when the police contacted Mr Gover in 1994, he appeared to have no recollection of Mr Baumann’s disappearance at all.41 Likewise, the failure to identify and retain exhibits means that it is not possible to utilise developments in forensic science to collect additional evidence that could assist with resolving the question of the manner and cause of Mr Baumann’s death.

32. Third, and to the extent that the NSWPF did conduct an investigation into Mr Baumann’s disappearance, it should have ensured that its understanding of events was as accurate as possible, particularly in relation to understanding the chronology around Mr Baumann’s disappearance. It some of the NSWPF documentation, particularly those produced in more recent years, little regard appears to have been paid to contemporaneous documentation and there is a lack of precision in relation to the date that Mr Baumann was thought to have disappeared. It is submitted that investigations, particularly when a long period of time has elapsed between the relevant event/s and the investigation, need to be mindful of the unreliability of reconstructions based on a recollection many years later, and the primacy of whatever objective contemporaneous records can be obtained.

33. In addition, there is evidence to suggest that by June 1994, there was tension between Senior Constable (SC) Gribble and Senior Constable (SC) Emery about the NSWPF response to Mr Baumann’s disappearance, including about the fact that it had apparently taken over 10 years to notify Mr Baumann’s family that he had been reported missing. 43 SC Gribble appears to have been frustrated or angry that not enough was being done in relation to this particular case, with SC Emery informing him that “Waverly Dets were satisfied that all avenues of inquiry have been exhausted and Waverly Dets would not make any further inquiries”. 44 Elsewhere, at the same time, SC Emery noted that “every attempt to locate Peter Baumann” had been made.45 In this respect it is both notable and laudable that SC Gribble continued to agitate for this case to be reinvestigated as recently as 2016.46 It is submitted that the failure of the NSWPF to identify the fact that there were still several significant avenues of inquiry available to them, including as at 1994, was a material oversight or deficiency in the police investigation.

Later UHT reviews

34. The Inquiry has been provided with an undated form entitled “Annexure A Triage Form Review of an Unsolved Homicide” which purports to be a triage assessment of Mr Baumann’s case by the Unsolved Homicide Team (UHT)

35. This form appears to be incomplete, and it has not been signed. Nonetheless, to the extent that the form has been populated, it is curious that it states that a post-mortem was conducted by a “Dr Paul Botterill” and that the cause of death was determined to be “[h]omicidal violence of undetermined aetiology”. 48 In circumstances where Mr Baumann’s remains have never been recovered (and therefore no post-mortem has been able to be performed) it can be assumed this entry relates to another case.

36. On 13 April 2017, Detective Inspector (DI) Leggat from the UHT finalised an ‘Issue Paper’ in response to a request from SC Gribble and dated 21 November 2016 to conduct a further investigation into the disappearance of Mr Baumann. DI Leggat concluded that the UHT should not conduct an investigation into Mr Baumann’s disappearance. DI Leggat wrote that: The matter has been adequately investigated by the Eastern Suburbs LAC and in the absence of fresh information a further investigation by the Unsolved Homicide Team is not warranted. 49

37. DI Leggat ultimately recommended that the investigation remain with Eastern Suburbs LAC to finalise the outstanding issues identified by SC Gribble in his correspondence to the UHT that had not already been performed by other police officers.

Investigative and other steps undertaken by the Inquiry

38. In the course of investigating Mr Baumann’s case, the Inquiry took a number of investigative and other steps. These included:

a. requesting the coronial file; and

b. issuing a summons for the police investigative file.

39. The Inquiry reviewed and analysed a considerable volume of material provided by NSWPF and the Coroners Court, and the material obtained by summons, and considered whether any further investigative steps or other avenues were warranted. These investigative steps included:

a. issuing summonses to the NSW Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages (BDM) and the equivalent agency in Western Australia to obtain information about key witnesses;

b. issuing summonses to New South Wales Health (NSW Health) and St Vincent’s Hospital (St Vincent’s) to obtain any medical records relating to Mr Baumann;

c. requesting information from Services Australia in relation to Mr Baumann;

d. contacting key witnesses;

e. contacting the Forensic and Analytical Science Service (FASS) as to requesting that the DNA profiles of Mr Baumann’s relatives be run against all unidentified bodies in New South Wales; and

f. contacting Mr Baumann’s family.

Request for coronial file

40. On 15 June 2022, the Inquiry issued a written request to the Registrar of the Coroners Court of NSW at Lidcombe to obtain the coronial file in relation to the death of Mr Baumann. The Coroners Court answered the request and provided the coronial file on 1 August 2022.

Summonses and requests issued to NSWPF

41. A summons to the NSWPF (NSWPF3) was issued on 21 July 2022 for, inter alia, all documents in relation to the investigations by NSWPF into the death of Mr Baumann, and any other material held by the UHT in relation to Mr Baumann’s death. Material in relation to Mr Baumann was provided to the Inquiry in two tranches on 9 and 12 August 2022, respectively. 52 A further tranche of material was provided to the Inquiry on 22 June 2023, which consisted of 401 pages of documents.

42. On 31 January 2023, a letter was sent to the NSWPF seeking further information about the production of documents which indicated that the Northern Territory Police Force (NTPF) notified NSWPF MPU of an unidentified body that they believed might have been Mr Baumann and seeking to compare the DNA profile obtained from Mr Baumann’s mother with the unidentified body

43. On 6 and 21 March, the NSWPF informed the Inquiry that the DNA comparison that was conducted does not support the conclusion that the unidentified remains were those of Mr Baumann.

44. On 5 June 2023, a summons to the NSWPF (summons NSWPF119) was issued seeking intelligence material in relation to various witnesses. That material was produced on 8 June 2023.

Other summonses issued

45. On 21 December 2022, the Inquiry issued a summons to the Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages (BDM) for records of, inter alia, Mr Baumann (summons BDM8). On 22 December 2022, BDM produced these records to the Inquiry.

46. On 21 December 2022, the Inquiry issued a summons to NSW Health to obtain any medical records relating to Mr Baumann, including in relation to any HIV/AIDS diagnosis (summons NSWH1). 56 On 11 January 2023, NSW Health advised that it held no records to responsive to the summons. NSW Health further advised that HIV/AIDS became a “notifiable condition” in NSW in 1984 and suggested that the Inquiry approach St Vincent’s Hospital (St Vincent’s) in relation to any HIV/AIDS diagnoses made between 1982 and 26 October 1993.

47. On 10 March 2023, the Inquiry issued a summons to St Vincent’s to obtain any medical records relating to Mr Baumann (summons SVH2). 58 On 15 March 2023, St Vincent’s advised that it held no records responsive to the summons and that it was unable to be of any further assistance. 59

48. On 10 March 2023 and 19 June 2023, further summonses were issued to the Western Australia Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, for the records of various witnesses (summonses WBDM4 and WBDM6). These records were produced on 16 March 2023 and 20 June 2023 respectively. Those records include a death certificate which records that Mr Smyth died on 6 October 2016, aged 96 years.60 There is evidence before the Inquiry which suggests that Mr Smyth’s memory was failing him as early as 2007, due to his age.

49. On 1 June 2023, a summons was issued to the Western Australia Police Force seeking records in relation to various witnesses (summons WAP3). Those records were produced in two tranches, on 7 June 2023 and 19 June 2023 respectively.

Attempts to locate and contact family members

50. On 19 June 2023, the Inquiry sent a letter to Mr Baumann’s sister, Anna-Christa Baumann-Serr, requesting any information she may hold in relation to Mr Baumann’s death. On 22 June 2023, the Inquiry was contacted by Ms Baumann-Serr.

Other sources of information

51. On 22 December 2022, a letter was sent to Services Australia regarding any Medicare and PBS records that were in existence in relation to Mr Baumann.63 On 17 January 2023, the Inquiry received a response from Services Australia confirming that there were no such records available.

52. On 13 March 2023, a letter was sent to Ms Binney, inviting her to meet with the Inquiry to discuss the circumstances surrounding Mr Baumann’s disappearance. On 14 April 2023, Ms Binney contacted the Inquiry, advising that she was not in a position to provide any further information relating to Mr Baumann’s disappearance.65

53. On 13 March 2023, a letter was sent a letter to Ms Seneviratne inviting her to meet with the Inquiry to discuss the circumstances surrounding Mr Baumann’s disappearance. On 5 June 2023, Ms Seneviratne contacted the Inquiry, advising that she was not in a position to provide any further information relating to Mr Baumann’s disappearance.

54. On 5 June 2023, a letter was sent to Ms Foster, inviting her to meet with the Inquiry to discuss the circumstances surrounding Mr Baumann’s disappearance.67 The Inquiry did not receive a response from Ms Foster.

55. On 5 June 2023, a letter was sent to FASS seeking confirmation that it held the DNA profiles for Mr Baumann’s mother and father, and requesting that, if so, the DNA profiles of Mr Baumann’s parents be run against all unidentified bodies in New South Wales.68 On 20 June 2023, Carole Field, Group Manager of the Database and Case Management Unit at FASS, provided the Inquiry with a statement detailing FASS’ response to the Inquiry’s queries. 69 Ms Field stated that FASS did not hold a reference sample for either of Mr Baumann’s parents but that the NSWPF had received a mitochondrial DNA report in relation to Mr Baumann’s mother and her mitochondrial DNA profile could be used to search against all mitochondrial DNA profiles from unidentified human remains on the national DNA database. However, Ms Field stated that to date, no mitochondrial DNA match has been identified.

Other steps

56. On 20 June 2023 the Inquiry arranged for a search to be conducted on the National Coronial Information System (NCIS) for any further information related to Mr Baumann's disappearance. No relevant results were obtained.70

57. The Inquiry also took certain steps by way of private hearing, which will be the subject of a confidential part of the Report of the Inquiry in due course.

Submissions as to the evidence now available

58. This section of the submission sets out key matters arising from the Inquiry’s consideration of the evidence and the conclusions that it is suggested can be drawn from the evidence.

Background and disappearance

Arrival in Australia

59. Mr Baumann was a German national who arrived in Sydney on 11 December 1981 on a temporary visa that was valid until 11 June 1982.

60. There is some evidence to suggest that Mr Baumann travelled to Australia for the purpose of pursuing a music career as a composer.72 After arriving in Australia, Mr Baumann may have worked as a musician at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, although the NSWPF never confirmed this. 73 At the time of his disappearance, Mr Baumann was employed by the ABC as an Assistant Sound Librarian. When he was initially employed by the ABC, Mr Baumann utilised the surname “Moltzen”.

Living arrangements

61. Upon his arrival in Australia, it appears that Mr Baumann resided at a property in Bennett Street, Bondi, but the NSWPF never confirmed this.

62. From around March 1982 to July 1982, NSWPF records indicate that Mr Baumann resided at Glebe Point Road, Glebe, with a person named Keith Smith. However, the nature of Mr Baumann’s relationship with Mr Smith is not clear; he was never spoken to by the NSWPF.

63. On or around late 1982 to early 1983, Mr Baumann moved to Cross Street, Waverley (now in Bronte) which was owned by Ms Binney.77 At the time of Mr Baumann’s disappearance Ms Binney’s name was Ruth Van Duyn (although she was still referred to by Mr Gover in his contemporaneous note as “Mrs Binney”). By the time she provided a statement to the NSWPF, her name was changed to Ruth Binney. Mr Baumann was living at this address until he disappeared in around October 1983.

64. Ms Binney would collect the rent from Mr Baumann on a fortnightly basis and, in accordance with a request from Mr Baumann, Ms Binney provided rent receipts in the name of “Peter K.J Ann”. 78

65. The Cross Street premises was a house that had been converted into five flats. At the time of Mr Baumann’s disappearance, only one other flat was occupied and the occupant was a Japanese cartoonist whose name was initially believed to be ‘Hyuma Hoshi’ but was later revealed to be Hiroshi Hamasaki.79 Mr Hamasaki was never spoken to by the police.

Relationship with Ms Seneviratne

66. According to a statement that Ms Seneviratne gave to the NSWPF in 1993, Mr Baumann first approached Ms Seneviratne in around December 1981 whilst she was working in a gift shop in Sydney. Ms Seneviratne states that she initially refused to go out with him until around January 1982, when they eventually struck up a relationship. He told her that he was a musician at the Conservatorium of Music, and they met for lunch on most days outside the Conservatorium. 80 Their relationship lasted until around July 1982 and she went to his flat at Bennett St, Bondi, on a number of occasions during that period.

67. In her 1993 statement, Ms Seneviratne stated that Mr Baumann seemed generally stable but at times could be aggressive, very demanding and possessive of her. She was prevented from talking to friends or having a social life outside of their relationship. 82 Around three months into their relationship, Ms Seneviratne stated that Mr Baumann asked her to marry him, that he had all of the relevant forms on hand, and that all she needed to do was “fill our [her] section”. Ms Seneviratne said she rejected Mr Baumann’s proposal on the basis that she was young and that she also harboured suspicions that he may be using the marriage to gain permanent residency. Mr Baumann was “very upset” with Ms Seneviratne’s response and continued to ask her to marry him until she broke off the relationship in early 1982.83 They had limited contact after the break up until just prior to Mr Baumann’s disappearance in October 1983.

Relationship with Mr Smyth

68. Mr Smyth gave a statement to police on 16 November 1993. The copy of this statement that has been produced to the Inquiry is not signed, and refers to the fact that the signed copy is contained in the official notebook of SC Gribble. These notebooks have not been produced to the Inquiry and are, presumably, missing. The failure by the NSWPF to retain these notebooks, so as to be in a position to produce them to the Inquiry, is another material deficiency in the NSWPF record-keeping. According to Mr Smyth, he was in a relationship with Mr Baumann that commenced in December 1981/January 1982. Mr Smyth met Mr Baumann in Centennial Park in the summer of 1981 when he was walking his dogs. They would meet two to three times a week either at Mr Baumann’s home or Mr Smyth’s home in Artlett Street, Edgecliff, and the relationship continued until Mr Baumann’s disappearance.84 According to a police running sheet, Mr Smyth “used to regularly see” Mr Baumann and continually referred to him as “absolutely delightful”.

69. Mr Smyth described Mr Baumann as having an obsession about not going back to Germany and wanting to avoid being conscripted. He described this as a “real fear”. Mr Smyth recalls that one day Mr Baumann attended his home and told him that he had met “a prostitute” and offered her $20,000 to marry him. Mr Smyth alleges that at some stage after the marriage, Mr Baumann told him that some people, namely “the girl’s protectors”, had approached him and asked for a further $30,000. Mr Smyth got the impression that Mr Baumann was being blackmailed and that the threats being made were of a violent nature.85

70. During this period, Mr Smyth was living with Mr Keasberry in Artlett Street, Edgecliff, and the two men had been living together since 1971.

Marriage to Ms Foster, permanent residency, and divorce

71. In or around March 1982, Mr Baumann met Ms Foster.

72. According to the P79A Report of Death to Coroner, Ms Foster was a “prostitute… who he met in Byron Bay, so that he could obtain permanent residence in Australia”.

73. This conclusion appears to be supported by evidence that suggests that Mr Baumann wanted to remain in Australia and that he did not want to return to Germany. Mr Baumann was said to have expressed his desire to stay in Australia on a number of occasions, and that he was concerned about being conscripted in Germany.88 Whilst he was living at the Cross Street premises, Mr Baumann told Ms Binney that he was married but that he was in the process of arranging a divorce. Ms Binney told police that she thought the marriage had occurred so that Mr Baumann could stay in Australia.89 However, there is also evidence that Mr Baumann was exempt from conscription on medical grounds.

74. There is some evidence to suggest that Mr Baumann paid an amount to Ms Foster in exchange for her agreeing to marry him (but the evidence in relation t o whether this involved a lump sum payment or regular payments over the course of the marriage is conflicting).

75. According to a statement given to the police on 11 April 2007 by Ms Foster’s boyfriend over the years from about 1980 to 1987, John Pauperis, Ms Foster had told him she was a “prostitute”, but she did not go into details and that as far as he knew, she did not have a pimp. Mr Pauperis attended Mr Baumann’s residence on one occasion and was not aware of any money being provided by Mr Baumann to Ms Foster. 91

76. Ms Foster gave a statement to police on 14 September 1993. Her account of events was more detailed. According to Ms Foster, she had met Mr Baumann in Byron Bay whilst Ms Foster was helping some friends at the Byron Bay Markets. Mr Baumann told Ms Foster that he was looking to marry an Australian so that he could stay in the country and that he would rather die than go back to Germany. Mr Baumann indicated that he was willing to marry Ms Foster in exchange for some money. She could not recall the exact amount but said that it was not a large sum of money. Ms Foster gave Mr Baumann her contact details.

77. Ms Foster was later contacted by Mr Baumann after she had returned to Sydney. He attended her residence in Balmain where she lived with her boyfriend, Mr Pauperis, who was also present. They discussed Mr Baumann’s suggested arrangement. Ms Foster told Mr Baumann that if she married him, she would not be able to claim any welfare benefits. He offered her $70 per week which was equivalent to those benefits.

78. On 12 June 1982, Mr Baumann married Ms Foster.

79. Ms Foster attributes her decision to marry Mr Baumann to her sympathetic nature. She states that she certainly did not agree to it for the money. Rather, “the money was a consequence of the circumstance”.

80. According to Ms Foster, after the wedding, Mr Baumann stayed in touch with Ms Foster to provide her with the agreed $70 per week. In March 1983, Ms Foster moved to a new home, but Mr Baumann continued to provide her with the funds on a weekly basis. She observed that Mr Baumann had become extremely paranoid and had developed an aggressive attitude towards women. She stated that he had been slipping notes under her door and accusing her of conspiring to have him deported. She was of the view that the notes were very out of character.

81. According to Mr Smyth, as noted above, Mr Baumann had paid a lump sum to a woman that he married and at the time of his disappearance, was being “blackmailed” for additional funds. 93

82. According to Ms Foster, she and Mr Baumann filed for divorce in around June or July 1983. 94 She last saw him at around that time after she asked him for their divorce certificate.

83. On 29 April 1983, Mr Baumann was granted permanent residency.95 October 1983

84. According to a statement provided to the police by Ms Seneviratne in 1993, Mr Baumann telephoned her “one Friday” at about 7:00pm. They spoke on the telephone for around 30 to 40 minutes. She was very shocked by the call but observed that he sounded very relaxed. He told her about his job at the ABC and indicated that he wanted to meet up. They arranged to meet at the Compass Centre in Bankstown the next day.96 Ms Seneviratne stated that during her call with Mr Baumann she asked him where he was living, and he would not answer. She became suspicious that he called her out of the blue and would not disclose where he was residing.

85. Later that same evening, she looked up Mr Baumann’s details. Ms Seneviratne found Mr Baumann’s contact details in the phone book. He was listed under the name ‘“Peter K.J. Ann”, a name he had written on an audio cassette he gave her. Ms Seneviratne telephoned that number and Mr Baumann answered. Ms Seneviratne said Mr Baumann was “very angry and sounded almost scared”. During the conversation, the telephone “went dead in his mid-sentence”. Ms Seneviratne was unable to call Mr Baumann back despite a number of attempts to do so.

86. Ms Seneviratne was worried. At around 9:00pm to 9:30pm, she went to the Cross Street premises. She said she went with her cousin, Hamish Pears, although as explained below Mr Pears denied this. Ms Seneviratne said that when she arrived at the Cross Street premises, the door was open and the flat was very untidy. Clothes were scattered across the room, and there were full ashtrays and beer bottles lying around. She said it “looked as though there had been a struggle in the room” and that “a small cushion had been burnt in the shower recess”.

87. According to Ms Seneviratne, she then left the Cross Street premises, but as she did so she spotted something sticking out of the letterbox. She “just grabbed it”; observed that there was an address on the back of the letter, and then drove to that address. The address was in Artlett Street, Edgecliff, and was the home of Mr Smyth and Mr Keasberry. At about 10:30pm that evening, Ms Seneviratne drove to this address.

88. According to Ms Seneviratne, when she arrived at the Artlett Street premises, she rang a bell on the gate. A man walked through the front door and towards the gate and asked if he could help. Ms Seneviratne described him as “caucasian, five feet eight inches tall, medium build, thirtyish, balding, dressed all in black” and said he spoke with a German accent. (It should be observed that, at this time, Mr Smyth was 63 and Mr Keasberry was 32, meaning that if Ms Seneviratne spoke to either of these two persons it was likely to have been Mr Keasberry). Ms Seneviratne told the man that she was looking for Mr Baumann and sought his assistance. The man asked how she got his address and she indicated that it was on the back of the letter which she had found in Mr Baumann’s letter box. Ms Seneviratne stated that the man “then became nervous” and asked where the letter was. After Ms Seneviratne told him that the letter was in the the letter box, the man said that Mr Baumann “should be at home”. The man then told Ms Seneviratne that he had no idea where Mr Baumann was and that he, “might take a jog down to Peter’s place”. Ms Seneviratne asked why he would do that when she had just been there and he replied, “yes, I might still take [a] jog down there anyway”.

89. Ms Seneviratne stated that she then drove home and read the letter she had taken. She didn’t keep it, but recalled it said something to the following effect: Dear Peter, I have finally told Oliver about us. I have told him how much I love you and that I want to be with you. I have also told him that I want to sell the house but (word was unreadable) was giving him a hard time about selling the house.

90. Ms Seneviratne could not remember the entire letter but recalled that it said, “how much he cares for Peter how much he wants to be with him”. Ms Seneviratne stated that the letter was signed either “Dillian” or “William”.

91. According to Ms Seneviratne, she returned to the Cross Street premises the next day (a Saturday) with her sister, Dilania Seneviratne. They arrived at around 9:00am to 10:00am and she noticed that Mr Baumann’s room was in the same condition as it had been the previous day. Ms Senevirante knocked on the door of Mr Baumann’s neighbour and enquired as to his whereabouts. Mr Baumann’s neighbour did not know where Mr Baumann was but heard him arguing with a girl on the phone and stated that Mr Baumann had “burnt a cushion”. 103

92. Ms Seneviratne’s recollection as set out in the above paragraphs is not supported by the evidence provided to the NSWPF by Mr Pears on 13 April 2007, or Dilania Seneviratne on 14 June 2007. 104 However, Dilania Seneviratne does remember “standing at the door” of a “very messy” room when she was around 16 years old.

93. According to Ms Seneviratne, after “a few weeks” she notified Mr Baumann’s “landlady Ruth BAVAMDYUM” (presumably Ms Binney) by telephoning her at her home in Epping, Sydney. Ms Binney told her she had not seen Mr Baumann since he paid his rent money “about two weeks before he went missing”. Ms Binney also told her that she had “reported the matter to Waverley or Bondi Police Stations”. According to Ms Seneviratne, Ms Binney told her that the NSWPF had taken “his passport and wallet and personal papers”. Other items belonging to Mr Baumann were placed in storage at her house in Epping.

94. According to an unsigned statement provided to the police by Ms Binney in 1993, Ms Binney, at some time in “October 1983”, became aware that Mr Baumann was missing. She received a telephone call from Ms Seneviratne who informed her that she had been on the phone with Mr Baumann when the line went dead and that she had been to his flat and found “the chair overturned and the door open”. Ms Binney stated she went over to the flat “the next day”. 106

95. According to Ms Binney, upon looking through his room, she saw “the armchair turned over, his jacket was on the bed and it looked as though he was packing his clothes into plastic bags…and his bed pillow was lying in the shower half burnt”. Ms Binney also noticed the word ‘AIDS’ had been written on a mirror.107 As noted above at paragraph [7], there is evidence to suggest that Ms Seneviratne may also have seen the word ‘AIDS’ written on the mirror. After Ms Binney inspected Mr Baumann’s flat, she stated that she “rang the Police at WAVERLEY and the uniformed Police arrived and they took a photograph from his identity card.”108

96. On 29 November 1983, the NSWPF prepared a missing person report in relation to Mr Baumann that records that Ms Binney was the informant. 109

97. According to an unsigned statement provided to the police by Mr Smyth in 1993, Mr Smyth last saw Mr Baumann “on a Sunday, it was in Summer in 1983” when he visited him at the Cross Street premises. 110 Although the police appear to have deduced that this date was 23 October 1983, it is also possible that this date was 30 October 1983, for reasons explained below. Mr Smyth stated that Mr Baumann was meant to see him the next day, which was a Monday, but that he did not show up. Mr Smyth appears to have been the last person to see Mr Baumann before he disappeared. 111

98. On the Tuesday or Wednesday after Mr Baumann failed to meet Mr Smyth when he was meant to, Mr Smyth stated that he became worried and attended the Cross Street premises. He observed that the front door of Mr Baumann’s flat was open, his bed had not been made but that “his guitar and everything was intact”. Mr Smyth asked a neighbour (an Australian man in his late 50s) for a key to Mr Baumann’s flat so that he could lock it. The neighbour said he would lock it and Mr Smyth asked him to inform Mr Baumann that “Allan” had been around.112

99. According to Mr Smyth, “later that week” he received a telephone call from “a man at the A.B.C. asking if I had seen Peter”. Mr Smyth told then he “hadn’t seen him since that last Sunday”. Mr Smyth said he “might have” gone back to Mr Baumann’s flat the following Friday or on the weekend. Mr Smyth stated that over the next week, he started to worry because he“knew of the demand for money” and that the notion of ‘Cooper Pedy’ was stuck in his mind. Mr Smyth was also unsure about why Mr Baumann left his expensive guitar behind.113

100. Mr Smyth also stated that a “man and lady” attended his residence a “couple of weeks” after Mr Baumann’s disappearance and that occurred at around 8:30pm. He stated that these two people asked about Mr Baumann’s whereabouts and told him that they were worried. Mr Smyth described them as “both white and he was a bit overweight and the girl was medium build with fair [hair]”. Mr Smyth says that he was suspicious because Mr Baumann never mentioned these friends but did not go to police as he had his “own problems at the time”. He further stated that he did not make any enquiries about Mr Baumann until he was contacted by police.114 There is a chance that Mr Smyth is referring to the visit to the Artlett Street property by Ms Seneviratne and Mr Pears but Mr Smyth’s description of the woman that attended his property does not match the description of Ms Seneviratne provided by her cousin Mr Pears, who described her as having “dark skin, wavy long black hair, dark eyes, thin build”. 115

101. At some stage during the course of the police investigation, the police seem to have concluded that the conversation between Ms Seneviratne and Mr Baumann occurred on or around 26 October 1983, and that Mr Baumann has not been seen or heard from since this time. However, there are several issues arising out of the evidence described in the above paragraphs that are worth considering when trying to establish what happened prior to Mr Baumann’s disappearance, and when it happened.

102. First, if Mr Smyth’s statement is accurate and he last saw Mr Baumann on a Sunday (and he was contacted by the ABC “later” the following week), it would appear likely that Mr Smyth saw Mr Baumann on Sunday, 30 October 1983, and that he was supposed to meet with Mr Baumann on Monday, 31 October 1983. The telephone call with the ABC would then have occurred sometime in early November.

103. In a file note prepared by Mr Gover dated 9 November 1983, Mr Gover refers to a call from “William” of “artell(?) St Edgecliff stating that he did not know the whereabouts of Peter”. Mr Smyth could be the “William” who is recorded as contacting Mr Gover on Wednesday 9 November 1983, which raises the possibility that Mr Smyth’s meeting was as late as Sunday 6 November 1983, although it is equally or perhaps more likely that Mr Smyth’s recollection may have somewhat telescoped, and his conversation with the person from ABC may not have been the week immediately after the Sunday.

104. Second, the above is consistent with the contemporaneous evidence that suggests Mr Gover sought to locate Mr Baumann on Thursday, 3 November 1983 and again on Friday 4 November 1983. 116

105. Third, the above is also consistent with some of the non-contemporaneous evidence contained in Mr Smyth’s statement and Ms Seneviratne’s statement. Mr Smyth states that the person from the ABC told him that Mr Baumann’s job would be kept open for two weeks, and it is recorded that by 9 November 1983, Mr Gover was thinking the job would need to be terminated that day.117 Ms Seneviratne states that she spoke to Mr Baumann “one Friday” and contacted Ms Binney “a few weeks later”. It is possible this date was Friday, 4 November 1983 and not Friday, 28 October 1983. Mr Gover prepared a file note that indicated that “Sharmalee” contacted him on 7 November 1983 (i.e. the following Monday) and was going to see him the following day.

106. However, there is still some conflict between Ms Seneviratne’s evidence that she spoke to Mr Baumann “one Friday” and went to Mr Smyth’s house that same day, and the visit that Mr Smyth recalls as occurring “around a couple of weeks later”, after Mr Baumann disappeared. There are several possible explanations for this, including possible telescoping of memory and/or that Ms Seneviratne saw Mr Keasberry rather than Mr Smyth, and that the visit Mr Smyth recalls from a white woman with fair hair was not Ms Seneviratne.

107. Fourth, as noted above, the relevant dates and days of the week may not be reliable given the passage of time before Ms Seneviratne and Mr Smyth prepared their first statement; both statements appear to contain a certain level of telescoping and/or imprecision as to the relevant dates. Mr Gover’s record appears to be contemporaneous and is the most reliable record as far as it goes. On the basis of the above matters, however, it is not clear how the NSWPF arrived at the conclusion that Mr Baumann disappeared on 26 October 1983 or why Deputy State Coroner Milovanovich was informed that Mr Baumann disappeared on or around this date.

Events after October 1983

108. According to Ms Seneviratne, in 1992, and just after speaking to the police about Mr Baumann’s disappearance, she made various enquiries and obtained the contact number for Mr Smyth. At that time, she telephoned him and asked if he knew where Mr Baumann was. Mr Smyth said: “No sorry love I have’nt [sic] heard from him for years”. Ms Seneviratne again telephoned that number and asked to speak to ‘Dillian’. She states that the following conversation ensued: Unknown male: “Speaking” Ms Seneviratne: “Do you have any idea as to where Peter is?” Unknown male: “No I don’t know where he is, who’s calling?” Ms Seneviratne: “I know what was written in the letter. I know that you were going to leave Oliver for Peter.” Unknown male: [becomes upset] “I’m in the security business. I’ll find out who you are.”

109. Ms Seneviratne then hung up and made no further enquiries after that incident.118 Ms Seneviratne’s separate reference to speaking to Mr Smyth and then speaking to a person who answered to ‘Dillian’ suggests she did not think they were the same voice.

110. The evidence available in 1993 indicated that, at that time, both Mr Smyth and Mr Keasberry had some connection with the security industry, in that Mr Keasberry held a security licence and Mr Smyth was the director of a security firm named Watchguard Pty Ltd.119

111. There is other evidence before this Inquiry that suggests that prior to finalising his statement, on 15 October 1993, Mr Smyth telephoned police. NSWPF records indicate that Mr Smyth told police that Mr Baumann was probably accidentally killed by unknown persons and that his body was “probably dumped in a bush”. The records further indicate that Mr Smyth told police he “wished to speak privately of [the] matter in the future”. There is nothing to suggest that police ever followed up Mr Smyth or acted on his desire to speak privately to them.

112. Furthermore, at some stage during the police investigation, Mr Smyth told police not to speak to Mr Keasberry as he was exclusively heterosexual, “highly moral” and had very little contact with Mr Baumann.121 The NSWPF records also contain the following handwritten note under information about Mr Keasberry: Shares house with SMYTH and was sharing house at the time of relationship with BAUMANN financial arrangement (both equal partners in house at Edgecliff at time of disappearance.) SMYTH denies that OLIVER homosexual, describes him as very straight, conservative highly moral person ? does not want police to interview OLIVER. 122

113. The Artlett Street property was later sold (in the mid-1980s). 123 There is no evidence to suggest that any person other than Mr Smyth or Mr Keasberry lived there, although this line of enquiry does not appear to have been exhausted by police. There is also evidence that Mr Smyth leased an adjacent property to the Artlett Street residence, which had an in-ground swimming pool, and that parties were held on this property from time to time. 124 It appears that swimming pool was filled in prior to the sale of the property in the mid-1980s.

114. A number of other developments happened in relation to this case in 2007 when the police took steps to further the investigation into Mr Baumann’s disappearance. At this time, police established that Mr Smyth was still living with Mr Keasberry but they had relocated to Western Australia. 125 Upon speaking to the police in 2007, Mr Smyth denied ever saying that Mr Baumann may have been accidentally killed and dumped in a bush.126

115. Ms Seneviratne also prepared a second statement that was dated 27 April 2007. In that statement she recalled an occasion in 1996 where a brown Valiant drove up and down her street. She watched the vehicle for a period and then saw a man standing under a tree across the road. She thought the man looked like Mr Baumann and had similar physical features. She saw the man approach her house and quickly closed the door before contacting her neighbour. The man walked back under the tree across the road.127

116. It is submitted that the above evidence raises many questions that the NSWPF did not seek to explore. Furthermore, and to the extent that there are inconsistencies in the above evidence, it appears that no steps were taken in 1993 to 1994 to reconcile these inconsistencies with each other or to determine whether the evidence provided by each of the witnesses was reliable or not. Some steps were taken in 2007 to ascertain the reliability of the evidence provided by witnesses in 1993but these steps were incomplete and rendered more difficult due to the passage of time.

Police Investigation 1983 to 1991

117. As noted above, Mr Baumann’s disappearance was reported to the NSWPF in 1983. Although there is evidence to indicate that the NSWPF attended the Cross Street premises and obtained some personal information about Mr Baumann, no contemporaneous record of any police investigation into Mr Baumann’s disappearance at that time has been produced to this Inquiry. Although there is evidence to suggest that “all the Occ Pads and T.P. Messages for 1983 were accidentally burnt”, 129 that does not explain the absence of any records of any investigative steps at all. Furthermore, there is evidence before this Inquiry that this matter was “not investigated until 1993”. 130 It is not known why Mr Baumann’s disappearance was not investigated at the time (see submissions at [19]-[22] above).

118. On 27 September 1989, Waverley Police Station conducted some routine checks for people listed as missing “within the Waverley patrol”. No reference for Mr Baumann was found.

1992 to 1994

119. From around 1992 the matter was investigated by SC Gribble from the Missing Person’s Unit. SC Emery also appears to have been involved in the investigation from around this time.132

120. In 1992, the NSWPF conducted various checks to see whether Mr Baumann could be located, but with no relevant results.133

121. On 27 August 1993, the NSWPF received information from Interpol in relation to Mr Baumann.

122. On 3 September 1993, a request was submitted to the Bavarian State Police via Interpol requesting that Anna Baumann, Mr Baumann’s sister, be interviewed to obtain particular information.134

123. On 9 September 1993, SC Gribble submitted a report to the Department of Immigration in relation a Japanese national, ‘Hyuma Hoshi’, who was identified as a possible witness to Mr Baumann’s disappearance.

124. On 26 November 1993, the NSWPF wrote to the ABC to request their assistance in obtaining the employment records of Mr Baumann and the contact details of Mr “Govey” (presumably referring to Mr Gover).

125. In 1993, “a number of statements were obtained from next of kin and witnesses”. 136 These statements included:

a. A statement of Ms Seneviratne dated 26 August 1993;

b. A statement from Mr Smyth dated 16 November 1993;

c. A statement of Ms Binney dated 16 November 1993; and

d. A statement of Ms Foster dated 14 September 1994.

126. In 1994, Mr Baumann’s matter was briefly transferred to Waverley Police Station before being almost immediately transferred back to the MPU. 137

127. On 26 May 1994, the NSWPF spoke with Mr Baumann’s brother and sister(Anna and Franz Baumann) who had arrived in Australia from Germany the previous day . At this meeting the NSWPF “spoke… at length” and Mr Baumann’s siblings were “informed of the possibilities concerning their missing brother”. 138 As at this date, Mr Baumann’s family had only recently been informed there had been a missing persons report made about their son and brother.

128. On 30 May 1994, Mr Baumann’s brother and sister met with Ms Foster at the MPU. NSWPF records indicate that the “Baumanns appeared to be distressed as to the lack of Police action taken

129. There is evidence to suggest that by June 1994, there was tension between SC Gribble and SC Emery about the NSWPF response to Mr Baumann’s disappearance. 141 As noted above, SC Gribble appears to have been frustrated or angry that not enough was being done and that Mr Baumann’s family had not been told earlier about the disappearance. SC Emery appears to have been opposed to investigating the matter further. Without full records, it is impossible to draw any definitive conclusions about what appears to be conflict within the NSWPF about this matter.

1999 to 2002

130. on 11 November 1999, the NSWPF received a request from Mr Baumann’s siblings, through Interpol, that further attempts be made to try and find him.

131. In 2001, certain routine checks were made to try to ascertain Mr Baumann’s whereabouts. 143 On 11 September 2001, a fax was sent by the MPU to Mr Baumann’s family providing them with an update and informing them of a program whereby the MPU obtained DNA samples from the families of long term missing persons.144 There was subsequent correspondence through Interpol about arranging a DNA sample from Mr Baumann’s parents.145

132. In 2002, Operation Utica was instituted with a view to investigating a number of missing persons matters within the Penrith Local Area Command. Mr Baumann’s matter seemingly fell within the purview of Operation Utica. Notwithstanding, it appears that no investigative steps were taken in furtherance of Mr Baumann’s matter. Rather, an attempt was made to reassign the matter to the Eastern Suburbs Local Area Command. Separate to Operation Utica, the MPU made checks with financial institutions in respect of Mr Baumann during this time.146 2005 to 2009 133. On 9 November 2005, Detective Sergeant (DS) Darren Smith was appointed as the Officer In Charge. 147 DS Smith undertook the following investigative steps:

a. On 17 November 2005, DS Smith made enquiries with the Coroners Court to relation to whether they held any records in relation to Mr Baumann but they did not.

b. On 17 November 2005, DS Smith contacted the MPU to obtain the investigative file in relation to Mr Baumann and “all related paperwork”. On 7 December 2005, DS Smith received the requested items and he recorded that it consisted of “the statements obtained by Police investigating BAUMANN’S disappearance and enquiries made by Police back in 1993, 10 years after he was reported missing”.

c. On 5 April 2006, DS Smith sought to have Mr Baumann’s case allocated to the “detective’s office at Eastern Suburbs” for further investigation.150 On 7 March 2007, the case was allocated to DS Smith when he transferred to the Eastern Suburbs LAC.

d. In April 2007, DS Smith contacted and obtained statements from John Pauperis (Ms Foster’s boyfriend at the time Mr Baumann disappeared), and Hamish Pears. 152 The statement of Mr Pauperis is dated 11 April 2007 and the statement of Mr Pears is dated 13 April 2007.

e. Also in April 2007, DS Smith contacted Mr Smyth and Mr Keasberry and recorded that Mr Smyth’s “memory may be failing him” and that Mr Keasberry denied ever knowing Mr Baumann. 153 DS Smith was unable to contact Ms Foster.154

f. Also in April 2007, DS Smith contacted Ms Seneviratne who confirmed she had no further information than what she provided the NSWPF in 1993 save that she thought she had seen Mr Baumann in 1996 but she did not report this to the police.155 A further statement form Ms Seneviratne was subsequently obtained which is dated 27 July 2007.

g. In May 2008, DS Smith requested information from Medicare, telecommunications companies, Centrelink, the NSW Electoral Commission and the Department of Immigration and Citizenship.

h. Also in May 2008, DS Smith made enquiries within the NSWPF about whether any unidentified persons had been located that matched Mr Baumann’s description or whether two items of property (Mr Baumann’s guitar and carving knife) were handed to Parramatta Police Station on 13 September 1993 by SC Gribble. No relevant results appear to have been obtained 134. In 2006, the Eastern Suburbs Local Area Command requested the assistance of the NSWPF Homicide Squad. This request for assistance was denied pending any coronial findings being made as to the disappearance of Mr Baumann.158

135. On 8 March 2007, Strike Force Blissett was formed to investigate the circumstances surrounding the 1983 disappearance of Mr Baumann.

136. Between 26 May 2008 and 3 June 2008, the investigation into Mr Baumann’s disappearance was transferred to Plain Clothes Senior Constable (PC SC) Simon Field.160 PC SC Field “made a number of name checks utilising the Police and RTA systems” and “received information…. That a fresh search of the ‘Unidentified Bodies’ data base had failed to locate a match for BAUMANN”.

137. On 25 April 2008, PC SC Field completed the P79A. PC SC Field concluded that: It is apparent that BAUMANN is missing believed deceased. BAUMANN has not left the country under his original passport and is believed to still be in the country. Through the various witness statement it may appear that BAUMANN has met with foul play with the varied and bizarre relationships he held whilst in Australia. Although it can not be discounted that BAUMANN, using an alias, has simply changed his name to avoid detection, so that he may remain within Australia illegally, as is stated by witnesses, that he had held grave fears of returning to Germany. Due to the length of time involved in this investigation, police have little evidence at this stage to assist in the disappearance of BAUMANN.

2011 onwards

138. In 2011, 2014 and 2016 to 2017, several discrete investigations were made regarding Mr Baumann’s dental records and potential links with an unidentified body in the Northern Territory. There also appears to have been some liaison between the MPU and the Eastern Suburbs Local Area Command regarding outstanding requisitions to be progressed.

Hypotheses as to manner and cause of Mr Baumann’s death

139. As noted above, there are a number of available hypotheses as to the manner and cause of Mr Baumann’s disappearance and death.

140. First, Mr Baumann may still be alive and living under an assumed identity. This hypothesis was considered likely by SC Emery in 1994163 and possible by SC Gribble.164 The fact that Mr Baumann used other identities or aliases including “Peter Moltzen” and “Peter Ann” may support this theory. Some more support for this hypothesis may be drawn from the fact that Mr Baumann was reluctant to return to Germany for compulsory military service. However, the evidence on this point is equivocal and he had already obtained permanent residency. It is also noted that all proof of life checks have returned unsuccessful results since the police began making them in 1992.

141. Accordingly, although it is highly doubtful that Mr Baumann is still alive, this hypothesis cannot be completely ruled out.

142. Second, Mr Baumann may have died by suicide. This hypothesis was also considered likely by SC Emery in 1994, 165 although unlikely by SC Gribble. 166 Although there are no medical records before the Inquiry concerning Mr Baumann’s medical history, some witnesses have given evidence about Mr Baumann’s depression and a marked decline in his mental health in around March 1982. During this period, he was said to have become increasingly paranoid and aggressive, which may have been due to Mr Baumann’s belief that persons were conspiring to have him deported.167 There is also evidence that in the days or weeks preceding his disappearance, Mr Baumann was absent from work, apparently due to influenza and nausea. Furthermore, it is alleged that Mr Baumann stated words to the effect of, “I would rather die than return to Germany”. 168

143. However, any evidence said to support the hypothesis that Mr Baumann died by suicide must be considered against other evidence, including that that Mr Baumann had successfully obtained permanent residency in April 1983 and secured ongoing employment as a Sound Library Assistant at the ABC.

144. Third, Mr Baumann’s death may have been caused by associates of Ms Foster. Support for this hypothesis can be obtained from evidence that Mr Smyth provided in his statement to police although it is not corroborated in any substantive way in any other evidence before this Inquiry.

145. Mr Smyth gave evidence that Mr Baumann paid Ms Foster in exchange for her getting married to him, and/or that she was a sex worker. According to Mr Smyth, Mr Baumann told him that persons described as Ms Foster’s “protectors” had asked for “another $30,000”. They told Mr Baumann that they knew where he lived, and Mr Smyth formed the impression that they were blackmailing Mr Baumann. Although Mr Smyth did not know the precise nature of the threats directed at Mr Baumann, he thought they were of a physical nature. In a subsequent statement to police, Mr Smyth stated that he believed Mr Baumann was killed after a “situation got out of hand” and that his body had been disposed of in the bush.

146. However, it does not appear this hypothesis was pursued by the NSWPF in any considered or systematic way. Whilst a statement was obtained from Ms Foster in 1993, it did not address the allegations identified above. Further, it appears that no efforts were made to identify Ms Foster’s “protectors” or whether, in fact, any threats were made to Mr Baumann. To that end, Ms Foster denies that a lump sum was ever paid to her, and attributes the weekly payment to Mr Baumann covering her loss of the “dole” upon their marriage.

147. Fourth, Mr Baumann may have been killed as a result of his relationship with Mr Smyth and/or Mr Smyth’s partner, Mr Keasberry. This was also a hypothesis contemplated by investigating police.

148. From around December 1981 to the time of his disappearance, Mr Smyth and Mr Baumann were in a relationship. However, the nature of the relationship between Mr Smyth and Mr Keasberry is less clear. Mr Smyth and Mr Keasberry resided together in Artlett Street, Edgecliff, and indeed, they continued to reside together for many years after this. However, there is conflicting evidence as to Mr Keasberry’s level of involvement with (or knowledge of) Mr Baumann, at least around the time of his disappearance.

149. The evidence provided by Ms Seneviratne that she found a letter in Mr Baumann’s mailbox that was authored by someone called a “William” or “Dillian” who lived at the Artlett Street property was going to leave “Oliver” for Mr Baumann, may suggest Mr Smyth was in fact the “William” or “Dillian” who was in a relationship with Mr Keasberry. The contemporaneous file note by Mr Gover also records that he received a call from someone by the name of “William” who lived at the Artlett Street property (in his file note of this call Mr Gover put the name ‘William’ in inverted commas). That person told Mr Gover that they did not know the whereabouts of Mr Baumann. 169 It is also possible that the name ‘Allan’, when handwritten, could look like ‘William’ or ‘Dillian’, and when spoken, could sound like ‘William’. In this respect, it is relevant that Mr Smyth recalls speaking to a man from the ABC about Mr Baumann’s disappearance although his recollection was that a man from the ABC called him. 170

150. It could also be considered suspicious that Mr Smyth did not want police to speak to Mr Keasberry about Mr Baumann’s disappearance and the contents of the letter itself and the reference to difficulties in ‘selling the property’ may align with Mr Smyth and Mr Keasberry jointly owning the Edgecliff property.

151. A curious feature of the eventual sale of the Artlett Street property was the existence of a plastic swimming pool which was built on land adjacent to the property that was leased by Mr Smyth. The pool was filled prior to the Artlett Street property being sold in December 1987.

152. Furthermore, Mr Baumann’s family are of the view that Mr Baumann’s disappearance is linked to his “homosexual contacts” and their impression that Mr Keasberry was very jealous that Mr Baumann “intruded into this community”.

153. There is no record of NSWPF interviewing Mr Keasberry at any stage of their investigations, nor was this theory put to Mr Smyth or explored in any real way with any of the witnesses.

154. The evidence available to the Inquiry does not permit any positive conclusion about this theory.

155. Fifth, Mr Baumann was killed in a gay hate or gay bias motivated homicide. The evidence supporting this hypothesis is outlined above at paragraph [15].

Submissions as to bias

156. The Inquiry’s ability to assess whether any LGBTIQ bias was involved in Mr Baumann’s death is compromised by the fact that it is not apparent that Mr Baumann died as a result of foul play, and if so, who was involved in his death and why.

157. Nonetheless, there is evidence that suggests that Mr Baumann may have been a victim of foul play. Indeed, at all relevant times the NSWPF appeared to consider Mr Baumann’s disappearance as suspicious. For example, for the purpose of the coronial proceedings, PC SC Field furnished a statement in his capacity as Officer in Charge where he stated that “through the various witness statements it may appear that [Mr Baumann] was met with foul play” noting the “varied and bizarre relationships” he had whilst in Australia.

158. There are a limited number of factors that suggest his death may have occurred in circumstances of LGBTIQ bias, namely that Mr Baumann was a gay or bisexual man, that he disappeared in suspicious circumstances, and that the word ‘AIDS’ was written on a mirror at the Cross Street premises. As observed above, it is important to note that bias in relation to HIV-status does not necessarily indicate LGBTIQ bias, although there is significant potential for overlap, especially considering social attitudes to HIV and homosexuality at the time.

159. Although it is submitted that there is sufficient evidence to find that Mr Baumann is deceased, it is submitted that this evidence is insufficient to give rise to any positive finding that Mr Baumann’s death involved LGBTIQ hate or bias. In addition, there remains several reasonable alternative hypotheses about how Mr Baumann died, as identified above at paragraphs [139] to [155]. Several of those alternative hypotheses are less consistent with LGBTIQ hate or bias.

160. As indicated at [28] above, even if Mr Baumann was not the victim of a hate or bias crime, it is possible that the failure of the police to investigate the disappearance thoroughly in 1983 was influenced by bias. However, given the absence of adequate police records, no affirmative conclusion can be drawn in this regard.

Submissions as to manner and cause of death

161. It is submitted that the Inquiry should make a finding that is consistent with the finding of Deputy State Coroner Milovanovich, save that the finding of the Inquiry should reflect the evidence about the likely date that Mr Baumann went missing, as explained above at paragraph [8]: Peter Baumann is deceased. I find that he died some time on or after 27 October 1983. As to the precise date of death, place of death or manner and cause of death from the available evidence I am unable to say.

Submissions as to recommendations

162. Counsel Assisting proposes the following further recommendation be made:

a. That the NSWPF obtain a physical reference sample from Mr Baumann’s sister, Anna-Christa Baumann-Serr, for the purposes of ensuring that an autosomal DNA profile is available for searching against DNA profiled from unidentified human remains on the national DNA database.

b. That a recommendation should be made to the Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages to correct the Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages pursuant to s 45(1)(b) of the Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1995, such that Mr Baumann’s date of death is recorded as “on or after 27 October 1983”.

163. Counsel Assisting understands that Ms Baumann consents to the above recommendation being made.

164. Counsel Assisting may make submissions as to further possible recommendations in confidential submissions.

James Emmett SC Senior Counsel Assisting

Meg O’Brien Counsel Assisting

A series of failures by police to follow up key recommendations could have led to breakthroughs in multiple cold cases while glaring errors hindered crucial lines of inquiry, an inquiry has been told.

The blunders were laid bare during a Special Commission of Inquiry into suspected gay hate deaths in Sydney, part of hundreds of unsolved homicides languishing on file.

Unsolved homicide squad Detective Chief Inspector David Laidlaw conceded his team had no record of many of the cold cases being examined and had made no communication with the hate crimes unit over the course of the hearing.

The inquiry heard a 2005 recommendation to obtain a DNA sample from a person of interest in the unsolved murder of William Dutfield was ignored.

By the time police eventually tried to obtain a sample in 2008 the person had died.

Other documents tendered to the court showed a series of inaccuracies and “obvious errors”.

Written evidence relating to the case of Peter Baumann – a man who disappeared from Sydney in the 90s with his body never to be recovered – made references to post-mortem results.

Det Chief Insp Laidlaw conceded the evidence was “just plain wrong”.

Counsel Assisting James Emmett SC said the inquiry had identified a number of cases in which lines of inquiry were identified that were “either not implemented or not implemented for a decade or more”.

In another startling admission, Det Chief Insp Laidlaw said his team “quite possibly” did not look at any cases at all between 1970 and 2009 and agreed he had “absolutely no idea as to the dimension of the problem”.

The inquiry was earlier told that out of more than 400 cold cases, 201 were identified for reinvestigation.

Det Chief Insp Laidlaw was unable to say how these cases were selected, where the list could be found or whether anyone had been tasked with the reinvestigations.

“Did you just pick them at random?” Mr Emmett asked.

Only 76 cases were found to have been reviewed between 2009 and 2017 despite a team of 38 full-time officers working within the NSW unsolved homicide team.

Mr Emmett said at the current rate it would take the detectives about 50 years to review all cases on file.

“So will it be, what, 40 to 50 years on your current track to review them all?” he asked the chief inspector and 38-year veteran of the force.

Commissioner John Sackar earlier asked Det Chief Insp Laidlaw why an urgent audit of all unsolved cases had not taken place.

“These are all people’s lives and people’s family’s lives,” Justice Sackar said.

“Am I missing something, or do I detect that the police as an institution don’t rate unsolved homicide too highly in terms of priorities?”

The inquiry was told that before 2004 there was no system in place for the management or review of unsolved homicides.

Despite relying on a tracking file as a “live document” to keep recording unsolved homicides and suspicious deaths, the inquiry was shown that the last matter on file was from August 2016.

Det Chief Insp Laidlaw said the official record management system used by his team since it was established in 2004 was still a work in progress when asked why no data had been recorded for the past seven years.

The inquiry was told at least six high-profile suspected gay hate cold cases currently being examined by the commission were not recorded on tracking file.

Det Chief Insp Laidlaw was unable to explain why the case details of William Allen, Robert Malcolm, James Meek, Richard Slater, William Rooney and Carl Stockton – all killed in brutal assaults during the 1990s – were seemingly absent from the squad’s official working document.